I was delighted to hear, a few weeks ago, that actor Simon Russell Beale has been awarded a knighthood. I’ve always enjoyed seeing him on stage and television, in particular watching him taking on many of Shakespeare’s most challenging roles.

He began his career with the RSC in 1986, the year in which the Swan Theatre opened. This venue turned out to be perfectly suited to his unshowy style of acting, its intimate size and thrust stage allowing more direct communication with the audience than the much larger RST. He was in two plays in that first season, Every Man in His Humour and The Fair Maid of the West. He also played the Young Shepherd in The Winter’s Tale in the RST, and the slimy Oliver in The Art of Success in The Other Place. It was a strange mix of comic roles, supporting roles, or one-dimensional villain.

The only time I’ve ever met him was before I’d seen him on stage: while rehearsing Every Man in His Humour the actors must have been given a bit of research to do, because he and another actor turned up at the Shakespeare Centre Library. Introducing himself, I remember Simon laughing as he explained, standing next to the extremely handsome Nathaniel Parker, that he was playing the romantic lead in the play.

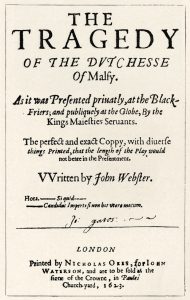

It was as if the RSC hadn’t yet worked out what to do with this obviously talented actor: in his next season, 1988, he played a series of fops, outrageously camp rather than subtle. But then there came a number of terrific performances: Konstantin in Chekhov’s The Cherry Orchard, Thersites in Troilus and Cressida, the King in Marlowe’s Edward II, Ariel in The Tempest, the title role in Richard III, Oswald in Ibsen’s Ghosts. He was the first winner of the Ian Charleson award in 1991 for four of these performances with the RSC.

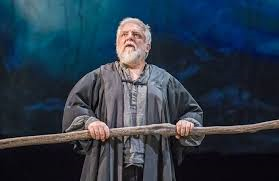

Since 1994 he’s done most of his stage work in London, particularly at the National Theatre. I’ve been lucky enough to see quite a few of his roles, mostly Shakespeare. Hamlet, Timon of Athens, King Lear, Uncle Vanya, Malvolio, Cassius in Julius Caesar. A few years ago he returned to the RSC to play Prospero in The Tempest. He’s often been in productions, like Timon of Athens, that have taken liberties with Shakespeare’s text, and this one also introduced extravagant computer-generated visuals. He’s on record as saying that we shouldn’t be too reverential towards Shakespeare, as he’s quite robust enough to withstand whatever we do to him.

Simon Russell Beale almost always has an introspective, vulnerable quality. All actors do more than speak the words, but he finds the humanity of the part and finds a way of conveying it without speaking. As I’ve already mentioned in a blogpost, in The Tempest he managed by a single action to show how much his Ariel had always resented Prospero for making a slave of him, his emotionless façade there to protect himself. Lear’s probably the most ambiguous of characters – a difficult man to like, but whose suffering and fall demand our sympathy (or should). He’s the only Konstantin I’ve ever seen who didn’t come across as just a spoiled brat. I’ve seen and heard lots of actors delivering the “What a piece of work is a man” speech in Hamlet, but when he delivered it, it felt to me like a cry from the heart.

I’m sorry to have missed most of his recent work onstage, but he’s been on TV presenting Sacred Music, a series about choral music (he was a chorister at St Paul’s Cathedral).

Over the August Bank Holiday weekend in 2019 he could be heard in the reading of Marcel Proust’s In Search of Lost Time, adapted by Timberlake Wertenbaker into ten hours of radio. Along with Simon Russell Beale they recruited an amazing cast including Derek Jacobi, Sylvestra le Touzel, Paterson Joseph and Frances Barber. It’s a book that is best known for being exceptionally long, and it’s certainly an achievement to get through the whole thing. I had to admit defeat when I tried reading the books several decades ago, so I hoped that listening would make up for it. But then the Bank Holiday weekend turned out to be gorgeously warm and sunny, so I, and I suspect many others, spent it outdoors. The good news is, though, that we can enjoy it as the evenings draw in.

Here are a couple of links, too, to him being interviewed by Melvyn Bragg about King Lear and him delivering a few short bits of Shakespeare to camera.