I’m writing this post on the day of the General Election, 7 May 2015, and by the time you read it most of the results will be in. All the indications are that there will be no clear winner, leading to another coalition government. It’s even possible that there won’t be a formal coalition so parties will have to tread carefully, negotiating on each vote.

It’s a far cry from Shakespeare’s day when only a small elite had any say over how the country was governed, the monarch holding ultimate power. In some respects, though, things were not so different. Anyone wanting to get into power had to tread carefully, as courtiers could find that a single mistake led to the destruction of their reputations or their royal favour.

Shakespeare often wrote about the fragility of power and reputation, and Sonnet 25 in particular focuses on it:

Let those who are in favour with their stars

Of public honour and proud titles boast,

Whilst I, whom fortune of such triumph bars

Unlook’d for joy in that I honour most.

Great princes’ favourites their fair leaves spread

But as the marigold at the sun’s eye,

And in themselves their pride lies buried,

For at a frown they in their glory die.

The painful warrior famoused for fight,

After a thousand victories once foiled,

Is from the book of honour razed quite,

And all the rest forgot for which he toiled:

Then happy I, that love and am beloved,

Where I may not remove nor be removed.

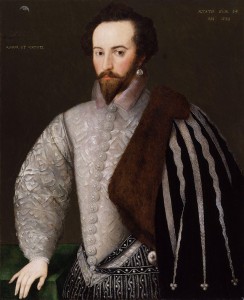

In his copy of the Sonnets my father noted that he had heard Ben Kingsley speak it in a radio programme. The note also includes the word “Ralegh” and a question mark. Presumably it was suggested that the “painful warrier” was Sir Walter Ralegh, a man who epitomised the fate of the courtier, his reputation ebbing and flowing during Elizabeth’s reign, then executed under James 1 after a long imprisonment.

I’ve recently been enjoying Mathew Lyons’ book The Favourite: Ralegh and his Queen. Queen Elizabeth’s long relationship with Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester is well-documented, as is her shorter relationship with the Earl of Essex that ended with his execution. Matthew Lyons’ book spells out the way in which Elizabeth exerted control over many young men by favouring them, playing themselves off against each other. Even during the years when Dudley was dominant there were other favourites like Christopher Hatton, and Ralegh’s rise coincided with Dudley’s marriage that ended his closeness to the Queen. Ralegh’s chance came in 1581 when he, no doubt to everyone’s surprise, enjoyed military success. Lyons comments “Not many English captains returned to court from Ireland with their reputation enhanced and the swagger of a clearly defined victory in their gait”.

Ralegh is one of those figures around whom legends gathered. He probably didn’t bring back tobacco and potatoes from the new world (probably untrue), but it’s possible that at this critical time, according to Fuller’s Worthies of England, he did lay his cloak beneath Elizabeth’s feet in a dashing gesture:

This captain Ralegh coming out of Ireland to the English court in good habit (his clothes being then a considerable part of his estate) found the queen walking, till, meeting with a plashy place, she seemed to scruple going thereon. Presently Ralegh cast and spread his new plush cloak on the ground; whereon the queen trod gently, rewarding him afterwards with many suits, for his so free and seasonable tender of so fair a foot cloth.

Ralegh had shown himself useful in Ireland, and some of his voyages of exploration resulted in riches going into the royal coffers. In 1587-8 he contributed greatly to the preparations for challenging the Spanish Armada. Personally Ralegh was not well-liked, but the plain speaking that made him unpopular with some was liked by the Queen. According to Lyons again, his “riveting matter-of-fact directness …contrasted violently with the deferential, self-defensive tone of much court discourse”. No politician then.

No wonder Sonnet 25 has been thought to refer to Ralegh, whose favoured status and achievements in war and foreign policy could not protect him from the displeasure of the monarch. He was, though, hardly alone, most of those who had been Elizabeth’s favourites falling out of favour. Leicester and Essex are just two of them: Francis Drake was also disgraced, and the Earl of Southampton was imprisoned in the Tower. It seems more likely that Shakespeare was making a general comment about the dangers of being in the public eye, and examples could be found in the books he used as sources for his plays. The fate of “the painful warrior famoused for fight” who loses his reputation even “after a thousand victories” is reminiscent of what happens to the Roman warrior Coriolanus, a story Shakespeare found in Plutarch’s Lives of the Noble Greeks and Romans.

Many others lose their reputations, or even their heads: Cassio in Othello is disgraced by a drunken brawl, and many of the one-time followers of Richard III are executed during the play of the same name.

Just as in Shakespeare’s day, political careers may well be on the line today. The electorate may have spoken, but in the aftermath of the election Ralegh may well be proved right: “In all that ever I observed in the course of wordly things, I ever found that men’s fortunes are oftener made by their tongues than by their virtues”.