In 2010 the British Museum collaborated with the BBC to create The History of the World in 100 Objects, radio broadcasts linked with a website and book of the same name. It focused on items from the Museum’s collection ranging from stone age tools to a solar powered lamp and its legacy lives on: visitors are still encouraged to find the items on display and read their story. It highlighted the power of objects to make connections between ourselves and people from either the far distant past or the other side of the world.

This year the Museum has had the opportunity, or perhaps the challenge, of repeating this formula. But instead of concentrating on historical events they had the difficult task of finding connections between objects and Shakespeare’s ideas, plays and poetry. The twenty objects they picked, and the stories they told, couldn’t just be about social or political history. Material objects certainly help us understand the world in which people lived, what they believed in, and what entertained them, but this isn’t the whole story when you’re looking at someone whose work has had a profound effect of our culture and thinking.

This year the Museum has had the opportunity, or perhaps the challenge, of repeating this formula. But instead of concentrating on historical events they had the difficult task of finding connections between objects and Shakespeare’s ideas, plays and poetry. The twenty objects they picked, and the stories they told, couldn’t just be about social or political history. Material objects certainly help us understand the world in which people lived, what they believed in, and what entertained them, but this isn’t the whole story when you’re looking at someone whose work has had a profound effect of our culture and thinking.

The objects they chose to include in Shakespeare’s Restless World are different: only 7 of the 20 come from the British Museum’s collections, though all feature in the current Shakespeare exhibition. The others have been sourced from a variety of museums, libraries and private collections. They certainly aren’t the “usual suspects”, many of the items being new (at least to me). Some are predictable: a rapier and dagger is linked with both contemporary fashion and gang culture and the plays Hamlet and Romeo and Juliet, and illustrations of the triumphal arches that welcomed James I to London connect him, the emperors of ancient Rome and Shakespeare’s classical plays.

Others are less obvious: the humble woollen cap worn by all ordinary men, referred to in Coriolanus as “stinking greasy caps”, the eye-relic of the Catholic martyr Edward Oldcorne, testament to the brutality of the times with a direct link to the blinding of Gloucester in King Lear.

The objects are carefully chosen and Neil MacGregor has built up complex and fascinating stories around them. Although they were conceived as radio broadcasts and can now be purchased on CD, it’s much easier to take in the detail of each piece by reading the book, not least because of the many colour photographs. MacGregor has the knack of effortlessly linking the item or items with the Elizabethan/Jacobean period, with Shakespeare’s plays, and with modern life.

But the final chapter is an acknowledgement that no matter how skilfully the argument is phrased, objects from his own period can’t explain why Shakespeare has remained both the soul of his own age and of every age since: why Hamlet and Macbeth still speak to anyone suffering under an oppressive political regime, Romeo and Juliet to teenagers everywhere, why people still feel compelled to stage his plays, and audiences continue to go to them.

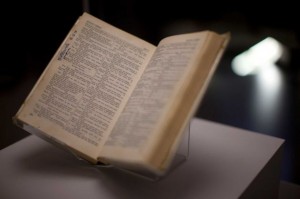

This chapter in the book, as in the exhibition to which it relates, is on the Robben Island Shakespeare. As an object, it’s neither beautiful nor old. But it tells a compelling story about the endurance of the human spirit. Lent by its owner, Sonny Venkatrathnam, this ordinary modern edition of the Complete Works was his only book while he and other members of the African National Congress were incarcerated in the notorious South African jail on Robben Island during the 1970s. The book was passed between these political prisoners, providing them with both recreation and encouragement in their struggle against apartheid. Before his discharge, Sonny got his fellow-activists to sign the book next to their favourite passages. Nelson Mandela’s highlighted quote is from Julius Caesar:

Cowards die many times before their deaths

The valiant never taste of death but once.

Of all the wonders that I yet have heard,

It seems to me most strange that men should fear,

Seeing that death, a necessary end,

Will come when it will come.

It reminds me of another book based on a TV series, Melvyn Bragg’s Twelve Books that Changed the World. The idea was that all the books should be factual: Darwin’s The Origin of Species, for instance. But he too couldn’t miss out Shakespeare’s collected works because Shakespeare represents all the authors whose works of fiction have changed human lives. Bragg quoted Harold Bloom’s statement that the First Folio should be called “secular scripture”.

It would be impossible for this book to explain Shakespeare’s creative achievement. But it does remind us that even in a world superficially so different Shakespeare bridges the divide. The final words of MacGregor’s book sum it up: “Shakespeare’s words console, inspire, illuminate and question. More simply, they capture for us the essence of what it is to be restlessly human in a constantly restless world.”

I don’t know if it’s mentioned in Neil MacGregor’s book, but Shakespeare had a very direct connection with those triumphal arches. On 15th March 1604 Shakespeare is mentioned in the accounts of Sir George Home, master of the great wardrobe as receiving 41/2 yards of red cloth for appearing in the coronation procession of James I with the Kings Men. This must have been the most magnificent piece of street theatre London had witnessed with props and triumphal arches designed by Inigo Jones and small groups of actors creating scenes in honour of James.

Thanks for this reminder of Shakespeare’s connection with this magnificent event!