Historian Dr Robert Bearman has contributed today’s post, which revolves around a chance discovery which he made recently in the Shakespeare Centre Library and Archive.

Those wishing to know more about Shakespeare’s life may fantasise about making a major archival discovery but the fact is that very little has been added to the direct documentary record since the discovery over a hundred years ago of Shakespeare’s involvement in the Bellot/Mountjoy case. So we have to be satisfied instead with the occasional emergence of those slivers of evidence which throw a little more light on what was going on around him. This was my feeling when I recently stumbled more or less by chance on the names of three travelling companies of players who visited Stratfordin the summer of 1597, the year Shakespeare bought New Place. These visits were already on record in outline form and have been known about for some time: for Stratford’s chamberlain, in his accounts for that year, had included a payment of 19s 4d to reimburse the bailiff, Abraham Sturley for money he had laid out ‘for foure companyes of players’. But on the back of a bill (still extant in the borough archives) which formed another item in the accounts, I found that Sturley had jotted down further details of these playing companies, principally ‘the Queens plairs’, who were given 10 shillings on 16 and 17 July. He then adds, more scruffily and in a different ink, the names of two other troupes, ‘Therle of Darbies’ and ‘mi Ld Ogles’, though not specifying the payments received. Given that the Queen’s Men were rewarded with two payments totalling 10 shillings, perhaps the total of 19s 4d was the outlay for four performances, rather than to ‘four companyes’.

I cannot, in fact, claim this to be an entirely new discovery. Back in 1923, E.K. Chambers, in his English Stage, refers to these visits by the Queen’s Players and the Derby’s Men (though not Lord Ogle’s) but misdated them and failed to name his source. As a result they have since gone unnoticed and it was therefore still a matter of some satisfaction to be able to authenticate and amplify what had become virtual hearsay and to pass the relevant data on to the REED project.

Nobody knows more about the records of Stratford-upon-Avon in Shakespeare’s time than Dr Bearman, and I’m grateful to him for sharing his find with this blog.

Information about the activities of acting companies is being brought together by the Records of Early English Drama (REED) project mentioned by Dr Bearman, headed by the University of Toronto. Since 1975 contributors have undertaken the massive job of searching for these elusive records. 27 volumes have now been published, many of which are searchable online through the Patrons and Performances website.

Information about the activities of acting companies is being brought together by the Records of Early English Drama (REED) project mentioned by Dr Bearman, headed by the University of Toronto. Since 1975 contributors have undertaken the massive job of searching for these elusive records. 27 volumes have now been published, many of which are searchable online through the Patrons and Performances website.

Although the records are only partial, it’s exciting to be able to get a sense of where companies toured to: theatrical action most definitely didn’t only happen in London.

In Hamlet, much of the plot turns on “the tragedians of the city” who visit Elsinore “to offer you service”. Hamlet describes the touring company:

He that plays the king shall be welcome :the adventurous knight shall use his foil and target; the lover shall not sigh gratis; the humorous man shall end his part in peace; the clown shall makes those laugh whose lungs are tickly o’th’sere; and the lady shall say her mind freely.

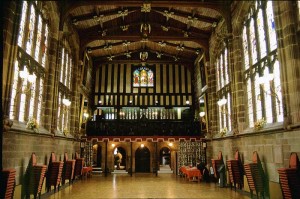

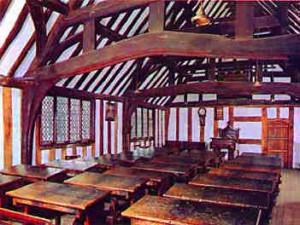

On the REED database searches can be made by company or venue, and venues can be shown on a map. The records for Coventry, the nearest important city to Stratford, are already online. In fact it appears that all three of the companies that appeared in Stratford in 1597 also appeared in Coventry, so perhaps they took in Stratford around the same time. Coventry’s magnificent Guild Hall still stands, though remodelled and re-roofed, and we can be pretty certain that Shakespeare performed there during his company’s visit in 1603. This wonderful resource will become even more useful as records are added.

The records Dr Bearman has rediscovered are tantalising: how much else is there still waiting to be found scribbled on the back of another document?