Picture the Elizabethan period and the chances are you will think of portraits, probably one of those dazzling paintings of Queen Elizabeth herself. There are so many, so well-known, they have individual names: the Armada portrait, the Hardwick portrait, the Pelican portrait, the Rainbow portrait and the Darnley portrait are just some of the most famous. But what makes them impressive is not the rather expressionless face of the woman portrayed, but the clothes she is wearing.

Elizabeth was said to have 3000 gowns, many of them embroidered and covered in jewels. They were popular gifts to the Queen from her loyal subjects, and costumes were more than adornments, representing the power of the monarch and the aspirations of the state. The more elaborate and valuable the better. Elizabeth’s interest in costume spread to her courtiers, and from them down to ordinary people.

A small army of skilled seamstresses and tailors must have been employed in creating gorgeous costumes, with more and more people buying elaborate clothes simply because they could afford to. But with people lower down the social scale able to wear clothes formerly only available to the nobility there was a fear of disruption and division.

And during Elizabeth’s reign the idea of fashion, with constantly changing designs, really established itself. I’ve found Sarah Jane Downing’s Fashion in the Time of William Shakespeare a thought-provoking and well-illustrated introduction to the subject. As well as images, she uses many quotations from contemporary writings to demonstrate how controversial clothes could be.

And during Elizabeth’s reign the idea of fashion, with constantly changing designs, really established itself. I’ve found Sarah Jane Downing’s Fashion in the Time of William Shakespeare a thought-provoking and well-illustrated introduction to the subject. As well as images, she uses many quotations from contemporary writings to demonstrate how controversial clothes could be.

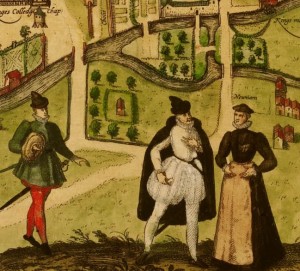

A number of concerns led to the re-enforcing of the Sumptuary Laws from earlier in the century. These laid down rules for who could wear what sort of clothes, and who could carry weapons. One motive was to protect the English wool trade: Sarah Jane Downing has a whole chapter on wool. As a result of the importation of foreign fabrics “the manifest decay of the whole realm generally is likely to follow” because of the “superfluity of silks, cloths of gold, silver, and other most vain devices”. There was also a worry that “the meaner sort” were spending more than they could afford.

But there was also an element of keeping the lower orders in their place with only some people entitled to wear the most expensive items. “All degrees above viscounts, and viscounts, barons, and other persons of like degree” were allowed to wear such exotic fabrics as “Cloth of gold, silver, tinseled satin, silk, or cloth mixed or embroidered with any gold or silver”, and there were different rules for how they could be used. Purple silk was restricted, as was crimson or scarlet velvet, fur, and pearls. Gold trimmings were allowed on the hats and garters of those attending on the Queen. The restrictions were complicated and the Sumptuary Laws were designed to be voluntary rather than strictly enforced, which meant that they were regularly broken.

The English were obviously receptive to the idea that costumes would need updating frequently. Writing in the 1580s William Harrison was exasperated by his fellow-Englishmen’s desire for novelty: “and as these fashions are diverse, so likewise it is a world to see the costliness and the curiosity, the excess and the vanity, the pomp and the bravery, the change and the variety, and finally, the fickleness and the folly that is in all degrees, insomuch that nothing is more constant in England than inconstancy of attire”.

Shakespeare’s comments suggest that he was amused by fashion rather than a follower of it. In The Taming of the Shrew much is made of the creation of a new cap for Katharine by one of what Harrison called “fickle-headed tailors”. In The Winter’s Tale Autolycus describes the items he has to sell at the sheep-shearing:

Lawn as white as driven snow;

Cyprus black as e’er was crow;

Gloves as sweet as damask roses;

Masks for faces and for noses;

Bugle bracelet, necklace amber,

Perfume for a lady’s chamber;

Golden quoifs and stomachers,

For my lads to give their dears.

In The Tempest Prospero orders Ariel to fetch his “trumpery” as bait “to catch these thieves”. To Caliban’s distress, Stephano and Trinculo are easily distracted from their plan to kill Prospero by the chance to try on some fine clothes. The ridiculousness of fashion is exploited in Twelfth Night where Malvolio is tricked into appearing before Olivia wearing cross-gartered stockings, “a fashion she abhors”.

As Polonius had it, “the apparel oft proclaims the man”, and William Harrison made an exception to his criticism of levity and fickleness for merchants, “albeit that which they wear be very fine and costly, yet in form and colour it representeth a great piece of the ancient gravity appertaining to citizens and burgesses”.

Sarah-Jane Downing explores the development of many kinds of clothing including the different styles of farthingales, jerkins and doublets. The book also contains many examples of that most characteristic of Elizabethan garments, the ruff. They were one of the few garments worn by both men and women, and even children. They were also worn by most levels of society, though they must have been troublesome to wear and difficult to clean and maintain. Those worn by nobility reached huge sizes and were beautifully-decorated.

People still seem to be obsessed with ruffs. Here’s a history of the ruff, with some lovely pictures. This blog is all about collars, with references to ruffs. And this website even shows you how to make one for yourself.