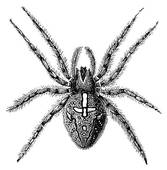

Autumn’s coming round, and that means we are all seeing more spiders in homes, gardens and in the countryside. Spiders have always got a bad press. In folklore they’re associated with evil, malevolence, and rumoured to be venomous.

Autumn’s coming round, and that means we are all seeing more spiders in homes, gardens and in the countryside. Spiders have always got a bad press. In folklore they’re associated with evil, malevolence, and rumoured to be venomous.

Spiders don’t do themselves any favours. Weaving webs which people walk into, or hiding in our houses where we spot them out of the corner of our eyes running across the floor or hanging from the ceiling, spiders are a nuisance. But looked at from another point of view spiders are our friends. Tiny money spiders are said to be lucky. Spiders catch flies which spread disease, they are industrious, and they construct the most beautiful webs.

Shakespeare’s aware of their positive qualities. In A Midsummer Night’s Dream one of the fairies is called Cobweb and Bottom comments on the fact that these webs can be used to bind wounds. “If I cut my finger, I shall make bold with you”.

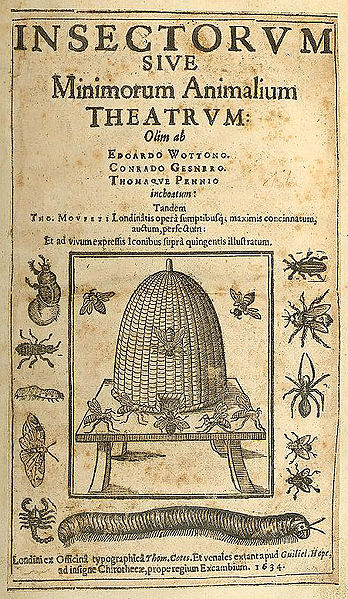

Thomas Muffet (or Moffet) was an Elizabethan physician fascinated by insects and spiders and their uses. He is reputed to be the father of “Little Miss Muffet” who is frightened by the spider in the nursery rhyme, though there’s no evidence. A copy of his posthumously published book Insectorum Sive Minimorum Animalium Theatrum is kept at the Shakespeare Centre Library and Archive. Spiders themselves could be used for treating illness: a live spider encased in butter or honey and swallowed was thought to be therapeutic (at this period the remedy was often almost more unpleasant than the disease).

Thomas Muffet (or Moffet) was an Elizabethan physician fascinated by insects and spiders and their uses. He is reputed to be the father of “Little Miss Muffet” who is frightened by the spider in the nursery rhyme, though there’s no evidence. A copy of his posthumously published book Insectorum Sive Minimorum Animalium Theatrum is kept at the Shakespeare Centre Library and Archive. Spiders themselves could be used for treating illness: a live spider encased in butter or honey and swallowed was thought to be therapeutic (at this period the remedy was often almost more unpleasant than the disease).

Most of Shakespeare’s references to spiders though fit the stereotype. Richard III is likened to many unpleasant animals, but the scuttling, malevolent spider is the most abiding. Richard sets a trap like a spider’s web into which his enemies fall one by one. One character warns another:

why strew’st thou sugar on that bottled spider

Whose deadly web ensnareth thee about?

When Antony Sher played the role in 1984 for the Royal Shakespeare Company he wore a tight-fitting black costume and wielded a pair of crutches to help him move across the stage at lightning speed. He was the malevolent spider personified.

Shakespeare also used the spider motif when writing about the Duke of York, Richard’s father, in Henry VI Part 2. He too is a plotter:

My brain, more busy than the labouring spider,

Weaves tedious snares to trap mine enemies

In Henry VIII two nobles jealously observe the ambitious but low-born Cardinal Wolsey who

spider-like

Out of his self-drawing web, ‘a gives us note

The force of his own merit makes his way.

One of my favourite speeches in Shakespeare involves a spider. In The Winter’s Tale Leontes uses what seems an unlikely image, of a spider concealed in a drink, to explain the agony of jealousy. For Leontes it’s the suspicion of his wife’s infidelity that causes pain, not the infidelity itself. Another jealous husband, Othello, expresses the same sentiment, and there too the audience knows the jealousy is unfounded.

In both cases the men are blind to all arguments, and the speech gives a glimpse into the frightening world of the obsessive. Shakespeare brilliantly chooses this image with its strong emotional associations of fear, suspicion and evil. The cause may be imaginary but the pain to the sufferer is no less real:

There may be in the cup

A spider steep’d, and one may drink; depart

And yet partake no venom (for his knowledge

Is not infected), but if one present

Th’abhorr’d ingredient to his eye, make known

How he hath drunk, he cracks his gorge, his sides

With violent hefts. I have drunk, and seen the spider.