On 23 December 1631 the poet Michael Drayton died at his lodgings in Fleet Street, London. He was so highly regarded by his contemporaries that he was buried in Westminster Abbey with some ceremony. According to an account of his funeral, which it’s thought was paid for by a patron, “… the Gentlemen of the Four Innes of Court and others of note about the Town, attended his body to Westminster, reaching in order by two and two, from his Lodging almost to Standbridge.”

Ben Jonson’s friend William Drummond of Hawthornden prophesied that Drayton would “live by all likelihead so long as … men speak English.” Yet today few know much about Michael Drayton. He was born in 1563 in Hartshill, near Nuneaton, Warwickshire. Drayton came from a humbler background than Shakespeare, and it seems that when young he was a servant in the household of a noble family. Like Shakespeare, Drayton really became a serious writer when he moved to London. There’s a full biography on the Poetry Foundation site .

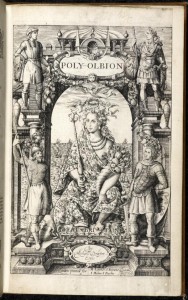

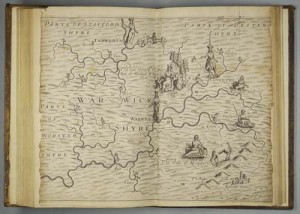

A new project from the University of Exeter is trying to raise the profile of Michael Drayton. It’s called the Poly-Olbion project. Poly-Olbion was his great 15,000-line poem, described on the project website as “an expansive poetic journey through the landscape, history, traditions and customs of early modern England and Wales”. He began this massive poem around 1598. The book is decorated with beautiful allegorical maps by William Hole in which the spirits of the rivers, hills and woods appear as scantily-clad maidens or rustic characters, and with prose “illustrations” by John Selden.

Some of the maps have been scanned and made available by the Folger Shakespeare Library, and some are also on the Windows on Warwickshire site.

The poem was published in two parts, in 1612 and 1622. In just one of many unlucky events in Drayton’s life, the first volume was dedicated to the heir to the throne, Prince Henry who died only months after its publication. The current project aims to produce a scholarly edition of the poem, to hold a conference in 2015, and to publish a volume of critical essays reassessing Drayton’s work. There will also be an exhibition at the Royal Geographical Society, recognising the importance of the poem as a description of the country’s topography as well as its folklore.

Although Drayton lived in London, he is known to have returned to the Warwickshire village of Clifford Chambers, just a couple of miles away from Stratford. In 1622 he wrote a tribute to “his Incomparable Friend, Sir Henry Raynsford Of Clifford” who had died on 27 January 1622, who he described as “so fast a friend, so true a Patriot”. It’s said that he regularly spent summers at Clifford Manor, Raynsford’s home, a building that still stands. From these lines in Poly-Olbion it seems he used the time to write:

‘…dear Clifford’s seat (the place of health and sport)

Which many a time hath been the Muse’s quiet port’

Shakespeare and Drayton are thought to have been friends, and it seems inconceivable that two famous poets would not have met up while both were in the area. One of the legends of Shakespeare’s life is that he died as a result of a night of hard drinking with Ben Jonson and Michael Drayton while both were visiting Warwickshire. Jonson admired Drayton’s work, calling it “pure, and perfect Poesy”. And later John Hall, Shakespeare’s son-in-law, a well-known doctor, records treating Drayton, “an excellent poet”. Particularly in Poly-Olbion Drayton specialised in the description of topographical features, in which Shakespeare took little interest. But there are echoes of Shakespeare’s lines about the native inhabitants of the Forest of Arden in this section:

And near to these our thicks, the wild and frightful herds,

Not hearing other noise but this of chattering birds,

Feed fairly on the lands; both sorts of seasoned deer:

Here walk, the stately red, the freckled fallow there:

The bucks and lusty stages amongst the rascals strewed,

As sometimes gallant spirits amongst the multitude.

Here are a few lines describing the Avon as it flows through south Warwickshire:

Scarce ended they their song, but Avon’s winding stream,

By Warwick, entertains the high complexioned Leam:

And as she thence along to Stratford on doth strain,

Receiveth little Heil the next into her train:

Then taketh in the Stour, the brook, of all the rest

Which that most goodly Vale of Red-Horse loveth best.

These quotations are taken from selections in Roger Pringle’s excellent Poems of Warwickshire.

Travelling between Stratford and Clifford Chambers Drayton, Shakespeare and Hall must have crossed the Avon, perhaps using the little footbridge which from 1590 crossed the Avon at Lucy’s Mill, south of the town itself. It’s still an important crossing point that links lots of paths including those leading to Clifford Chambers. The twentieth century version of this bridge now has a support group aiming to fund a feasibility study to find out if it can be made accessible to people of all ages and abilities. I know I’m digressing, but we’re looking for more supporters and if you’d like to join you can do so on the Friends of Lucy’s Mill Bridge website.

Travelling between Stratford and Clifford Chambers Drayton, Shakespeare and Hall must have crossed the Avon, perhaps using the little footbridge which from 1590 crossed the Avon at Lucy’s Mill, south of the town itself. It’s still an important crossing point that links lots of paths including those leading to Clifford Chambers. The twentieth century version of this bridge now has a support group aiming to fund a feasibility study to find out if it can be made accessible to people of all ages and abilities. I know I’m digressing, but we’re looking for more supporters and if you’d like to join you can do so on the Friends of Lucy’s Mill Bridge website.

When Michael Drayton died he was almost penniless. His pastoral style of poetry, reminscent of Edmund Spenser’s, was no longer fashionable, and Drayton had always preferred to tell the truth as he saw it rather than flattering potential patrons. In a late poem, The Muses Elizium, he prophesied that there would be no future for his kind of poetry. But maybe the project just beginning will bring his work, and the man himself, more attention after so long.