Earlier this week I attended a day of discussions at the University of Nottingham on Digital Shakespeare, with the subtitle authorship and authority. One of a series of workshops, practitioners and academics were there to share ideas and discuss the directions which future projects might take.

Earlier this week I attended a day of discussions at the University of Nottingham on Digital Shakespeare, with the subtitle authorship and authority. One of a series of workshops, practitioners and academics were there to share ideas and discuss the directions which future projects might take.

Perhaps not surprisingly, my notes taken during the day are almost all questions. What is Shakespearean text? Does the internet change the was we approach Shakespeare, and the way we work in general? And the question with which we started: What do we mean by Digital Shakespeare anyway?

A few years ago, digital Shakespeare largely meant databases, or digitised versions of Shakespeare’s texts, magically searchable. Digitisation made it possible to show onscreen the texts themselves: folios and quartos, plus images of past productions, paintings and book illustrations, plus sound and video recordings. Just in 2010 the journal Shakespeare Quarterly devoted a whole issue to Shakespeare and New Media in which Whitney Anne Trettien, in her article Disciplining Digital Humanities, examined a series of current projects, such as The British Library’s Shakespeare Quartos project and MIT’s Shakespeare performance in Asia. In another article in the same issue, Andrew Murphy compared three open Internet Editions.

In the last few years many things have changed. This week we talked a lot about the blurring of boundaries: digital projects are now much less confined to the large organisations such as the British Library, and are being embraced by a much wider range of smaller partners. The attendees at Nottingham came from diverse backgrounds including universities, libraries, publishers, theatre companies and even an individual (me).

To me the most important effect of digitisation, in particular social media, is the democratisation of learning. Barriers between organisations which have up to now held on tightly to knowledge and amateurs are being broken down. Roberta Pearson suggested that organisations (many of which are funded by the public) must open up and invite fans into “the walled garden”. And in planning projects there’s a need to include people from a wide range of disciplines as well as from different backgrounds and nationalities.

Twitter is an easy tool for amateurs to adopt: Pete Kirwan observed that there are at least 150 people on Twitter calling themselves William Shakespeare. And there are now multiple ways in which people can remodel or rehash Shakespeare’s plays. One of the people present at Nottingham is researching YouTube videos, one of the simplest ways in which individuals can get creative with Shakespeare.

Last year the RSC, as part of the World Shakespeare Festival, launched a digital project called myShakespeare. Sarah Ellis, Digital Producer, was the person behind it as well as the recent Midsummer Night’s Dreaming project. myShakespeare gave people “a place to consider what Shakespeare means to us today. A creative space to share our ideas and thoughts”. You can still see the responses which this project produced, a great shop window for ideas which otherwise would have received much less attention.

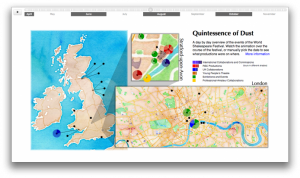

I’ve mentioned several times the Year of Shakespeare website, a place in which to find reviews and information about the many productions of Shakespeare that were part of the World Shakespeare Festival, and encouraged public participation.

Other questions focused on apps: one person present asked why he should want an app when he already has the web. In the Observer last Sunday a new book by Ethan Zuckerman, Rewire: Digital Cosmopolitans in the Age of Connection was reviewed. Zuckerman argues that the internet is actually making us more insular. In the past the mainstream media decided for us what was important and what was not, but no longer. “We’ve built – and use – information tools (such as search and social networking systems) that embody our biases towards things that affect, or are relevant to, those who are nearest and dearest to us. They give us the information we want, but not necessarily the information that we might need”.

Examining the future of digital in the arts is the point of the Digital R&D fund for the Arts, providing resources to “support collaboration between organisations with arts projects, technology providers, and researchers.” The funded projects will enhance audience reach, and results will be disseminated to the wider arts sector”. One of the participants at a forum held in February highlighted the importance of the medium, tweeting that “Many more people may experience our content through social media & blogs than visit our websites”. Here’s a link to one of the projects, based around storytelling and playscripts with a Leeds theatre company.

And an emerging collaboration between Queen Mary College London and the University of Warwick, Global Shakespeare, will be headed from September by Professor David Schalkwyk, formerly Director of Research at the Folger Shakespeare Library, Washington, DC. “Global Shakespeare has been set up to shape the future research agenda in 21st century Shakespeare studies across all platforms including criticism, performance, history, and media from television to digital reproduction.”

I’d like to thank the University of Nottingham, and in particular Roberta Pearson, Kate Rumbold and Peter Kirwan, for their hospitality this week, and all the participants for a stimulating day in the continually-evolving world of Digital Shakespeare.