I’ve only been away for a few days, but on return have found many Shakespeare-related stories to catch up on. There have been two major press nights, Othello at the National Theatre, As You Like It at the RSC. These two plays seem to have little in common except for the theme of love. As You Like It is probably the sunniest of Shakespeare’s plays, where Orlando and Rosalind are “many fathom deep in love” and Celia and Oliver “are in the very wrath of love, … clubs cannot part them”. But every play has a darker side: Orlando’s own brother plots against him and threatens him with death. His reason is the green-eyed monster of jealousy: Orlando is “gentle, never schooled and yet learned, full of noble device, of all sorts enchantingly beloved; and indeed so much in the heart of the world … that I am altogether misprized”.

Duke Frederick has exiled his brother, and is so jealous on his daughter’s behalf that he plans to get rid of Rosalind too:

her smoothness,

Her very silence and her patience,

Speak to the people and they pity her.

Thou art a fool. She robs thee of thy name,

And thou wilt show more bright and seem more virtuous

When she is gone.

Unlike Cyprus, Arden is not the place for serious jealousy, but Orlando’s statement “But O, how bitter a thing it is to look into happiness through another man’s eyes” contains a germ of Iago’s jealous observation of Othello and Desdemona’s happiness and his determination to wreck it. Their love makes all the other relationships in the play look stale. Both productions have been favourably received and I look forward to seeing them.

Also in the past week the Culture Secretary, Maria Miller, suggested that the arts, including theatre, had to make the case for subsidy by focussing on economic, not artistic value. I missed the detail of her speech, but have read some of the reactions to it. In particular, Sir Nicholas Hytner and Nick Starr, Director and Executive Director of the National Theatre, have written a terrific piece outlining the issues. Miller recognises the value of the cultural sector to Britain: if nothing else, millions of tourists are drawn to this country by our arts and culture. But as usual with politicians, she doesn’t seem to recognise the need for risk and experiment. They write:

“War Horse started as an experiment in the National Theatre Studio – literally, actors with cardboard boxes on their heads…

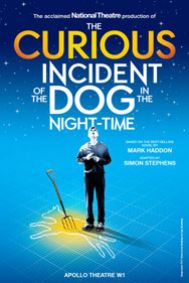

The lesson is not to ask the question, how do we create the next War Horse? It is rather to continue funding the NT Studio, where much of the most commercially successful stuff starts life. This is why the West End has largely outsourced its need for the new to the subsidised sector. They don’t regard us as the competition, but as essential to their business model. They can’t see how you would otherwise develop a Matilda or a Curious Incident of the Dog In the Night Time. ”

Hytner and Starr wrote their piece before Sunday’s Olivier awards in which The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time, a play about autism, swept the board. Marianne Elliot, the play’s director, made the same point in a BBC interview: “It was an experimental journey, and … we could not have done it anywhere else other than a properly subsidised theatre… You have to be allowed to take risks and that means being allowed to fail and that means being allowed to try new things.”

Hytner and Starr wrote their piece before Sunday’s Olivier awards in which The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time, a play about autism, swept the board. Marianne Elliot, the play’s director, made the same point in a BBC interview: “It was an experimental journey, and … we could not have done it anywhere else other than a properly subsidised theatre… You have to be allowed to take risks and that means being allowed to fail and that means being allowed to try new things.”

The piece challenges to government to adopt an arts policy based on an “overall vision for growth”, and “systematic investment” rather than the piecemeal reduction in the amount of money handed out to fewer and fewer organisations. One of the problems for theatre is that it just looks like fun. The writer Simon Stephens, responsible for the theatrical version of Curious Incident, commented that theatre is ” at it’s best when it’s collaborative, made …with a spirit of fun.”

Shakespeare’s plays are usually recognised as being much more than just entertainment, and holds his place in the education system. They’ve also been used as therapy in mental institutions, to bring deprived communities together and, most recently, Henry V has been performed by traumatised members of the armed forces as a way of helping them recover. There are many other examples of theatre being used as therapy, and as an art form it requires teamwork, collaboration, imagination and a whole host of different skills.

Only a couple of weeks ago the RSC opened Matilda and Julius Caesar in New York. It’s not likely that either Othello or As You Like It will join them, but the blockbuster shows owe a great deal to the training and skills of actors, crew and craftspeople of the major subsidised theatres. Les Miserables is the world’s longest-running musical, seen by 65 million people in 42 countries. Who now remembers that this was originally performed by the RSC at the Barbican in 1985, during another period when the arts were under fire?