The actor Peter O’Toole has recently announced his retirement from stage and screen, shortly before his 80th birthday. His reason? “The heart for it has gone out of me: it won’t come back.” It occurred to me that it’s unusual for actors to deliberately retire. Some, like Sir John Gielgud, never lose the appetite: he lived to be 96 and played cameo roles in no fewer than 4 films only 2 years before his death. Few follow the path set by William Charles Macready, the greatest actor of the mid nineteenth century, who left the stage in his fifties and spent the last 20 years of his life in happy retirement.

Peter O’Toole has always been an unusual actor. He went into acting almost by chance, and after drama school spent three years in rep at the Bristol Old Vic in around 70 different plays. By the time he came to the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre in 1960 he’d already won a best actor award, and had begun a film career. At the age of 27 he took three significant parts in Stratford: Shylock in The Merchant of Venice, Petruchio in The Taming of the Shrew and Thersites in Troilus and Cressida.

All three parts showcased O’Toole’s confidence and intensity. Most of the reviewers commented on his dignity as Shylock, and the Evening Standard reviewer commented that he was “a human being of stature driven to breaking point by the inhumanity of others”, leading to him being “possessed” in the trial scene.

The Taming of the Shrew enabled him to showcase a different range of talents, “the most aggressive, virile, dominating Petruchio in years” according to one reviewer, a “whirlwind of masculine ego”. At six foot three, with intense blue eyes and trademark charm, he played the part “without undue swagger and braggadocio but with an inspired touch of the fantastic”. His Kate was the spirited 52-year old Dame Peggy Ashcroft. According to the prompt book for the production, in their first scene together she kicked a stool from under him, threw it at him, slapped his face and bit his hand. His response was to kneel by her side to put her shoe back on for her. However it’s clear that by the end of the scene Petruchio was in control. Here’s a section of a commercial recording of The Taming of the Shrew featuring O’Toole and his then wife Sian Phillips from around 1962.

His performance of the bitter Thersites in Troilus and Cressida was less successful, though reviewers disagreed about how the part should be played. Some found him “all rage” while others commented that he was “subdued” and “underplayed the invective”. In all, though, it was a triumphant season.

One consequence of taking on the most promising young actors is always the risk that other people will also find them promising, and the planned London season was abandoned when he took the film role of Lawrence of Arabia. The film made him a screen legend.

He hadn’t finished with Shakespeare. In 1963 he played Hamlet, directed by Laurence Olivier, in the opening production of the newly-formed National Theatre, another opportunity to show his versatility. He and Orson Welles were interviewed by the BBC’s Monitor arts programme on the play.

He’s been nominated for 8 Oscars, but has never won one, though in 2003 he was awarded an honorary Oscar. His output has been prodigious, and varied. He gained a reputation for hell-raising with actors like Oliver Reed, Richard Harris and Richard Burton.

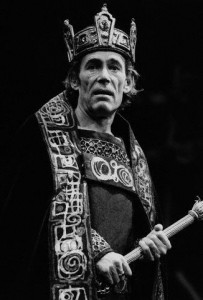

His career has always had its ups and downs. In 1980 he joined the Old Vic for another major Shakespeare play, Macbeth. The production was hotly anticipated, but universally derided. The Observer wrote “Chances are he likes the play, but O’Toole’s performance suggests that he is taking some kind of personal revenge on it.” I saw it on tour, finding on arrival at the theatre that our group were sitting in the front row of the stalls. It was a strangely old-fashioned production with some eccentric moments including the entrance of the ghost of Banquo in the banquet scene, literally dripping in stage blood. Although most of the costuming was “traditional” I have a pretty clear memory of O’Toole wearing a pink jogging suit for the action sequences.

His career has always had its ups and downs. In 1980 he joined the Old Vic for another major Shakespeare play, Macbeth. The production was hotly anticipated, but universally derided. The Observer wrote “Chances are he likes the play, but O’Toole’s performance suggests that he is taking some kind of personal revenge on it.” I saw it on tour, finding on arrival at the theatre that our group were sitting in the front row of the stalls. It was a strangely old-fashioned production with some eccentric moments including the entrance of the ghost of Banquo in the banquet scene, literally dripping in stage blood. Although most of the costuming was “traditional” I have a pretty clear memory of O’Toole wearing a pink jogging suit for the action sequences.

He’s recently mentioned his great love of Shakespeare’s sonnets, which he keeps with him constantly, and knows by heart. Here’s a link to a scene from his film Venus in which he delivers Sonnet 18. And in this radio interview he recites “My mistress’ eyes are nothing like the sun” impromptu: we can all forgive him forgetting the final couplet.

Nobody would wish Peter O’Toole the fate of Henry Irving, who died in the lobby of the Midland Hotel in Bradfordjust after coming off stage, or of Edmund Kean who collapsed on stage into the arms of his son Charles while they were appearing in Othello. After a career that has spanned over 55 years it’s to be hoped that he has years of contented retirement ahead of him.

15 December 2013: the death of Peter O’Toole has been announced today.