At the end of the growing season the shops are full of produce, with onions, pumpkins and other vegetables in store for the winter. As the harvest hymn has it, “all is safely gathered in /ere the winter storms begin”.

At the end of the growing season the shops are full of produce, with onions, pumpkins and other vegetables in store for the winter. As the harvest hymn has it, “all is safely gathered in /ere the winter storms begin”.

In a lovely little book celebrating the Bodleian Library’s own sumptuous copy of John Gerard’s 1597 Herball, Margaret Willes links some of the plants he describes to Shakespeare’s own mentions. Many are to The Merry Wives of Windsor, where vegetable references are in great abundance. In fact in another book Rebecca Laroche’s essay: “Cabbage and roots” and the difference of Merry Wives” forms a whole chapter in The Merry Wives of Windsor: New Critical essays edited by Evelyn Gajowski and Phyllis Rackin.

These references fit perfectly into the play’s middle-class domestic setting, full of the minutiae of everyday life including doing the washing and gossiping about the latest romances. Margaret Willes picks many of them up: Falstaff’s “Good worts? Good cabbage!” arises because of a misunderstanding caused by Sir Hugh Evans’s Welsh accent. The wives decide to get their own back on Falstaff who they describe as an “unwholesome humidity, this gross watery pumpkin”. Looking forward to a romantic assignation Falstaff exclaims “Let the sky rain potatoes, let it thunder to the tune of Greensleeves, hail kissing-comfits, and snow eringoes”. And faced with the prospect of marrying Doctor Caius, Anne Page would “rather be set quick in the earth/ And bowled to death with turnips”.

Rebecca Laroche, again, notes that “The vegetables of Merry Wives are scattered throughout the play…They are invoked as puns and metaphors, but never directly as food being eaten”. Everyday vegetables are named alongside more exotic recent imports: “The commonness of cabbage and roots contributed to an intimate way of knowing, which is then juxtaposed to and foiled against the otherworldly and new worldly potatoes and pumpkins.”

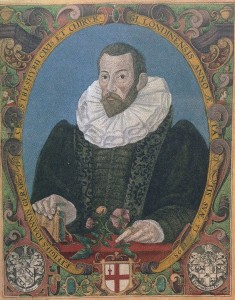

Willes’s book is illustrated with the coloured illustrations from the Bodleian’s copy, including the delightful image of Gerard himself holding the plant with which he was most closely associated, a potato plant from Virginia. Falstaff’s excitement over the plant is because this exotic and rare import was thought to be an aphrodisiac.

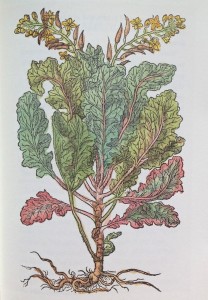

Other plants like cabbages were more ordinary, but Gerard included the illustration and description anyway. His Garden Colewoort is more like what we would call spring cabbage, all leaf and no heart, but Gerard includes several different types as well as the Cauliflower. Culpepper, in his Complete Herbal, can barely be bothered to describe cabbages and coleworts ,”they being generally so well known that descriptions are altogether needless.”. He went to town though on the effects of eating them: “boiled gently in broth”: being taken with honey, it recovereth hoarseness or loss of the voice: the often eating of them, well boiled, helpeth those that are entering into a consumption: the pulp of the middle ribs of colewort, boiled in almond milk, and made up into an electuary with honey, being taken often, is very profitable for those that are pursy or short-winded; being boiled twice and an old cock boiled in the broth, and drunk, helpeth the pains and the obstructions of the liver and spleen, and the stone in the kidneys; the juice boiled with honey, and dropped into the corner of the eyes, cleareth the sight, by consuming any film or cloud beginning to dim it”. He carries on in this vein for quite some time.

Cabbages, or cole worts, were a staple of the cottager’s diet, being cooked up to form pottage. Perhaps Culpeper was trying to persuade the well-off that this humble food was a valuable addition to a rich diet: one of its benefits was that it helped to treat gout. Willes quotes another genteel writer, Elinor Fettiplace, who reminded her readers of the importance of thinking ahead to next season by sowing cabbages even at this darkening time of year.

Sow red Cabage seed after Allhallowentide [1 November], twoe dayes after the moone is at the full, & in March tiake up the plants & set from fowre foot each from other, you shall have faire Cabages for the Sumer; then sow some Cabage seeds a day after the full moone in Marche, then remove your plants about Midsomer, & they wilbee good for winter“.

The poet Michael Drayton remembered that everything has its season and its place. His great poem describing Britain, Poly-Olbion, also describes the humble veg grown here:

The Cole-wort, Cauliflower, and Cabbage, in their season,

The Rouncefall, great beans, and early ripening peason:

The Onion, Scallion, Leek, which housewives highly rate;

Their kinsmen Garlic then, the poor man’s Mithridate;

The savoury Parsnip next, and Carrot pleasing food;

The Skirret (which some way) in sallats stirs the blood;

The Turnip, tasting well to clowns in winter weather.

Thus in our verse we pott, roots, herbs, and fruits together.

The great moist Pumpkin (pumpion) then that on the ground doth lie,

A purer of his kind, the sweet Muskmullion by;

Which dainty palates now, because they would not want,

Have kindly learned to set, as yearly to transplant.

I trust that Ms. Willes gives due credit to……..

‘Folklore of Shakespeare’ by T.F. Thistelton-Dyer – London – Griffin & Farran – 1883