It’s 60 years ago, in April 1959, that one of the most important events in the history of the theatre in Stratford-upon-Avon took place. Paul Robeson, the great American singer and actor, became the first black Othello in Shakespeare’s town in the twentieth century.

Recently Professor Tony Howard spoke about Robeson’s Othellos to the Shakespeare Club in Stratford-upon-Avon. During his talk he revealed how this event almost didn’t happen at all because Robeson had been taken ill while he was in Moscow. The theatre’s management were standing by to announce another black actor, William Marshall, in the role, but the anticipation was so intense that desperate efforts were made to allow him time to recover. The rehearsals began without him, with understudy Julian Glover taking his place for the first two weeks. A weakened, aging Robeson arrived to begin a month’s rehearsals on 12 March. If his illness affected his performance it didn’t matter. Robeson was a myth, a hero, and at the end of the first performance the audience would not stop cheering.

It’s rare for an actor to get several bites at any Shakespearean cherry, but Robeson was extraordinary. No actor has been associated so profoundly with any Shakespearean part as he was with Othello. There were three productions, over 29 years: at the Savoy Theatre in 1930, on Broadway and on US tour in 1943-45, and in 1959 at the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre in Stratford. Robeson’s portrayals, and the productions themselves, charted twentieth century developments in race relations on both sides of the Atlantic.

When he came to England in 1930 he was already a star, both as an actor and a singer. He continued to sing “Ol’ Man River” from Showboat, easily his most famous song, throughout his career, altering the words to fit the event and the political mood. Robeson wanted this production to make a political statement. Both he and his Othello were insecure outsiders in an unfamiliar world. He doted on and was enraptured by his Desdemona, Peggy Ashcroft, both on and off the stage. We know it was controversial to see a black man embrace a white woman in public at the time, but Professor Howard revealed, more shockingly, that some people walked out because Indians and Africans were in the audience.

Even though the production was successful Robeson felt he needed more experience to perform in Shakespeare. A revival was planned but in the event it took until 1943, during World War 2. In this production Robeson and Othello dominated the stage. The world was changing and Iago was visibly fascist and racist. It had a record-breaking run and was declared a “national victory for progress”.

By 1959 the world had changed again. Robeson had survived the McCarthy era despite being a political activist, but his international stardom did not give him the right to travel. His passport had been restored to him only in 1958. He had not even been allowed to go to Canada, several times performing on the border while Canadians listened from the other side. Now in his sixties Robeson performed Othello as an older man, weakening, surrounded by youth, but still with mythical status. Another American, Sam Wanamaker, was cast as Iago, a method actor from a different generation. To his great credit Robeson and he held improvisation sessions together. At last, too, Robeson found in Tony Robertson a director who helped him to understand the words, not just make them sound beautiful. Robeson’s performance might not have been perfect but it was totally committed and he saw it as the climax of his career.

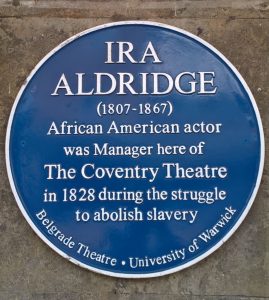

In my first paragraph I noted that Robeson was the first black Othello in Stratford in the twentieth century, not ever. In 1851 another black American, Ira Aldridge, played the part in the theatre that then stood in Chapel Lane. Paul Robeson had been aware of Aldridge for years before he came to Stratford. In 1930 Robeson arranged for a material about Aldridge, including playbills, to be displayed at the Savoy Theatre. He actively pursued connections with Aldridge, rehearsing with is surviving daughter. An almost-forgotten man for many years, Aldridge is now being recognised. On a recent visit to Coventry I saw the 2017 blue plaque dedicated to him, the first black man to manage a theatre in England, which he did in 1828. It’s unlikely that Paul Robeson knew about this as the information has only recently been uncovered by Tony Howard himself but he would have approved. Robeson’s acknowledgement of his predecessor was a typically modest gesture in a career that was about celebrating black history as much as his own achievement.

If you’d like to hear Robeson’s glorious voice here’s a link to a clip of him reciting “It is the cause”.