It’s always tempting to speculate on what might have happened if things had been different, and in the Artsnight programme Not Shakespeare, broadcast on 19 June Andrew Marr looked at the world of the Elizabethan and Jacobean theatre, and what we might now make of the playwrights of the time if Shakespeare had not existed.

Quoting the programme description “Andrew Marr…wants to champion some great Renaissance dramatists whose stories have been neglected because they worked at the same time as William Shakespeare. Andrew believes our obsession with the Bard of Avon has fatally distorted our view of the Tudor and Jacobean period.”

Those coming under discussion were John Webster, Christopher Marlowe, Ben Jonson and John Ford. It’s a good moment for this investigation as productions of their work are currently on stage, or in preparation. John Ford, in particular, has been the subject of The Ford Experiment at Shakespeare’s Globe. On 26 September a study day takes place where scholars and theatre practitioners share thoughts about Ford, culminating in The Lady’s Trial being performed at the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse by Edward’s Boys from King Edward’s School in Stratford-upon-Avon (also on 27 September).

Another play by John Ford, Love’s Sacrifice, has its last performances at the Swan Theatre in Stratford-upon-Avon this week, so you’ll have to hurry to catch it. Marr’s programme includes an interview with Catrin Stewart who plays Bianca in this production, talking about the strength of Ford’s heroines. His interest in women and psychology have often been compared with Shakespeare’s.

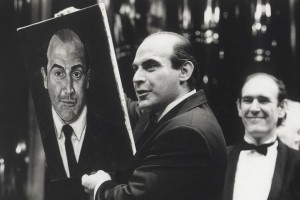

Marr also interviews Trevor Nunn, under whom the Swan Theatre opened in 1986 with the specific aim of investigating “Non-Shakespeare” plays. Nunn’s production of Ben Jonson’s Volpone is in preparation. Christopher Marlowe’s play The Jew of Malta is currently playing at the Swan Theatre, but Marr seems obsessed by Marlowe’s death, promoting the completely unsubstantiated idea that he might have faked his death and gone on to write plays under the pseudonym of Shakespeare. Thankfully Justin Audibert the director of the current production of The Jew Of Malta pointed out the enormous differences in style and substance between Marlowe and Shakespeare.

Eion Price has written a thoughful post on the programme on his Asidenotes blog. He notes that in spite of the aim, Marr’s programme did little to remove Shakespeare from the equation (though it did at least ask the question). Much of the discussion centred around the personalities of the different writers as seen in their work.: Marlowe the brilliant maverick, living fast and dying a violent death while still in his twenties, and Jonson the abrasive Londoner with a chip on his shoulder, always drawing attention tot his intellectual superiority. These comments shed light on Shakespeare’s own character: gentler, more countrified, less obsessed with the minutiae of everyday life, but commenting on big events in a subtle way. And, it has to be said, writing it in words that stick in the mind and speak to the heart.

Another “what if” question about the Elizabethan and Jacobean theatres has come under examination in Chris Laoutaris’s book Shakespeare and the Countess: the Battle that Gave Birth to the Globe. Laoutaris recently addressed the Hay Festival on the subject of the book, attracting new attention.

Elizabeth, Lady Hoby, nAe Elizabeth Cooke (1528-1609), Late 18th cent.. Artist: Bone, Henry (1755-1834)…DE718R Elizabeth, Lady Hoby, nAe Elizabeth Cooke (1528-1609), Late 18th cent.. Artist: Bone, Henry (1755-1834)

Laoutaris’s research over several years investigated the role played by the elderly, belligerent widow Lady Elizabeth Russell, who succeeded in preventing Shakespeare and his company from moving into the Blackfriars Theatre in 1596. She appears to have done so by sheer force of personality, intimidating many of the right people. The Lord Chamberlain’s men were left in the position of having no secure home for their company, hence their building in 1599 of the Globe Theatre. Intriguing questions are raised by the book: what would have happened if the company had moved into an indoor theatre so much earlier? How would it have affected Shakespeare’s writing, and that of other playwrights such as Jonson if the Globe had never existed? And how would it have affected the finances and status of Shakespeare and his fellows?

Russell was a Puritan, and although her main motive was NIMBYism, she would have been happy to see the players disappear completely. Their move across the river to the south bank, home of bear-baiting pits and brothels, enlarged this centre of entertainment. Most interestingly, the innovative way the Globe was funded made Shakespeare a wealthy man. To quote Laoutaris’s article, “To fund the enterprise the Burbage brothers hit on an entirely unprecedented business model. They offered a larger interest in the venture to Shakespeare and four other actor-sharers than had ever before been negotiated. Each paid £100 towards the cost of completing the playhouse. In exchange they became part-owners of the Globe, able to reap 10 per cent of the profits. Elizabeth Russell had unwittingly secured Shakespeare’s long-term success and his indelible association with the Globe.”

There’s a full discussion of the book in this review from last year, and this link is to an article on the book by Laoutaris himself in April 2015.