In the mid nineteenth-century a group of young artists joined together with the aim of challenging the practices of the Royal Academy, wishing to paint serious subjects using the art of the middle ages and great works of literature as inspiration. Their intention was to be faithful to nature and to paint outdoors. They called themselves the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, and Shakespeare’s plays offered ideal subject matter. Not only does Shakespeare describe beautiful natural scenes, but he writes scenes which of emotional and moral complexity. The initial group included names that became famous: John Everett Millais, Dante Gabriel Rossetti and William Holman Hunt. Just a few years after the group founded in 1848 it began to evolve, with some members finding new directions to go in while younger artists such as Edward Burne-Jones and William Morris joined.

Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery has a brilliant collection of Pre-Raphaelite paintings, and has recently opened an exhibition entitled Enchanted Dreams, focusing on the work of another late arrival, Edward Robert Hughes. From 1888 Hughes was William Holman Hunt’s studio assistant as well as being an artist in his own right and in this exhibition the Gallery celebrates Hughes’ achievement in the context of the whole Pre-Raphaelite movement. It runs until 21 February 2016.

As well as mounting this exhibition to bring attention to its Pre-Raphaelite holdings, BMAG maintains a number of online resources including a podcast series and an online image database that gives access to many of the sketches and preliminary works which they are not able to display.

The most famous of all paintings of a Shakespearian subject is Millais’ glorious Ophelia, at the Tate Gallery. With its serious subject it’s perhaps an unlikely favourite, but Millais’s sumptuous treatment of the plants on the river bank, painted in beautiful jewel-like colours is at least partly responsible for its popularity, along with the portrait of a beautiful young woman. The story of how the model, Lizzie Siddal, nearly died while the painting was being created, has also contributed to this painting’s reputation.

Millais also devoted a huge amount of time to painting Ferdinand lured by Ariel, from The Tempest. Now in a collection in Washington DC the painting is a strange composition with the figure of Ferdinand listening with great concentration to Ariel, described by a critic as “a hideous green gnome”, with his attendant fairies, who are singing “Full Fathom Five”, a song about the drowning of his father. Millais painted it in the summer of 1849 while staying near Oxford. He wrote to Holman Hunt that it was “ridiculously elaborate. I think you will find it very minute, yet not near enough so for nature. To paint it as it ought to be would take me a month a weed – as it is, I have done every blade of grass and leaf distinct”.

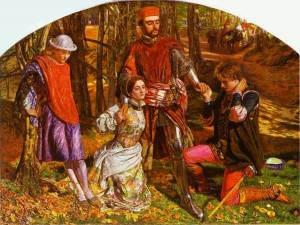

Both of these paintings by Millais conjure up a mood and a place rather than illustrating a particularly dramatic moments from Shakespeare’s plays. One of the greatest of Shakespeare paintings that does just that hangs at BMAG where it can be freely seen. It’s William Holman Hunt’s painting of the final scene of The Two Gentlemen of Verona, Valentine rescuing Silvia from Proteus. This too is gorgeously painted in richly glowing autumn colours. To paint the woodland background he spent several weeks at Knole in Kent before beginning on the figures.

Hunt chose to illustrate the highly-charged moment at which the complex plot reaches its climax. In the book Shakespeare in Art, John Christian describes it: “Valentine, banished from Milan for paying court to the duke’s daughter, Silvia, has just saved his lover from being raped by his false friend Proteus, whose machinations have already led to Valentine’s banishment. Proteus, his treachery revealed, is overcome by guilt and remorse, while on the left his first love, Julia, who has followed him to Milan from Verona disguised as a page, looks on with dismay as Valentine not only assures him of his continued friendship but offers to resign Silvia to him as well”.

He continues: “lust, betrayal, shame, generosity, innocence, unrequited love and sexual jealousy all play a part”. I’m not sure that all that would be conveyed to anyone coming to the painting without knowing the story, but Hunt certainly conveys the emotion of the moment, each of the four responding quite separately to what is happening. It is a glorious piece of work: Ford Madox Brown described it as “without fault and beautiful to its minutest detail”.

So what about Edward Robert Hughes and Shakespeare? Well his painting Midsummer Eve certainly owes something to Shakespeare’s depiction of Titania and her fairies, and there is a dream-like, imaginative quality to much of his work such as Night with her Train of Stars that is reminiscent of the magical world of A Midsummer Night’s Dream. More prosaically, Wikipedia includes a painting of his showing Katherina from The Taming of the Shrew in pensive mood after she has been left with no food by Petruchio. The painter leaves us asking: how she will react to this dilemma?

I am looking forward to visiting the exhibition; thank you for background information re Shakespeare.