Hung be the heavens with black, yield day to night!

The opening line of Henry VI Part One seems appropriate as a memorial for the great theatre director Terry Hands, who died on 4 February 2020. The success of the Royal Shakespeare Company in the 1970s and 1980s was in large part due to him and since his death a number of obituaries here and here have been published outlining his career.

A serious-looking, tall, spare figure usually dressed in black, Hands was intellectual and articulate. His productions were visually striking, but never over-decorated. Rather than using elaborate scenery he painted the stage with light, often taking on the role of lighting designer, and relied heavily on the effect caused by the costumes and props created by the great designer Farrah, particularly in the history plays. The climax of his Henry V, when Alan Howard, newly-crowned, marched slowly and stiffly downstage wearing a dazzling gold suit of armour charted Howard’s progress from madcap prince to untouchable King perfectly.

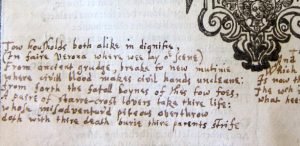

The RSC in the 1960s was dominated by The Wars of the Roses, a conflation of the three parts of Henry VI into two, completed by Richard III. It was a risk to challenge its success, and the full Henry VI trilogy was widely regarded as unstageable. Hands was successful and the trilogy became one of the productions that defined the RSC as a risk-taking, ambitious company. Casting too was risky combining established actors Alan Howard and Helen Mirren as King Henry VI and Queen Margaret, with Anton Lesser, pretty well straight out of drama school, as Richard III.

Hands is usually thought of as a serious director of political plays and tragedies, but he successfully directed his fair share of comedies. Much Ado About Nothing, with Derek Jacobi and Sinead Cusack, was a hit, and, combined with Cyrano de Bergerac, transferred to the USA. Poppy, by Peter Nichols, sounded unlikely: a musical comedy in the style of a pantomime on the subject of the nineteenth-century Chinese opium wars, but with Hands’ sure-footed direction it transferred to the West End after its initial Barbican Theatre run.

Another surprise treat that showed Hands’ lighter side was the RSC’s own pantomime written by company-member Bille Brown and staged at the end of the 1980 season, The Swan Down Gloves. Leading members of the company clearly enjoyed letting their hair down. The most delicious in-joke of the evening came when George, the Silent Dragon, having moped around the stage during the evening, finally found his voice and was revealed, of course, to be the company’s leading tragedian Alan Howard. It’s for his working relationship with the late Alan Howard that Hands may best be remembered, and in 2011 the two came together to reminisce on the stage of the RST.

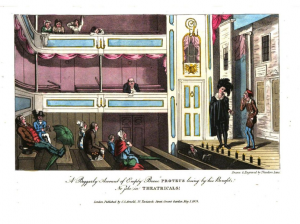

While he had many successes on the large stage, he played an important role in developing the RSC’s small-scale work. During the 1960s he was brought in specifically to run outreach work in schools, founding a touring branch of the RSC called Theatregoround. Rather than featuring a “second 11”, actors from the main Stratford company went off in groups to deliver a variety of plays and recitals around the country. This work led directly to the founding of The Other Place in Stratford where the strategy of using the main acting company to put on productions on a shoe-string was applied again.

After the opening of the Swan Theatre in Stratford in the mid 1980s Hands directed a number of plays in this intimate auditorium with considerable subtlety and sensitivity. Romeo and Juliet and Singer in 1989, and one of my favourite productions ever, Chekhov’s The Seagull in 1990 that featured the up and coming Simon Russell Beale.

I never met Terry Hands, but I have a favourite memory of him. It dates back to 11 July 1989. I was attending the performance at the RST, and the death of Sir Laurence Olivier had just been announced. Before curtain up, Terry appeared on stage and, rather than asking for a minute’s silence or dimming the theatre lights, both traditional ways of marking the passing of a notable person, he asked the audience give Olivier one final standing ovation. It was typical of Terry Hands to think of such a beautifully-judged tribute to this great man of British theatre.