The National Portrait Gallery in London’s new exhibition celebrates the careers of the earliest English professional actresses. Entitled The First Actresses: Nell Gwynn to Sarah Siddons it neatly documents womens’ increasing respectability in the world of the theatre.

In Shakespeare’s day women could not appear on stage publicly, and it was only with the accession of Charles II in 1660 that the position changed. Private theatricals were a different matter however, aristocratic ladies appearing in court masques from the early seventeenth century, and one of the paintings in the exhibition, dating from 1775, shows three such ladies in the roles of the three witches in Macbeth, though it doesn’t record an actual performance. There’s a full description of the painting on the website.

Sometimes Shakespeare deliberately seems to make his women masculine, as with Queen Margaret in the Henry VI plays, described as “she-wolf of France”, Tamora in Titus Andronicus who’s completely ruthless and Lady Macbeth who asks “unsex me here”. All three daughters in King Lear show their masculine side at different points in the play.

Of course there’s that plot device that’s almost a Shakespeare comedy trademark, a young girl disguising herself as a boy. This one occurs in Twelfth Night, The Two Gentlemen of Verona, Cymbeline and As You Like It, and there are also plenty of straight-talking women like Beatrice in Much Ado About Nothing and Katherina in The Taming of the Shrew. Often the dominant woman is balanced by the foil of a younger and more passive girl.

Shakespeare wrote for a known group of actors, and it’s noticeable in both A Midsummer Night’s Dream and As You Like It that he writes parts for two boys, one tall and fair, the other shorter and dark, both good comic actors. He’s able to use these differences to great effect in A Midsummer Night’s Dream where much of the comedy revolves around the statures of Helena, the “painted maypole” and Hermia “low and little”. There’s a minor textual problem with this in As You Like It. When Rosalind and Celia talk about running away Rosalind describes herself as “more than common tall”, yet Orlando has already been told that “the taller is his daughter [Celia]”. Some editors have assumed that this is an error, but Shakespeare could be building in a visual joke. Rosalind’s imagination begins to run away with her the moment the idea of escaping is suggested:

Were it not better,

Because that I am more than common tall,

That I did suit me all points like a man?

A gallant curtle-axe upon my thigh,

A boar-spear in my hand; and in my heart

Lie there what hidden woman’s fear there will,

We’ll have a swashing and a martial outside.

The actor playing Celia needs only to cast a meaningful look at the audience to make a joke of this lovely moment.

And then there are Juliet and Cleopatra, two heroines who really carry the play they appear in. Shakespeare must have known that he had talented boys who could be convincing in these roles. In both plays, the female lead is a much better role than the male. Reputations are rarely made by an actor playing Romeo orAntony, whereas Juliet and Cleopatra can be high points in an actress’s career, though admittedly this is partly because of the scarcity of strong roles for women.

It’s difficult for anyone, man or woman, to live up to Enobarbus’s description of Cleopatra:

For her own person,

It beggar’d all description: she did lie

In her pavilion – cloth of gold, of tissue-

O’er-picturing that Venus where we see

The fancy outwork nature.

And:

Age cannot wither her, nor custom stale

Her infinite variety: other women cloy

The appetites they feed, but she makes hungry

Where most she satisfies.

Shakespeare wrote some of the greatest theatrical roles for women ever created. The benefit of writing for boys may be that his heroines seem more modern than the heroines of some of the writers who came after him. This exhibition illustrates how Shakespeare helped them to reach the highest status among actors and artists.

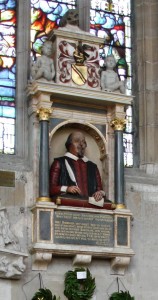

![william-shakespeare-portrait[1]](https://theshakespeareblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/11/william-shakespeare-portrait1-300x300.jpg)