I’ve recently listened to an illustrated podcast of a talk given by Professor Michael Dobson in September 2012 at the Shakespeare Institute in Stratford, entitled A boy from Stratford 1769-1916, freely available on the Backdoor Broadcasting site.

The lecture was mostly about the Warwick Pageant that took place in the grounds of Warwick Castle in July 1906. I knew next to nothing about pageants apart from having read Virginia Woolf’s posthumously published novel Between the Acts, that features a 1939 country pageant staged in the shadow of the gathering clouds and rain of war : “Down it poured like all the people in the world weeping. Tears. Tears. Tears.”.

Virginia Woolf’s pageant deliberately harks back to an earlier time, and pageant-mania had begun decades earlier at the historic town of Sherborne in Dorset in 1905 when playwright Louis N Parker wrote what he originally called a folk play before hitting on the catchier name of a Pageant. To quote F A Mackenzie’s book Wonderful Britain:

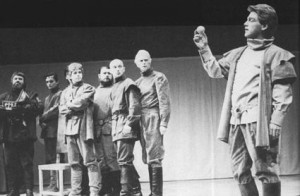

The central idea of Mr. Parker’s production was that a pageant is essentially a local affair, presenting the historic life of that locality, as far as possible amidst its own surroundings. The players are local residents who give their services voluntarily and, when they can, make their own uniforms and dresses. Pageants, as Mr. Parker viewed them, were to be held in the open air, without artificial scenery or any of the ordinary accompaniments of a stage. They differed from older displays like the Lord Mayor’s procession in that, in place of being in dumb show, they were presented more ambitiously with music, dialogue and dramatic movement.

Set in the grounds of Sherborne Castle, it set a precedent. Eleven historical scenes were staged, followed by Morris and Maypole dancing, and ended with a final procession of all the participants. It was important that this was a community event, offering “the great incentive to the right kind of patriotism; love of hearth; love of town; love of country; love of England”. Pageants told the “story of England through the idiom of local experience”. An AHRC-funded project, The Redress of the Past, is currently examining the history of pageants, and its website already includes much interesting material.

An approach for Mr Parker to create something similar for Warwick followed almost immediately. Their pageant was staged in the grounds of Warwick Castle and was on a much larger scale than that in Sherborne. 1500 people took part and the specially-built grandstand was packed with 5000 spectators for each afternoon from 2-7 July 1906.

What, though, did it have to do with Shakespeare?

Pageants became so popular that almost every historic town in the country seems to have had one: York, Scarborough, Dover, Cardiff, Bristol, Stafford, St Albans, all had their own. An inspiring pageant-master was essential, and Frank Benson, organiser of the Stratford Shakespeare Festivals, was in charge of the Romsey Pageant in 1907 and the Winchester Pageant in 1908. In 1927 he directed the spectacularly successful Scots National Pageant in Edinburgh, staged amid the ruins of Craigmillar Castle. Nearly 3000 people took part with 10,000 spectators including the King and Queen.

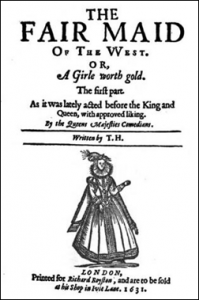

Louis N Parker’s script for Warwick included, as Episode 7, a scene lifted from Shakespeare’s play Henry VI Part 3, in which the Earl of Warwick (the Kingmaker), goes to the French court to arrange a dynastic marriage between King Edward and a French Princess, only to be told that Edward has married the English widow Elizabeth Grey.

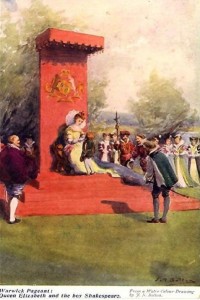

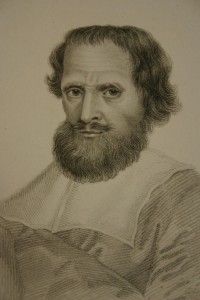

But the most striking bit of the Warwick Pageant for anyone interested in Shakespeare came in Episode 10, when Queen Elizabeth 1 was entertained at Kenilworth by her favourite the Earl of Leicester. It has long been supposed that Shakespeare, with his father, might have visited Kenilworth to see the festivities, but the Pageant took this idea much further. The Stratford-on-Avon Herald on 6 July 1906 reported that “a charming little incident” was performed during this episode. “The Bailiff of Stratford-on-Avon (Mr G W Everard) is presented [to Queen Elizabeth] and by his side trots a dear little boy of eight summers, clad in green velvet doublet, brown shoes and stockings, white collar and black velvet hat. It is no matter of wonder he strikes the fancy of the queen… he tells her his name is William – William Shakespeare, and fearlessly asks her for a kiss”.

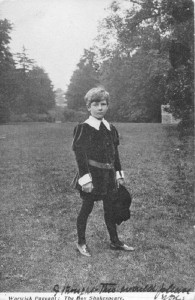

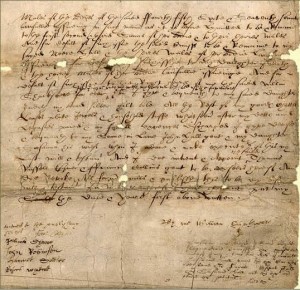

It was a feature of pageants that wherever possible the characters should be played by descendants of those portrayed. And while some people’s names were widely reported, such as Mr Everard, others were anonymous. In particular, William Shakespeare was played by “A boy from Stratford”. Mr Everard turned out to be, if not a descendant of John Shakespeare, a Stratford man, the Managing Director of the Mill, and lived in Avonfield, on Mill Lane (now replaced with a modern house of the same name). Mr Everard was also on the Town Council so was a pretty good match for John Shakespeare.

But there was more, as the official guide explained. The pageant ended with the National Anthem “Then, to the strains of solemn music, the march past begins [this was a procession of all the participants in the pageant], and the last figure left on the Arena is that of the little boy William Shakespeare. As he goes out, he kisses his hand to the audience in token that the Pageant is ended”. It must have been a satisfying end to the occasion, even if it had little to do with Warwick itself.

Michael Dobson’s essay ends with the speculation that the anonymous “boy from Stratford” is probably one of the young men whose names are inscribed on the War Memorial in Stratford. He would have been just the age to be sent off to the trenches in World War 1. The identity of the boy was a mystery that I felt needed exploring, and in a week or two I’ll be writing another post to explain what I’ve found out about the little boy who gazes so wistfully out of the photograph.