![]() Every year on 8 March International Women’s Day celebrates the achievements of women. All round the world women still suffer serious inequality, and education is one area to which even in the Western world women were denied equal access until relatively recently.

Every year on 8 March International Women’s Day celebrates the achievements of women. All round the world women still suffer serious inequality, and education is one area to which even in the Western world women were denied equal access until relatively recently.

This post is about a woman who, in the mid nineteenth century, entered the almost-exclusively masculine world of Shakespeare study. And who attempted, by her writings, to guide young women towards an appreciation of Shakespeare and other literary works.

This woman was Mary Cowden Clarke, rarely remembered now but according to Gail Marshall in her book Shakespeare and Victorian Women “the pre-eminent female scholar of the century”. Her life was enormously productive, and centred around the work of Shakespeare.

This woman was Mary Cowden Clarke, rarely remembered now but according to Gail Marshall in her book Shakespeare and Victorian Women “the pre-eminent female scholar of the century”. Her life was enormously productive, and centred around the work of Shakespeare.

She was born into the Novello family of music publishers, and through her father made the acquaintance of many distinguished people of arts and letters, including Leigh Hunt, Keats and Charles and Mary Lamb, the adapters of Shakespeare’s stories. Charles Cowden Clarke was a business partner of Novello and although he was 22 years older than her it’s clear that theirs was a love match. She was 17 when they became engaged and married eighteen months later.

The year after their marriage, Mary set about the task of creating a Concordance to Shakespeare’s works, a Verbal Index to all the Passages in the Dramatic Works of the Poet. This massive task took twelve years, and was eventually published in eighteen monthly parts, being completed in 1845. It was far superior to the existing version, and was not superseded for another 50 years.

Her next Shakespearean project was to write a series of fifteen essays which were published under the title The Girlhood of Shakespeare’s heroines. With titles including Juliet: the white dove of Verona and Ophelia: the rose of Elsinore it’s easy to see why Cowden Clarke’s work is now unrecognised, but these prequels, written in the style of much of the fiction of their time, were aimed at helping young women in particular to find a way into Shakespeare’s plays and other more worthwhile literature.

Her next Shakespearean project was to write a series of fifteen essays which were published under the title The Girlhood of Shakespeare’s heroines. With titles including Juliet: the white dove of Verona and Ophelia: the rose of Elsinore it’s easy to see why Cowden Clarke’s work is now unrecognised, but these prequels, written in the style of much of the fiction of their time, were aimed at helping young women in particular to find a way into Shakespeare’s plays and other more worthwhile literature.

Mary then moved on: she was the first woman to edit all of Shakespeare’s plays (Henrietta Bowdler, using her husband’s name, had censored 20 of them of scurrilous material in The Family Shakespeare). In 1860 Mary’s edition appeared “with a scrupulous revision of the text”. She and her husband then worked jointly on an annotated edition which was issued in weekly parts from 1863-68.

They continued to collaborate on The Shakespeare Key, unlocking the Treasures of his Style, elucidating the Peculiarities of his Construction, and displaying the Beauties of his Expression; forming a Companion to The Complete Concordance to Shakespeare, a project which took them up to 1872, though only published seven years later after the death of her husband.

By 1879, when Mary was 70 years old, she had completed a concordance, two editions, a series of essays, and a major reference work on Shakespeare. This extraordinary body of work does not include the many stories and articles which she had written and published on other subjects during her career.

By 1879, when Mary was 70 years old, she had completed a concordance, two editions, a series of essays, and a major reference work on Shakespeare. This extraordinary body of work does not include the many stories and articles which she had written and published on other subjects during her career.

In case you’re thinking that she must have been an over-serious, dull Victorian, her autobiography, published in 1896 when she was 87, is written with delightful joie de vivre and good humour. She was happy to be one of Charles Dickens band of amateur actors who in 1848 took The Merry Wives of Windsor and other plays on tour, playing the comic role of the servant, Mistress Quickly. Apparently her performance was one of the highlights of the evening.

As a final note, I discovered while researching in the Shakespeare Centre Library and Archive a book which had once belonged to Mary Cowden Clarke. It’s a copy of Edward P Vining’s book The mystery of Hamlet: an attempt to solve an old problem, 1881. Vining was a well-known actor who had played Mercutio in the 1864 Tercentenary celebrations in Stratford-upon-Avon. His book suggests that Hamlet is not only a womanish man, but, “in very deed a woman, desperately striving to fill a place she was by nature unfitted”. The flyleaf of the SCLA copy contains Mary’s decisive handwritten comment that the premise of the book was “preposterous”.

What a fascinating piece. Mary Cowden Clarke seems definitely to have been a Good Thing and I had not realised that it was Mrs Bowdler who had wielded the blue pencil.

Very interesting:); but in fact women still are denied equality of access to education. Those who are not wealthy may, through intense hard work , be permitted to attain a token BA and possibly an MA – but how many women from ( for example) a council estate in Liverpool or Newcastle will achieve a doctorate from Oxford, Cambridge or even Birmingham; and how much of this is attributable to external barriers rather than lack of ability, aptitude or inclination?

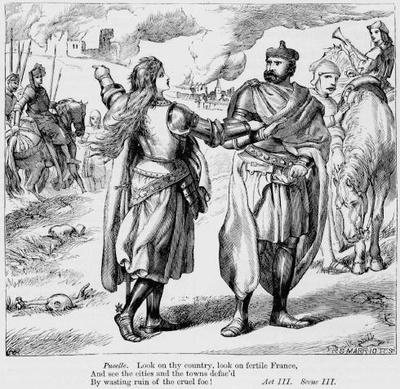

Great piece Sylvia. How nice to see a photo of Mary – she certainly doesn’t look like a dull Victorian! And I love the Henry VI illustration.

Mary Cowden Clarke deserves much more recognition I think. The Girlhood of Shakespeare’s heroines makes her easy to dismiss because they are so anachronistic. But she managed to be serious without being dull, quite an achievement for the time!