In November 1786 the printer Josiah Boydell held a dinner at his London home to which he invited several leading artists including George Romney and Benjamin West. The discussion turned to the idea of creating a lavishly illustrated edition of Shakespeare’s plays.

Within a week the Boydells, Josiah and his uncle John, announced a more ambitious plan. A Shakespeare Gallery was to be opened, hung with newly-commissioned oil paintings depicting scenes and characters from Shakespeare’s plays. Large engraved prints of the paintings, published by the Boydells, would be sold by subscription, and small versions of the images would be used to decorate an edition of Shakespeare’s works.

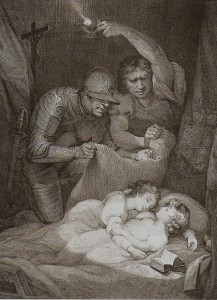

King Richard III Act 4 Scene 3. the smothering of the princes, by James Northcote, engraved by Francis Legat

The Boydells were already successful printers, engravers and publishers, and hoped that the Gallery would be both commercially and artistically successful, with the specific aim of promoting British painting. Most British painters specialised in portraiture: even images of Shakespeare on stage tended to be portraits of eminent actors in role. History painting, taking grand events as its subjects, and communicating high moral values, had for centuries been seen as the noblest form of painting. It’s hardly surprising that Shakespeare, rapidly becoming the symbol of the nation, was so attractive. As John Boydell wrote in his preface to the first catalogue of the Gallery “no subjects seem so proper to form an English School of Historical Painting, as the scenes of the immortal Shakespeare; yet it must be always remembered, that he possessed powers which no pencil can reach”.

Earlier this week art historian Paul Lewis gave a lecture to the Stratford-upon-Avon Shakespeare Club on the Boydell Shakespeare Gallery which put the Gallery in its historical context and suggested that the paintings and engravings are worthy of the revival of interest which they’re currently receiving.

Boydell’s idea was a bold one: by getting some of the most important British painters such as Reynolds, Opie, and Fuseli involved he ensured that subscribers would pay in advance for the engravings, but the investment would be huge. Although there are now many collections of paintings open to the public, Paul Lewis reminded us that this was not the case in the late eighteenth century. There was no National Gallery, and the Royal Academy had only recently been founded. So Boydell’s Gallery, opening in June 1789 with 34 paintings on view, was a novelty, but also something of a risk.

The Gallery itself was a magnificent space. The entrance was dominated by a marble sculpture by the distinguished artist Thomas Banks, showing Shakespeare seated between the Dramatic Muse and the Genius of Painting. An engraving appears as a frontispiece to the Illustrated Shakespeare volumes published in 1803. Banks was a notable sculptor whose work included both classical statuary and public monuments to the heroes of the time. It was the one part of the Gallery that was universally admired, and Boydell at one time intended the sculpture to be placed above his grave.

The project was not without detractors. James Gillray’s engraving Shakespeare Sacrificed: Or the Offering to Avarice might have been just the revenge of a man who wasn’t invited to create any of the engravings, but it was a hugely popular shot at this very public target. Alderman Boydell stands in front of a fire in which Shakespeare’s plays are being burnt, and within the smoke is a statue of Shakespeare himself. Images from some of the paintings in the Gallery can be seen above. The figure of Avarice is the gnome-like figure perching on top of a volume of Subscribers’ names, holding two moneybags. Vanity sits on his shoulders.

The Boydell Gallery is usually thought of as a commercial failure, but Paul Lewis pointed out that it was actually a success for over ten years, during which time the number of paintings on show grew to almost 170, by 33 artists. But by the early 1800s the Gallery was no longer the height of fashion, and the war in Europe effectively closed off the trade in engravings with the Continent. By 1803-4 the Gallery was failing, and in 1805 all the contents were dispersed.

The sculpture remained in place until 1869 when it was acquired by Charles Holte Bracebridge of Atherstone Hall who presented it to the town of Stratford-upon-Avon in 1871. It now sits in a quiet corner of New Place Garden.

Paul Lewis illustrated his talk with many of the engravings and a few of the paintings. He reminded us that many of the images continued to appear in different forms until the end of the nineteenth century, and illustrated his point by showing a beautiful piece of Worcester china painted with one of the images. The Gallery also spawned several imitators: Macklin’s Poets Gallery, an Irish Shakespeare Gallery, and Fuseli’s Milton Gallery.

The engravings are still to be seen in many collections and quite by chance Yale University’s Remembering Shakespeare blog featured Boydell this week. Click here to be taken to the post. In a later post on this blog I’ll be looking more closely at the images themselves.

Wouldn’t it be wonderful to have a modern Boydell Gallery for the 2014-16 anniversaries? I’ve always loved the boldness of the original project. I’m only sorry I wasn’t at the talk.