The Radio 4 Book of the Week beginning on 4 May 2015 was Antony Sher’s Year of the Fat Knight: the Falstaff Diaries, his account of the process of preparing for and performing Falstaff in Henry IV parts 1 and 2 for the RSC in 2014. Antony Sher is a remarkably creative and imaginative man: he draws and paints, often showing himself in many of his roles, he writes beautifully, both books about himself and novels, and is of course a charismatic performer on stage, TV and film. It’s something of a relief to read in Stanley Wells’ new book Great Shakespearean Actors that he does have a weakness: he is tone-deaf.

Wells’s book lists many of Sher’s most famous roles: Lear’s Fool, his first role with the RSC in 1982, almost stole the show from Michael Gambon. It was followed by the role with which he’s most closely associated, Richard III. Richard is showy and theatrical but doesn’t require psychological subtlety. I saw an early preview and was sitting towards he side, near the front of the stalls (in the days when these were relatively cheap). As he delivered his first speech I still remember the shock of him bringing his crutches forward from behind him and charging downstage, intimidating us at the same time as taking us uneasily into his confidence.

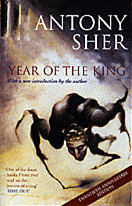

Following the success of this performance he published Year of the King, that explains in tremendous detail how he approaches a role, and included many of the sketches he did during rehearsal, self-portraits that show how the part developed in his mind. Later on his theatricality didn’t always work so well. In his essay about Sher, Wells provides an analogy with music: “In acting, as in musical performance, virtuosity can be the enemy of spontaneity. The self-consciously studied nature of Sher’s art which reflects the acute intelligence and deep thoughtfulness with which he prepares his roles means that for some spectators the artifice of the playing can seem too close to the surface.” His collection of essays on his top forty actors is always perceptive, and the eleven-page introduction, worth reading in its own right, is available from the OUP site.

I loved the wild anarchy of his hilariously funny performance as Tartfuffe at the Pit in London, but my favourite among his Shakespeare roles was Leontes in The Winter’s Tale, in which I thought he did abandon the self-consciousness Wells mentions. Many reviewers agreed. John Peter described it as “one of Sher’s most intense, most fully achieved performances” and Michael Billington found “he is at his best when he surrenders to the emotion of the moment heartbreakingly so in the final act”.

Since then there have been other successes, notably an African Tempest in which he played Prospero, but we’re told in his new book that he had never contemplated playing Falstaff until he was suggested by fellow-actor Ian McKellen. As well as mapping the day by day process of approaching the role, Sher is remarkably frank about himself, talking openly about the time when he was addicted to cocaine (fortunately long past), and about his distress at Nelson Mandela’s death that occurred while he was preparing to play Falstaff.

He admits to having had difficulty learning lines now he’s in his sixties, but writes eloquently about how for actors the words become physical:

To an actor, dialogue is like food. You hold it in your mouth, you taste it. If it’s good dialogue, the taste will be distinctive. If it’s Shakespeare, the taste will be Michelin-starred. Falstaff’s dialogue is immediately delicious. You’re munching on a very rich pudding indeed, probably not good for your health, but irresistible.

He’s well-educated and he’s a thief, a highwayman. A gentleman-rogue, then. That breed of privileged, public-school Englishman who can be both monstrous and charming, both powerful and self-destructive, the kind that believe the world belongs to them. They can break the law, it’s only a bit of fun. they can drink themselves senseless, it’s what chaps do. And they’d be totally at ease hanging out with the future king. “I’ll teach him a thing or two”. This country is full of people like that. Maybe that’s why Falstaff is so loved. He’s so familiar.

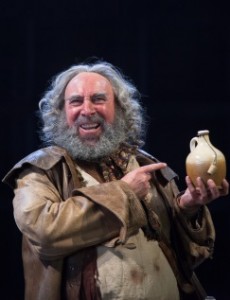

This sounds as if Sher had little sympathy for Falstaff during rehearsals, but in performance he found the man’s humanity. The Evening Standard described him as “irrepressible … a lord of misrule who’s absurd, delightful and in the end deeply sad”. The Guardian warned “just as you start to warm to this Falstaff, you are reminded of his rapacity”. Sher successfully conveyed his contradictions, winning the Critics Circle Award for Best Shakespearean Performance. Sher acknowledges that it is a great role: “Just like there are wonders of nature, there are wonders of art and the creation of Falstaff is one of them”.

The Year of the Fat Knight is illustrated with his own sketches and paintings, and the BBC includes a gallery of images to complement the readings. Sher’s five recordings are available to listen to for the rest of May 2015 and if you’re not able to get these, the book is a very good read!

Thanks for the notification, I just finished listening to the programme on BBC Radio 4, excellent.