It’s become a tradition now for the Shakespeare Institute in Stratford-upon-Avon to spend most of June reading the surviving works of writers contemporary with Shakespeare. In 2018, beginning on 11 June, it’s the turn of Philip Massinger, one of the less well-known of them. His plays are rarely staged, but academics have given them more attention.

Massinger was born in 1583 and as the Institute’s site notes, “he began to write plays at around the time Shakespeare retired, and by the end of the decade he was acknowledged as a technical master of the art. He was also one of the most politically and constitutionally engaged dramatists in a period of deepening crisis in England; with their trenchant critiques of landed wealth, official corruption, and inappropriate government policies, his plays frequently ran into censorship difficulties.”

Massinger’s another of those writers who collaborated with many different people in order to create plays for the stage and it’s thought that he wrote part of around fifty plays. He worked particularly closely with John Fletcher. The Globe has a description of his career:

“Thanks to payment for his plays, pensions and gifts from his patrons, Massinger became prosperous. In the early 1620s, he began establishing himself as an independent playwright for the Lady Elizabeth’s Men at the Cockpit, for whom he wrote his romantic tragicomedies The Maid of Honour, The Bondman and The Renegado. But Massinger’s main theatrical association was with the King’s Men at the Globe and the Blackfriars, succeeding Fletcher as their ‘house dramatist’ in 1625. Massinger’s first play for the King’s Men was the complex tragedy The Roman Actor, which Massinger called the ‘most perfit birth of my Minerva’ (the Roman goddess of wisdom). Massinger’s contemporary Sir Thomas Jay praised his A New Way to Pay Old Debts – possibly Massinger’s best play – for ‘the sweet expressions, got neither by theft, nor violence; the conceit fresh, and unsullied.’

A New Way to Pay Old Debts, surprisingly, was one of the most popular plays of the early nineteenth century. The famously intense actor Edmund Kean discovered in the leading character, Sir Giles Overreach, an ideal vehicle for his talents. Kean’s Richard III was renowned, and he made this role “a Richard III of common life”. In his hands the play, probably never a particularly funny comedy, became a melodrama. Overreach is a wealthy man who tries to buy his way into the aristocracy, using a combination of explosive rage and threats of violence. Kean’s interpretation was called “the most terrific exhibition of human passion” ever seen on stage. In the end, though, he is defeated by the members of the upper class which he aspires to join, and loses his mind.

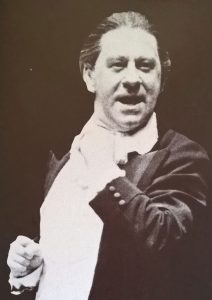

The play was staged by the RSC in 1983 at its studio theatre The Other Place in a wonderfully-cast production which featured Emrys James in the leading role. James never became a household name but he was a powerful stage actor and ideally suited to the role. Irving Wardle wrote “He begins as a classic image of the wicked squire; but as soon as the intrigue gets under way he outdoes the surrounding menagerie in grotesque behaviour…his face working through a malevolent bestiary from snarling dog to smiling crocodile…When he finally goes mad, he caps a bedlam shriek with a still terribly lucid monologue”. The production, directed by Adrian Noble, was criticised as a “grotesque pantomime” and a “nightmare children’s party”, though I remember enjoying it enormously, in particular Emrys James’s performance.

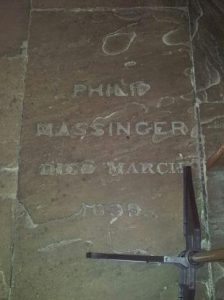

Massinger died in March 1640 during the build-up to the Civil War. He was buried in St Saviour’s, Southwark, now Southwark Cathedral. He is said to have been buried in the same grave as John Fletcher. A slab is in the Cathedral but this was probably put in place during the nineteenth-century renovations. At the same time stained glass windows were installed, dedicated to a number of famous people associated with the church. These included Shakespeare and Alleyn as well as Massinger, but all were destroyed in 1941 as a result of wartime bombing. In 1954 a brand new window to Shakespeare was created, but not, sadly, those to other people of note.

There’s a lot of information about the history of the church here.

If you wish to join in, you’re welcome but if you’re not already known to the Institute you should contact the organizer, Dr Martin Wiggins (m.j.wiggins@bham.ac.uk).

The website giving all the details is here. Incidentally the website also includes links to online texts of the plays, and anyone wanting to tweet about the session should use the hashtag #massimara.

The full timetable is also reproduced below.

Week 1

Monday 11 June

10.30: The Honest Man’s Fortune

2.30: Love’s Cure

7.00: Beggars’ Bush

Tuesday 12 June

2.30: The Queen of Corinth

7.00: Rollo

Wednesday 13 June

10.30: Thierry and Theodoret

2.30: The Elder Brother

Thursday 14 June

2.30: The Knight of Malta

7.00: The Fatal Dowry

Friday 15 June

10.30: Sir John van Oldenbarnevelt

2.30: The Custom of the Country

Saturday 16 June

10.30: The Laws of Candy

2.30: The Little French Lawyer

Week 2

Monday 18 June

10.30: The False One

2.30: The Virgin Martyr

7.00: The Duke of Milan

Tuesday 19 June

2.30: The Double Marriage

7.00: The Prophetess

Wednesday 20 June

10.30: The Sea Voyage

2.30: The Spanish Curate

Thursday 21 June

2.30: A Very Woman

7.00: The Bondman

Friday 22 June

10.30: The Renegado

2.30: The Parliament of Love

Saturday 23 June

10.30: The Fair Maid of the Inn

2.30: A New Way to Pay Old Debts

Week 3

Monday 25 June

10.30: The Unnatural Combat

2.30: The Roman Actor

7.00: The Great Duke of Florence

Tuesday 26 June

2.30: The Picture

7.00: The Maid of Honour

Wednesday 27 June

9.15: LECTURE: Believe As You List and the New World Order

10.30: Believe as You List

2.30: The Emperor of the East

Thursday 28 June

2.30: The City Madam

7.00: The Guardian

Friday 29 June

10.30: The Lovers’ Progress (revised)

2.30: The Bashful Lover