On 14 September Gregory Doran becomes Artistic Director of the Royal Shakespeare Company, the most high-profile job in the world of Shakespeare.

The RSC was founded in 1961 by the young Peter Hall, renaming and giving new life to the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre. Hall instituted three-year contracts for talented but unknown actors. Seasons without stars followed, and Hall insisted on giving the RSC a London home at the Aldwych Theatre where the Company produced a mix of modern and classic plays. The RSC began as the opposition to the West End under a revolutionary director, but inevitably has become the establishment. Up to now the Company has had only five Artistic Directors: Peter Hall, Trevor Nunn, Terry Hands (Nunn and Hands shared the role from 1978 to 1986, but each also held the job individually), Adrian Noble, Michael Boyd and now, number six, Gregory Doran.

The past ten years under Michael Boyd have been dominated by the transformation of the theatre spaces, by the need to reestablish the company ideal, and by two major and highly successful performance projects: the 2006-7 Complete Works Festival and the 2012 World Shakespeare Festival.

Gregory Doran first joined the RSC in 1987 as a member of the acting company, having trained at the Bristol Old Vic following his degree. He became an Assistant Director with the Company, and in 1992 directed his first solo production, Derek Walcott’s version of The Odyssey at The Other Place. Since then he’s worked consistently with the RSC but has also worked on many outside projects: he directed his partner Antony Sher in Titus Andronicus in South Africa, directed the York Mystery Plays, wrote The Shakespeare Almanac, worked on Michael Wood’s Searching for Shakespeare TV series, was on the Editorial Advisory Board for the RSC Shakespeare Complete Works, and edited the double CDs of recordings from the British Library’s performance collections Essential Shakespeare Live and Essential Shakespeare Encore. Most recently he worked on the British Museum’s current Shakespeare exhibition.

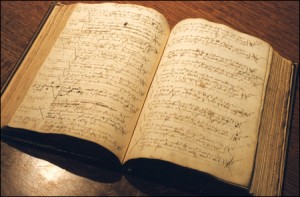

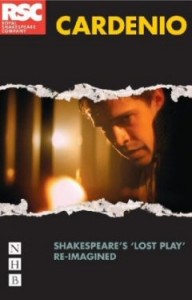

For the RSC he’s directed around half of Shakespeare’s plays and many by his contemporaries. He led the 2002 Jacobethan season and 2005 Gunpowder season, both in the Swan, and has specialised in plays with a historical focus: an adaptation of Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, Written on the Heart, and attempted a reconstruction of Shakespeare’s lost play Cardenio. Several of his productions have been filmed, Hamlet and Julius Caesar directed by himself. There’s a summary of his career here.

For the RSC he’s directed around half of Shakespeare’s plays and many by his contemporaries. He led the 2002 Jacobethan season and 2005 Gunpowder season, both in the Swan, and has specialised in plays with a historical focus: an adaptation of Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, Written on the Heart, and attempted a reconstruction of Shakespeare’s lost play Cardenio. Several of his productions have been filmed, Hamlet and Julius Caesar directed by himself. There’s a summary of his career here.

His work shows an eye for clever visual metaphor: there was a striking moment in the trial scene in The Merchant of Venice when Shylock’s money was thrown onto the stage, which Shylock then slipped and slithered on.

In his production of The Winter’s Tale the dock Hermione had been tried and condemned on reappeared as the podium on which she stood and came back to life in the statue scene. He gets terrific performances from his actors and has the ability to attract the best: Harriet Walter as Cleopatra, David Tennant as Hamlet, Judi Dench as the Countess of Rousillon, to name but three, and successfully directed Antony Sher in both Macbeth and The Winter’s Tale.

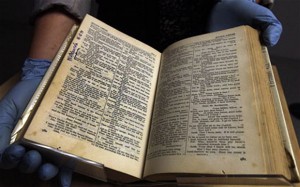

He has built up the respect of actors, directors and academics and the media, and done his fair share of broadcasting himself. These videos about Shakespeare’s First Folio were recorded for the RSC a few years ago, using the Royal Shakespeare Company’s own copy of the book.

He’s been called “one of the great Shakespearians of his generation”. So what might we expect of Gregory Doran as Artistic Director of the RSC?

After his predecessor has spent the last ten years necessarily concentrating on buildings and company, Doran has said he aims to bring the focus back to Shakespeare. I’m hoping he’ll continue to work on building a company while also encouraging great acting and training new directors, investigating how Shakespeare should be performed in the 21st century. I’ve heard that he want to re-establish a permanent London home for the RSC which would place the company back in the mainstream of theatrical innovation. And he’s sure to want to continue to collaborate with international partners.

Doran’s journey to the top has been an Odyssey in itself, taking even longer than Odysseus’s return from the Trojan War. It’s a homecoming, but also a new and exciting adventure.