What is the best way to commemorate the life of a writer? Why do we so often treasure the houses they lived in, and what do we hope to get out of visiting them?

What is the best way to commemorate the life of a writer? Why do we so often treasure the houses they lived in, and what do we hope to get out of visiting them?

There have been a number of recent attempts to answer this question such as Nicola Watson’s book The Literary Tourist, and Julia Thomas is the latest author to examine this issue, her book Shakespeare’s Shrine concentrating on a single house, Shakespeare’s Birthplace in Stratford-upon-Avon. Her book delves into the strange, eventful history of the building highlighting the eccentricity of people involved and events surrounding it, a story in itself so odd that I’m surprised it has received so little attention.

The fate of Shakespeare’s Birthplace became a cause celebre leading up to the auction of the house in 1847. People had been trying to get closer to Shakespeare by visiting his house for at least 70 years by then during which time disreputable practises such as visitors being allowed to cut a sliver off relics like the so-called “Shakespeare’s chair” had flourished. It was also possible to arrange a sleepover, spending the night in Shakespeare’s birthroom, breathing in the air which nourished and inspired the poet. During the early nineteenth century there had also been undignified disagreements between one custodian, Mary Hornby and the owner of the property, Mrs Court.

Thomas suggests that Shakespeare’s Birthplace developed in the way it did as a product of the Victorian period with its interest in propriety and class, the terraced cottage turned into a respectable house. Victorian love of domesticity put extra stress on hearth and home, and she reproduces two telling images, both popular in the Victorian period. In one, an idealised Mary Arden tends to her baby son William in his cradle, and in the other, entitled Shakespeare and his family, Shakespeare, the Victorian patriarch, reads aloud from his latest play to his admiring family.

Shakespeare had been called “divine” for many years, so it’s not surprising that when attention shifted to his home it should also be described in religious terms, “hallowed”, ” a place of pilgrimage” and as in the title of the book “a shrine”.

Much of the evidence for this public interest was collected by the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust itself, founded after the purchase of the house. Creating a building and a foundation suitable for the attention of patriotic Englishmen was part of the aim of forming the Trust. As Thomas describes, though, although the house was purchased by public subscription the full amount was not forthcoming, the first of many difficulties over money.

The author suggests that Stratford itself was the invention of the Victorians. Most of the memorials to Shakespeare in the town date back to this period, as did the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre and it was the Shakespeare connection that encouraged the early arrival of railways to Stratford and the growth of the tourist trade with the creation of souvenirs, guide books and postcards.

Such was the interest in Shakespeare that many memorials were suggested, some very amusing. Who knew, for instance, that at one stage in the 1860s there was a plan to create, admittedly in London, a hundred-foot tall metal statue of Shakespeare which would tower over the capital? The building was going to contain attractions on three floors, and visitors to the statue would be able to look out over London through the glass eyes of Shakespeare. It sounds remarkably like the Statue of Liberty, but some decades earlier, and was probably based stories of the ancient Colossus of Rhodes.

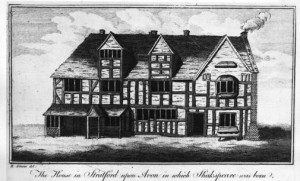

In another chapter she analyses the images of the outside of the building. Before the age of photography when at last the appearance of the building could be verified, images varied according to the artist, publisher and, presumably, what kind of impression they wanted to give, of hovel or gentleman’s residence. The earliest image showing the appearance of the building dates back to the 1750s and the discussions about what was an appropriate method of restoring or preserving the building show that this is not a new subject.

Thomas’s book is densely written, and admirably referenced. Its extensive bibliography demonstrates the depth of her research and she has produced a well-told account of the strange but true story of one of England’s best-known buildings.