Events to mark the 300th anniversary of David Garrick’s birth have been taking place all year. Born in 1717, Garrick burst onto the London stage in 1841 in the role of Richard III. The Museum of London has held an exhibition relating to him. A man of many talents, he combined the functions of writer, actor and theatre manager and became the most famous person to be associated with the theatre for the rest of his lifetime, and long beyond his death.

He was a talented writer of plays but it’s as an actor that he is best remembered. Garrick knew that making his image widely known, particularly showing him in character, would help to make him famous and increase his audiences. He was also a collector and The Garrick Club in London’s website notes:

“There are over 250 portraits of Garrick, in private and stage character, original and engraved, more than those of any other actor, and exceeded in the “Catalogue of Engraved British Portraits in The British Museum” only by those of Queen Victoria. The Garrick Club holds some 21 of them, along with his life-mask, chair, silver and other memorabilia. Important caches of material and documents about him are in the Garrick Club Library, the British Library, the Folger Shakespeare Library and the Victoria and Albert Museum. When the British Museum was established in the latter half of the eighteenth century, Garrick’s fine collection of old plays formed the nucleus of its library.”

On the subject of those 250 portraits, Dr Johnson’s House in London will continue to mark Garrick’s tercentenary into 2018 with a lecture by Sheila O’Connell entitled Prints of Me: portraits of Garrick on 31 January at 7pm. Sheila is the curatorial advisor to Dr Johnson’s curator of prints, formerly working at the British Museum.

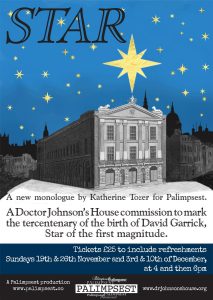

Garrick’s stage career is also being celebrated at Dr Johnson’s House where, on the 26 November, 3 and 10 December they are staging Star, a monologue by the Palimpsest company, featuring actor Nick Barber as Garrick. It’s set in September 1747, “as a wave of ‘Garrick Fever’ hits London for the opening of the Drury Lane Theatre under the actor’s management. With the reputation of theatre at an all-time low, Garrick sets out to make himself rich and his profession acceptable. With a Prologue to the new season written by Samuel Johnson, Garrick promises to throw new light on elocution and action, banish ranting and bombast and to restore simplicity and humour to the British Stage.”

Garrick’s stage career is also being celebrated at Dr Johnson’s House where, on the 26 November, 3 and 10 December they are staging Star, a monologue by the Palimpsest company, featuring actor Nick Barber as Garrick. It’s set in September 1747, “as a wave of ‘Garrick Fever’ hits London for the opening of the Drury Lane Theatre under the actor’s management. With the reputation of theatre at an all-time low, Garrick sets out to make himself rich and his profession acceptable. With a Prologue to the new season written by Samuel Johnson, Garrick promises to throw new light on elocution and action, banish ranting and bombast and to restore simplicity and humour to the British Stage.”

I’ve recently been re-reading Vanessa Cunningham’s book Shakespeare and Garrick that concentrates on Garrick’s literary career. Garrick wrote a number of his own plays and the Ode that formed the main event of his Shakespeare Jubilee in Stratford-upon-Avon. He is often given credit for restoring Shakespeare’s texts to the stage after many decades when they had been plundered in order to create crowd-pleasing entertainments. Vanessa Cunningham examines this theory, looking in great detail at Garrick’s versions and how they compare with both Shakespeare’s original and other stage versions.

David Garrick had a very long relationship with Shakespeare’s tragedy King Lear. He first played the part in 1742, less than a year after he had first performed in London and aged only 25. At this time audiences were used to seeing the version put together by Nahum Tate, best known for its un-Shakespearean happy ending. Tate removed words and phrases deemed offensive, invented a romance between Cordelia and Edgar, and omitted the Fool. Early in his career Garrick would have used this adaptation more or less as written. Over his career Garrick was to play Lear eighty-five times, the last time in 1776 just before his retirement from the stage. He therefore had plenty of opportunity to restore Shakespeare’s text, and Vanessa Cunningham charts, as far as it is possible, how he changed it. In fact by the 1770s, although Garrick had reinstated 255 lines of Shakespeare he had not put back the tragic ending of the play, nor had the Fool made an appearance.

We shouldn’t judge Garrick harshly for not doing more. Audiences knew and loved the play as Tate had adapted it, and would have been outraged by major changes. Vanessa Cunningham also points out that Garrick’s theatre was very much an actor’s theatre. As well as spectacular entertainment they wanted their leading actors to dominate the plays they were in, and to provoke emotional responses. Garrick was enormously successful at appealing to his audiences.

The theatre for which Shakespeare and his contemporaries wrote relied on the skill of the writer to conjure up compelling characters and situations. Although most Shakespeare performances stay close to what Shakespeare wrote, one only has to take a look at a few modern prompt books to see how many lines are cut, and how many words are changed. The gap between stage and page is smaller than it once was, but still remains.