Standing on the aptly-named Swallow Point, a promontory overlooking the Bristol Channel a week or so ago with some local birdwatchers, I was reminded what an exciting time this is for wildlife. They noted how many of the birds flying over were migrating from their wintering grounds to wherever they would be nesting and bringing up a family before, in late summer, making the return journey. Sand martins flew above our heads, and whimbrel waded on the shore. The Severn Estuary and many rivers are signposts guiding birds in from the Atlantic to their summer homes.

Migration has been going on for thousands of years, but most of us now don’t really notice it. Shakespeare was aware that birds came and went: he noted that daffodils flowered “before the swallows dare”, and although he knew of this annual cycle, he wouldn’t have known where they went. It’s only in the last few decades that it’s been possible to track birds as they migrate, finding that swallows fly each winter all the way to Africa.

My husband used to be in charge at Mary Arden’s House in Wilmcote, the home of Shakespeare’s mother, and would note in the diary the day on which the swallows returned, always to the same place. It’s amazing to think that swallows have probably been doing this, coming back to nest in the same barns, since Shakespeare’s time, and people must have found it an exciting moment when the birds arrived back, a time to celebrate “the sweet o’the year”. According to the diaries they most often arrive in Wilmcote between 10 and 14 April, though the date has varied between 3 and 23 April depending on the weather and wind direction.

Even birds that we think are “ours”, may not be. We see starlings all year round, but some birds winter here having migrated from Russia to the UK’s relatively mild climate, while some of the birds that have brought up their families in the midlands in the summer might migrate further south in the winter.

In our garden a blackbird, nesting in a thick bush next door, has been singing loudly and tunefully. Blackbirds also migrate, so our cheery neighbour might well have spent the winter further south. Shakespeare calls the blackbird by its traditional name, the ouzel-cock, in the song which Bottom sings to show he is not afraid when he is left alone in the wood at night in A Midsummer Night’s Dream:

The ousel cock so black of hue,

With orange-tawny bill,

The throstle with his note so true,

The wren with little quill,

The finch, the sparrow and the lark,

The plain-song cuckoo gray,

Whose note full many a man doth mark,

And dares not answer nay;

All these birds are still found in the midlands. This name for the blackbird is recalled in the name of the ring-ouzel, only found in rocky areas, the male of which is similar to a blackbird but with a white bib.

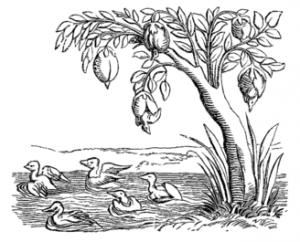

A less-common bird owes its name to the mysteries of migration. Barnacle geese are now known to breed in the arctic, wintering on the coast of Britain and North-west Europe. In the British Isles, then, they are never seen nesting, or as juveniles. The myth grew up that the geese did not hatch from an egg in the usual way. John Gerard’s 1597 Herball, or Generall Historie of Plantes, includes a long section “Of the Goose tree, Barnacle tree, or the tree bearing Geese”. “There are found in the North parts of Scotland…, certaine trees wheron do grow certaine shells…wherein are contained little living creatures: which shells in time of maturity doe open, and out of them grow those little living things, which falling into the water do become fowles, which we call Barnacles”.

Gerard claims to have seen how the barnacle shells that were washed ashore attached to driftwood developed with his own eyes. This is supposed to have taken place in Lancashire: he calls it “one of the marvels of this land”. “When it is perfectly formed the shell gapeth open, and the first thing that appeareth is the fore-said lace or string; next come the legs of the bird hanging out, and as it groweth greater it openeth the shell by degrees, til at length it is all come forth…and falleth into the sea…where it gathereth feathers, and groweth to a foule.”

Gerard is clearly aware that many would be unconvinced that trees could produce living birds, but there was no evidence to contradict it. How else could the sudden appearance of the adult birds in the summer be explained? The idea that birds could fly thousands of miles twice a year would probably have been seen as equally unlikely. It’s a great example of how stories were made up to explain the mysteries of the natural world before scientific theories based on evidence were developed.

If you would like to hear the beautiful sounds of British wildlife, in particular “the sweet birds”, you can listen to some of the British Library’s British Wildlife recordings here.

Smashing – loving your ‘spring series’.

The ‘ousel-cock’……..you learn something new every day.

Thanks for your comments JW!