For over 400 years 5 November has been a day of celebration, though it’s now thought of as Bonfire Night with little reference to its origins with the 1605 plot to blow up the King, the Lords and the Commons at the Opening of Parliament. The recent TV documentary Gunpowder 5/11: The Greatest Terror Plot redressed the balance by examining the historical evidence for the plot and brought out the parallels with modern terrorist attacks based on religious extremism such as 9/11. The programme is available on BBC IPlayer until the middle of November 2014.

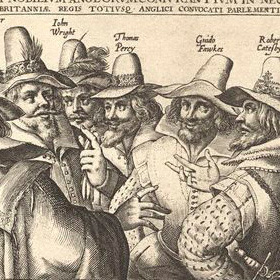

Dramatised scenes used the actual words of Thomas Wintour and Guy Fawkes taken from records of their interrogations after their capture, but thankfully didn’t replicate the torture and execution of the conspirators. The plot was the most ambitious political conspiracy at a time when threats against the monarch were not uncommon, and if it had succeeded the effects on the whole country would have been profound. Based on a planned explosion in London it is usually forgotten that the plot was hatched in the Midlands, not far from Shakespeare’s Stratford. After its failure, the plotters, other than Guy Fawkes who was captured on the spot, escaped, passing through the Midlands to regroup at Holbeache in Staffordshire where the final showdown was held just three days later.

There is a lot of information on the UK Parliament website, and I find there is even a Gunpowder Plot Society. Scotland’s History website also includes lots of links on the subject of the plot.

Towards the end of 1605 the Thanksgiving Act was passed. Under its provisions special church services were held commemorating the failure of the plot, that continued to be observed every 5 November for two centuries.

As a result of the plot English Catholics, already persecuted, continued to suffer. In his 2012 book Shakespeare’s Restless World, now reissued in paperback, British Museum Director Neil MacGregor uses artefacts to highlight aspects of contemporary life that also surface in Shakespeare’s plays. In Chapter 11, Treason and Plot, he chooses a book which lists the many plots that threatened the crown. The Thankfull Remembrance of God’s Mercie, compiled by George Carleton, Bishop of Chichester, was a catalogue of all the plots that had threatened England since the beginning of Elizabeth’s reign up to 1624 when the book was published. MacGregor notes “In eighteen chapters he frightens and thrills his readers with fifty years of conspiracies, intrigues and assassination attempts.” Almost always, the perpetrators were accused of being Catholic, often foreign.

In MacGregor’s chapter on Carleton’s book he quotes academic Susan Doran “There was an anxiety – almost like Islamophobia today, or at least as it was at the time of the Twin Towers – that there was an international conspiracy to overturn Protestantism, the true church, as well as the true monarch”. One of the most disturbing elements of the Gunpowder Plot was that the conspirators were all British, another link with recent terrorist threats in the UK.

As usual when he was writing about politically sensitive subjects, Shakespeare doesn’t tackle real plots directly, but addresses threats to rulers’ lives in plays set reassuringly in the past including Julius Caesar, most of the English history plays and Macbeth. Macduff is given the job of explaining the significance of King Duncan’s murder in Macbeth:

Confusion now hath made his masterpiece!

Most sacrilegious murder hath broke ope

The Lord’s anointed temple, and stole thence

The life o’ the building!

Exactly the same thing could have been said had the Gunpowder Plot succeeded.

In another chapter of Neil MacGregor’s book he looks at an object which, like Shakespeare’s plays, turns out to be not quite what it seems. It’s a model of a ship, but it is not just a toy or decorative piece. It is what’s known as a votive ship, “offered to churches in thanksgiving,…rare in Britain…but…very common in Denmark, where around 1300 examples are still known”. It dates from 1590 when the young King of Scotland, to become James 1 of England some years later, and the Princess of Denmark were married after a particularly stormy voyage. MacGregor notes that Scottish witches were more dangerous than their English counterparts “Trying to sink the King’s ship is exactly what you would expect a Scottish witch to do”. At the infamous trials of witches in North Berwick women were accused of exactly this crime and one, Agnes Sampson, was convicted and executed.

Both these artefacts, the book and the model ship, demonstrate how real the threats of witchcraft, Catholicism and assassination were. In its twenty well-chosen objects Shakespeare’s Restless World offers an unusual, fascinating way of looking at the world in which Shakespeare lived and which formed the backdrop to his writing.

Great post Sylvia! Picking up on the witchraft link I like this quote from William Perkins wrote in his Discourse of the Damned Art of Witchcraft (1616-1618):

“It is a principle of the Law of Nature, holden for a grounded truth in all countries and kingdoms that the traytor who is an enemy to the State and rebelleth against his lawful prince, should be put to death, now the most notorious traytor and rebel that can be is the witch. For she renounceth God himselfe, the King of Kings, she leaves the society of his church and people, she bindeth herself in league with the devil.”

A clear statement of the fact that if you rebel against the King you’re basically in league with the Devil! Shakespeare’s first tetralogy focuses on a number of such politically imbedded witchcraft cases: Joan of Arc, Eleanor, Duchess of Gloucester, Margery Jourdain, Margaret, Queen Elizabeth and Jane Shore. They are all accused, and some of them convicted of witchcraft in order to thwart their claims to power.