I’m no great lover of any sport involving animals, but I do admire the beauty of those superbly athletic thoroughbred horses. It was shocking to hear that two horses had died during the running of last weekend’s Grand National, one of them the extraordinary horse Synchronised which only weeks ago won the Cheltenham Gold Cup. No matter how successful they are, these horses exist only for the benefit of the people who own, train, ride and bet on them.

Horses have been bred and kept by man for millenia, for a whole variety of purposes. One of the ways we know about how horses were viewed in Shakespeare’s day is from Topsell’s History of Four-Footed Beasts. This encyclopaedia of animals from mice to elephants is 586 pages long, of which the section on horses takes up 120 pages, far more than any other creature. His opening introduction is an affectionate tribute:

When I consider the wonderful work of God in the creation of this Beast, enduing it with singular body and a noble spirit, the principal wherof is a loving and dutiful inclination to the service of Man; wherein he never faileth in Peace nor war, being every way more neer unto him for labour and travel: and therefore … we must needs account it the most noble and necessary creature of all four-footed Beasts, before whom no one for multitude and generality of good qualities is to be preferred, compared or equalled.

The section is divided up into descriptions of different kinds of horses: “of coursers, or swift light running horses”, “of careering horses for pomp or triumph”, and “of load or pack horses”. Horses could be used “for War, and Peace, pleasure and necessity”.

Topsell encourages grooms to be affectionate to their charges: “and evermore there must be nourished a mutual benevolence betwixt the Horse and Horse-keeper, so as the Beast may delight in the presence and person of his attendant”. Horses are supposed to be sensitive, loving music, and “have a singular pleasure in publick spectacles”.

Many of Shakespeare’s mentions of horses relate to the close bond between rider and horse. In Henry V the French Dauphin so loves his horse that he writes a sonnet in its praise. And in Richard II it’s a groom who visits Richard in prison to tell him how Bolingbroke, the new king, rode Richard’s own horse in his coronation procession:

O, how it erned my heart when I beheld,

In London streets that coronation day,

When Bolingbroke rode on roan Barbary!

That horse that thou so often hast bestrid,

That horse that I so carefully have dressed!

Richard’s initial reaction is to feel betrayed:

That jade hath eat bread from my royal hand,

This hand hath made him proud with clapping him.

Before realising that the horse is only doing what it has been trained to do:

Forgiveness, horse! Why do I rail on thee,

Since thou, created to be awed by man,

Wast born to bear.

Horseriding for pleasure: a detail from a 1480 French book of hours from a manuscript in the Morgan Library, New York

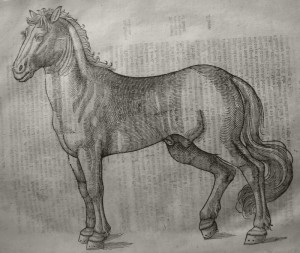

The fullest description of a well-bred horse is Adonis’s unruly steed in Venus and Adonis:

Round-hoof’d, short-jointed, fetlocks shag and long,

Broad breast, full eye, small head, and nostril wide,

High crest, short ears, straight legs and passing strong,

Thin mane, thick tail, broad buttock, tender hide:

This literal description prompted the critic Dowden to ask: “is it poetry or a paragraph from an advertisement of a horse sale?” but Shakespeare shows an appreciation of the qualities of a fine horse.

Not all the horses in Shakespeare are owned by royalty or the nobility: in Sonnet 50 he writes how “the beast that bears me… plods dully on” and ordinary horses are mentioned over and over again in the plays and poems.

After thousands of years in which horses were used for everything, it always surprises me that within a few decades we lost our connection with them. A hundred years ago everybody would have been familiar with horses, whether they were making deliveries around town, working on farms, or being ridden for pleasure. Watching horseracing is now most people’s only link with them.

There is one kind of work in which the working horse is making a comeback. The tree-felling industry is now using placid, strong breeds like the Ardennes, originally from Belgium. Horses are able to work in forested areas where powered vehicles are difficult to manoeuvre, and horses would have worked in the Forest of Arden where Shakespeare’s mother was born and brought up. This photograph of one of the working horses was taken recently a few miles from Stratford-upon-Avon.

Man’s relationship with horses may have changed over the centuries, but it shows no sign of ending.

Think, when we talk of horses, that you see them, printing their proud hooves i’th’receiving earth….

Fascinating! I always found the part from Richard II very touching – how betrayed he felt by his horse. Thanks for this one

Not so sure that I share this slightly rose-tinted view of the horse; have had a few too many riding injuries for that; ‘let the galled jade wince, my withers are unwrung’…! 🙂