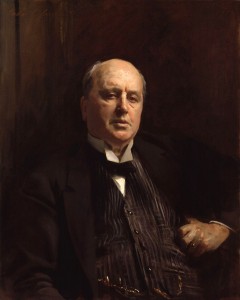

28 February 2016 is the centenary of the death of the author Henry James. James was born in 1843 in New York but spent most of his adult life in Europe, particularly England. His early novels explore the conflicting cultures of Europe and America and often focus on the lives of young, wealthy women. In novels like The Portrait of a Lady James explores the minds of his characters, often at great length, allowing their thoughts to run on uninterrupted for many pages. His interest in psychology can also be seen in his popular novella The Turn of the Screw.

As with Shakespeare, James’s private life is now a source of great interest, in particular his sexuality. Colm Toibin explains the controversies in an article in the Guardian on 20 February. He had written one volume of autobiography and after his death it was decided to publish a volume of his letters, his family demanding severe cuts. Even so James’s sister in law wrote “People are putting a vile interpretation on his silly letters to young men. Poor dear Uncle Henry.” Toibin notes it’s now possible to read James “as a gay writer whose efforts to remain in the closet gave him his style and may, in fact, have been his real subject”, making him in fact our contemporary.

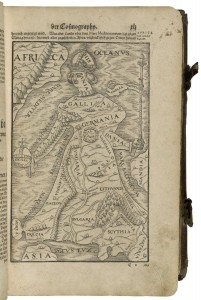

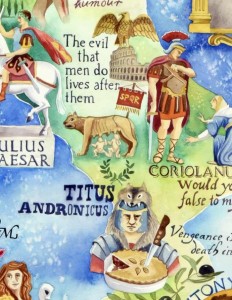

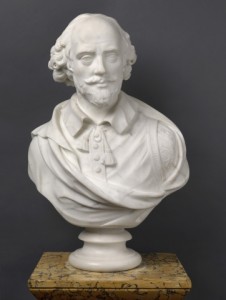

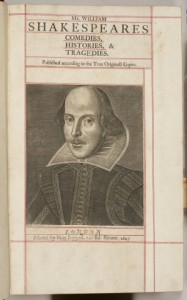

Henry James can certainly seem distant from us today, and distant too from Shakespeare. James was known to be sceptical about the authorship of Shakespeare’s plays, and his ambiguous lines in a letter to his friend Violet Hunt are often quoted: I am “a sort of“ haunted by the conviction that the divine William is the biggest and most successful fraud ever practiced on a patient world. The more I turn him round and round the more he so affects me. But that is all – I am not pretending to treat the question or to carry it any further. It bristles with difficulties, and I can only express my general sense by saying that I find it almost as impossible to conceive that Bacon wrote the plays as to conceive that the man from Stratford, as we know the man from Stratford, did.

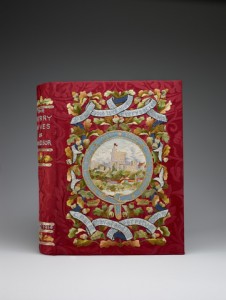

James met Sir George Otto Trevelyan in 1877 and became good friends with him and his family, visiting them often over the next thirty years or so. Trevelyan was a scholar and statesman, living at Welcombe House, just outside Stratford-upon-Avon. His son George Macauley Trevelyan became an eminent historian. Their huge country mansion is now the Welcombe Hotel. The story of James’s connection with Stratford is told in James Shapiro’s book Contested Will. While staying at Welcombe, James made several visits to the Birthplace. He didn’t record his impressions, but Shapiro suggests he may have shared his brother’s view that the “absolute extermination and obliteration of every record of Shakespeare save a few sordid material details, and the general suggestion of narrowness and niggardliness with the way in which the spiritual quantity of Shakespeare has mingled into the soul of the world, was most uncanny”.

While staying at Welcombe James was told the story of how Northumberland-born poet Joseph Skipsey and his wife, appointed to be custodians of Shakespeare’s Birthplace in 1889, had become disillusioned and left after just a couple of years. James recorded this story in 1901 in his notebook: the Skipseys had found that their job was “full of humbug, full of lies and superstition imposed upon them by the great body of visitors, who want the positive impressive story about every object, every feature of the house, every dubious thing – the simplified, unscrupulous, gulpable tale…and they ended by contracting a fierce intellectual and moral disgust for the way they had to meet the public”.

It was this story, with the conflict between art and commerce at its heart, that became, in 1903, The Birthplace, one of a collection of short stories. In James’s story Shakespeare is not named, and the couple, the Gedges, do not leave the house, but instead embrace the myth: “Gedge’s act is so successful that receipts soar and his salary is doubled. He has managed to turn his radical doubts about the Bard into art – and is rewarded for it”.

James’s other piece of writing about Shakespeare is his essay on The Tempest. In it he pondered “how could the genius who wrote it renounce his art at the age of forty-eight and retire to rural Stratford?…What became of the checked torrent, as a latent, bewildering presence and energy, in the life across which the dam was constructed?” Shapiro comments: “the essay is as much about James’s own genius and legacy as about Shakespeare’s”, His subject was “how he himself should be read and valued by posterity”.

An afternoon devoted to that genius and legacy, entitled Henry James: Shakespeare and Horror, is to be held at the British Library on 16 April 2016. Presentations will be given by leading scholars on different aspects of his work, including Professor Sarah Churchwell on what is probably James’s best-known work The Turn of the Screw, and Professor Adrian Poole on “The romance of Certain Old Texts: James and Shakespeare”. He has written extensively on both Henry James and Shakespeare and on this occasion will be examining the threat of violence in James’s work and the way that Shakespeare’s plays Othello and Hamlet infiltrate James’s writing. He’ll also be comparing the legacies that Shakespeare and James leave in this centenary year.