The Royal Shakespeare Company is currently offering audiences the chance to see both The Taming of the Shrew and Measure for Measure back to back. These plays are unlikely bedfellows, but they have in fact a lot in common.

Both plays put a young woman centre stage, Kate and Isabella, neither of whom is going to fit in with the usual pattern of courtship, marriage and motherhood. There is no older woman to support either girl, so they are outnumbered and dominated by men. The men who surround them have trouble knowing how to deal with these two unusual women.

Measure for Measure shows us the extremes of female behaviour from the nuns Isabella intends to join, to the prostitutes working for the brothel-keeper Mistress Overdone. Juliet and Mariana are the two women who both expected to follow the path of marriage, but are prevented from doing so, and both are punished, though guiltless of anything you could seriously call a crime.

In The Taming of the Shrew the women are a puzzle to the men who think they control them. Katherina refuses to play the game that would make her a suitable wife, while her younger sister Bianca relishes it, fully aware she’s playing a role until she has the ring on her finger. There’s no indication that Kate does not want to marry, in fact she makes it clear that she is jealous of Bianca’s betrothal.

She is your treasure, she must have a husband;

I must dance bare-foot on her wedding day,

And for your love to her, lead apes in hell.

Does the absence of a mother figure itself create the possibility for drama?

The plays share concerns about restraint, imprisonment and justice. It’s right there in the title of Measure for Measure, and during the play Shakespeare shows us the formal workings of justice: a court of law, the prison where inmates are executed. Programme covers often feature the scales of justice. Juliet is incarcerated, then sent away to have her baby, Mariana lives in an inaccessible moated grange, and Isabella is about to enter the closed world of the convent.

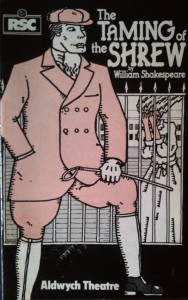

The Taming of the Shrew is often seen as a battleground in which Petruchio seems to be in control. The programme cover for the 1978 RSC production, directed by Michael Bogdanov, shows the standing figure of a dominant man holding a whip, in front of a metal fence behind which is the weeping figure of a woman. This production was put on at the height of the Women’s Liberation movement, the implication being that Kate is imprisoned and abused by her husband. Or does she impose the imprisonment on herself? You might say that Petruchio himself is a victim of his own behaviour, and in one way or another, all the characters are subject to the restraint of their conventional learned behaviours.

The third shared theme is disguise. Shakespeare often makes his characters put on a disguise, and it’s a satisfying dramatic device. In Measure for Measure, the duke disguises himself as a friar, the body of Ragozine stands in for Claudio’s, Mariana pretends to be Isabella to carry out the bed trick. Angelo’s supposed virtue is itself a kind of disguise, his real nature taking him completely by surprise. When Isabella threatens to reveal him he knows his reputation will protect him:

My unsoil’d name, the austereness of my life,

My vouch against you, and my place i’the stage,

Will so your accusation overweigh,

That you shall stifle in your own report…

Say what you can, my false o’erweighs your true.

The Taming of the Shrew has disguise at its heart from the word go. In the induction the beggar Christopher Sly is dressed up as a Lord and made to believe he is one. Tranio and Lucientio, servant and master, exchange clothes and identities. Bianca pretends to be obedient to attract suitors, and a substitute Vincentio is needed for her clandestine marriage. One of the sources of the play is another play called Supposes, in which a suppose is “nothing else but a mistaking or imagination of one thing for another”. Both Kate and Petruchio are supposed to be other than they really are. Kate is misunderstood by her father, so she adopts the disguise of a shrew. Petruchio needs to establish himself as the head of his family, so he adopts the disguise of a bully to cover his insecurity. The good thing about a disguise is that it gives you something to hide behind as well as giving you the freedom to see through other people’s disguises.

The Taming of the Shrew has disguise at its heart from the word go. In the induction the beggar Christopher Sly is dressed up as a Lord and made to believe he is one. Tranio and Lucientio, servant and master, exchange clothes and identities. Bianca pretends to be obedient to attract suitors, and a substitute Vincentio is needed for her clandestine marriage. One of the sources of the play is another play called Supposes, in which a suppose is “nothing else but a mistaking or imagination of one thing for another”. Both Kate and Petruchio are supposed to be other than they really are. Kate is misunderstood by her father, so she adopts the disguise of a shrew. Petruchio needs to establish himself as the head of his family, so he adopts the disguise of a bully to cover his insecurity. The good thing about a disguise is that it gives you something to hide behind as well as giving you the freedom to see through other people’s disguises.

Carol Rutter’s book Clamorous Voices contains discussions between five Shakespearean actresses who have played a range of parts including Kate and Isabella, and I recommend it for its stimulating insights on these two plays.