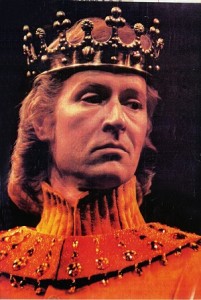

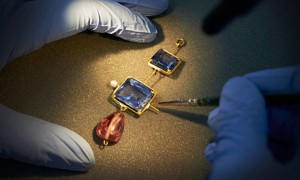

On Friday morning BBC Radio 4’s Today programme included a feature about theatre history relating to David Tennant’s current role as Richard II. On the press night Tennant received a package from Ian Richardson’s widow Maroussia Frank containing the ring that Richardson had worn when he played the role in the same theatre in 1973 and 1974. Tennant now wears the ring for every performance. The piece is at 2hrs 49 into the three-hour programme, and this is a link to the story.

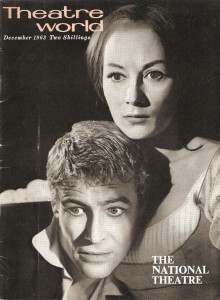

David Tennant admitted the history of Shakespeare in Stratford makes the experience of performing there rather intimidating, and said he wanted to wear the ring “to have a bit of Ian Richardson on stage with me, giving me a hand”. The RSC has a formidable record of performing Richard II, but of all their productions, none has a reputation to match that in which Ian Richardson appeared. In 1973 John Barton, the most intellectual of the RSC’s directors, emphasised the parallels between Richard and Bolingbroke by having two actors, Richardson and Richard Pasco, alternate the roles. Although Pasco is now much less familiar to the public he had already played the role for John Barton, and was well-known for his mellifluous verse-speaking. Using Richard II’s love of role-play, the production revelled in theatricality.

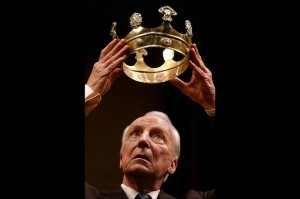

The moment where the two men each held the crown was central:

Give me the crown. Here, cousin, seize the crown;

Here cousin:

On this side my hand, and on that side yours.

Now is this golden crown like a deep well

That owes two buckets, filling one another,

The emptier ever dancing in the air,

The other down, unseen and full of water:

That bucket down and full of tears am I,

Drinking my griefs, whilst you mount up on high.

At the start of each performance Pasco and Richardson appeared to decide which of them was to play which role (though this was decided in advance). The two men had similar hair and beards. In the broken mirror, reduced to a crown-shaped frame, Richard literally came face to face with himself. And when Richard was in prison, the groom who visited him was revealed to be Bolingbroke.

Between 1960 and 1975 no actor was more closely associated with the RSC than Ian Richardson. Among his Shakespeare roles were Berowne in Love’s Labour’s Lost, Proteus in The Two Gentlemen of Verona, Prospero in The Tempest, Oberon in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Richard III, Angelo in Measure for Measure, Pericles, Coriolanus, Iachimo in Cymbeline and Ford in The Merry Wives of Windsor. Michael Billington’s obituary in 2007 indicated how important Richard II was:

If any single production staked his claim to greatness, however, it was John Barton’s 1973 Richard II in which Richardson and Richard Pasco alternated the roles of the king and Bolingbroke. Christopher Ricks, on the BBC radio programme, The Critics, vividly described Richardson’s Richard as “like Charles I in the first half and Jesus Christ in the second”. For my part, I recall his mixture of infinite sweetness, bruising irony and thunderous scorn. And Barton’s radical notion of Richard and the usurper as mirror-images of each other paid off brilliantly with the transition of Richardson’s Bolingbroke from apparently innocent victim to guilt-haunted wreck. Richardson and Pasco between them redefined the play.

After 1975 Richardson moved on, taking the role of Henry Higgins in a stage version of My Fair Lady (an ideal role for him, given his cut-glass diction), later becoming a household name through television series such as Tinker, Tailor, Soldier Spy and the House of Cards trilogy.

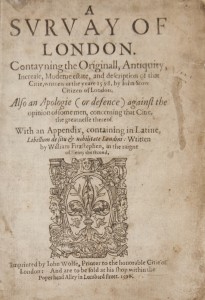

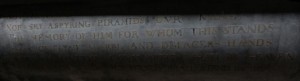

His last Stratford performances were in 2002 when he went back to the RST for a run of John Barton’s recital programme The Hollow Crown with other distinguished Shakespeare actors Donald Sinden, Derek Jacobi and Janet Suzman. The programme examines the history of the kings and queens of England, and Richardson memorably recited the speech from Richard II that gives the programme its name, with which he was so closely associated.

He died in his sleep in 2007, and when his widow and younger son Miles, an actor with the RSC, visited the theatre during its transformation, it occurred to them that it would be appropriate for Ian’s ashes to be placed there. This wish was granted. So it isn’t just the ring that David Tennant can call on for a bit of moral support when on stage.

Just in case you haven’t heard, Richard II is going to be streamed Live from Stratford-upon Avon on 13 November to cinemas around the country. Lots of information about the production is available on the RSC’s website, including production diaries offering a fascinating insight into the show and some video clips from the dress rehearsal, very much worth a look even if you’re not able to get to the play itself.