As You Like It was in the very first season of plays performed at the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre in April-May 1879. With its references to the Forest of Arden the gently romantic comedy was bound to please. The other Shakespeares in Barry Sullivan’s season were the sure-fire comedy Much Ado About Nothing and Hamlet. But it was As You Like It, given just two performances, that created the biggest impression, and a couple of reports of the closing performance on 3 May still exist.

Mary Elizabeth Lucy, from Charlecote, was there: “we all went to the comedy of As You Like It, one of my favourite plays of Shakespeare. My dear grandchildren were wild with delight when in Act Two Scene One, the Forest of Arden, a Charlecote deer (which their papa, as requested, had shot for the occasion) appeared on stage, and Masters, the Charlecote keeper dressed up as a forester, led on two of the deer hounds. The effect was charming and the house rang with shouts of applause and encore. We all came home saying we had never enjoyed a play so much before’. This extract from Mary Elizabeth Lucy’s Memoirs was quoted in a post on the Charlecote Park blog.

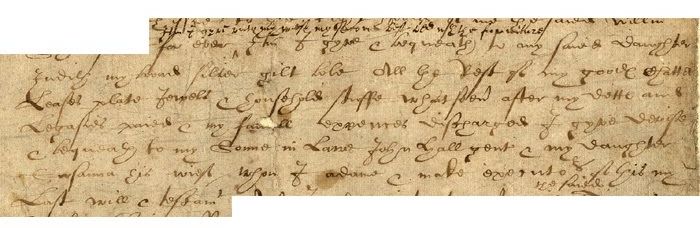

The other account was written by Sarah Flower, the wife of Charles Edward Flower, the chairman of the theatre. “Some of the actors went to Charlecote and asked Mr Lucy if he would let them have a deer from his park – he readily assented, and it was brought on this evening – his keepers and some dogs also appearing on the stage.

It was put into the mouth of one of the keepers that he said boastingly “Lots of people come from all round the country and even from London to see me and my dogs”. The deer was afterwards stuffed and kept as a property slung up in the picture gallery to be used always in this play. ”

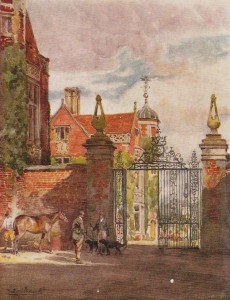

Reviewers commented on this scene, and special photographs were taken. As well as the deer, the dogs, and the Charlecote keeper, the sumptuously leafy designs by theatrical artist John O’Connor were seen for the first time. The Stratford-upon-Avon Herald commented “the scene was most picturesque”. O’Connor’s watercolour sketches for the forest sets and many other scenes for the Memorial Theatre still exist in a large volume now kept in the Theatre’s archives. The Saturday Musical Review approved: “In answer to the query What shall he have that killed the deer? the glee of that name was sung in a manner which would do credit to any choir in the kingdom”. Again as mentioned by the Stratford-upon-Avon Herald, “all the performers were Stratfordians”.

It’s easy to see how this scene came to be a cherished part of every production of As You Like It. But the Benson Company, taking over in 1886, didn’t produce the play at all until 1894, a gap of 9 years and the longest time this play has ever been absent from the Stratford theatres. It became a favourite, given one or two performances almost every year. The three Benson prompt books in the RSC’s archives show how the play was cut and scenes moved around. Each was marked up for different performance conditions (the Bensons toured widely), but all indicate a procession happening, rather oddly, in the scene where Celia tells Rosalind that Orlando is in the forest. The most elaborate prompt book mentions not just the deer but the dogs as well.

Sarah Flower mentions that the deer was stuffed and hung up in the Theatre’s Picture Gallery, and photographs confirm this. But whoever invented the ritual, it wasn’t Benson, as the deer had been shot fifteen years before his first production. The deer (or maybe a replacement by then) made its last appearance in 1915.

In the first Festival after the end of the First World War it became clear that the deer had made its last appearance. As You Like It was one of the plays to be staged by Nigel Playfair’s company from Hammersmith. As J C Trewin wrote in his book Benson and the Bensonians, “in the quick spring of 1919, it was the hour for change”. The actors were under-rehearsed, and new to Shakespeare. And Playfair’s style was very different. He engaged the designer Claud Lovat Fraser, who, inspired by medieval illustrations, designed brightly-coloured, “daringly outrageous” costumes, and, worse, “not a single leaf in the show”. Trewin again: “It was new broom Shakespeare in a theatre nurtured on tradition”.

The story is now famous that the omission of the stuffed deer caused the outrage of locals. Robert Smallwood, in his book on the play in the Shakespeare at Stratford series calls it “one of the most notorious episodes in the performance history of As You Like It at Stratford (or anywhere else for that matter)”. Although the Morning Post (not a local paper) review suggested that the audience was “tickled rather than irritated” by the innovations, “it was unmistakeably in favour of what it was used to”. The Stratford-upon-Avon Herald pleaded “restore our scenery and our dresses”. Maybe too the audience weren’t used to watching the full text of the play, briskly performed.

Specific regrets at the passing of the Charlecote deer, though, are difficult to find. The Morning Post is one of the few papers to mention it: “one never quite grasped the point of featuring as fresh killed venison the stuffed deer that had for many years been one of the mustiest exhibits in the Memorial museum”. Reports in the local press, several pages long, concentrated on Frank Benson’s lecture on wartime experiences, “The Song of the Shrapnel” and the formal tributes made to him and Lady Benson, acknowledging their tireless work for Shakespeare and Stratford. The deer may have been a nostalgic symbol of the past, but in the outpouring of emotion that accompanied the end of the Benson era I doubt that many tears were really shed for it.