Watching part of the BBC’s current Tudor season I was enjoying the first part of Jonathan Foyle’s examination of Henry’s rule: Henry VIII: patron or plunderer when he got to the tapestries decorating Hampton Court Palace. The expert commented that there was a record that in 1529 Henry paid £1500 for a set of tapestries, a price comparable with that of a fully-rigged battleship. This staggering amount could be even higher if tapestries were made using silk and gold.

Watching part of the BBC’s current Tudor season I was enjoying the first part of Jonathan Foyle’s examination of Henry’s rule: Henry VIII: patron or plunderer when he got to the tapestries decorating Hampton Court Palace. The expert commented that there was a record that in 1529 Henry paid £1500 for a set of tapestries, a price comparable with that of a fully-rigged battleship. This staggering amount could be even higher if tapestries were made using silk and gold.

Tapestries are often found in stately homes and museums, but they don’t have the immediate impact of paintings, architecture or sculpture. Faded, often repaired, representing obscure mythological or biblical scenes, it’s difficult to appreciate how expensive they would have been to acquire, and what a status-symbol the best of them were. Mistress Quickly’s must have been fairly humble: Falstaff considers “the German hunting, in waterwork, is worth a thousand of these bed-hangers and these fly-bitten tapestries”.

More valuable tapestries than Mistress Quickly’s were those owned by the rich. In The Taming of the Shrew the old man Gremio bids for the hand of Bianca in marriage, boasting about the textiles that decorate his house:

My hangings all of Tyrian tapestry…

In cypress chests my arras counterpoints,

Costly apparel, tents, and canopies,

Fine linen, Turkey cushions boss’d with pearl,

Valance of Venice gold in needlework.

As the expert explained, the virtue of a set of tapestries to a royal court was their portability: a cold, damp and dark building could be quickly transformed by hanging up a set of tapestries. Tapestries had decorated buildings for several centuries before Shakespeare’s time. The famous Raphael Cartoons are one of the glories of the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. They were the original designs for a set of tapestries showing New Testament scenes commissioned by Pope Leo X for the Sistine Chapel. The cartoons were sent to Brussels where the tapestries were made, and many years later they were acquired by Charles 1. A few years ago several of the original tapestries were brought to London to be displayed alongside the cartoons for the first time since 1515: I couldn’t help feeling that the cartoons had aged much better than the tapestries for which they were created.

By Shakespeare’s day tapestries were being made in England. From about 1570 Ralph Sheldon, had set up a tapestry workshop in Barcheston, Warwickshire. His intention was to train and employ local people with the guidance of weavers from Flanders. The Sheldon tapestries were not as sophisticated as those created abroad, making them suitable for purchase by the middle classes, but they are certainly accomplished. The set of four county maps commissioned for Sheldon’s own house around 1590, were magnificent (the Warwickshire one is kept in Warwick).

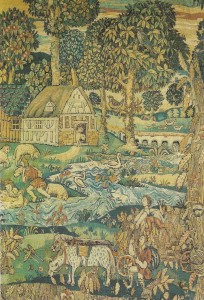

Sheldon tapestries can also be seen at Hatfield House, where tapestries of the Four Seasons now hang. They were originally created for Toddington Manor in Gloucestershire and acquired for Hatfield in 1846. The one illustrated is of summer, an English country scene showing fruit ripening on trees, wheat being harvested, and sheep being shorn in a lush landscape through which a generous river winds. A bed valance, shown at the top of the post, which has remained unfaded, shows a range of country activities and, like the Summer scene, could almost be an illustration of As You Like It.

Sheldon tapestries can also be seen at Hatfield House, where tapestries of the Four Seasons now hang. They were originally created for Toddington Manor in Gloucestershire and acquired for Hatfield in 1846. The one illustrated is of summer, an English country scene showing fruit ripening on trees, wheat being harvested, and sheep being shorn in a lush landscape through which a generous river winds. A bed valance, shown at the top of the post, which has remained unfaded, shows a range of country activities and, like the Summer scene, could almost be an illustration of As You Like It.

The Sheldon works had probably closed by about 1615, and in 1619 the tapestry works at Mortlake near London were founded. Within a few years they were making tapestries to rival the best being made in Europe, and they were patronised by both James 1 and Charles 1.

There are magnificent examples of Mortlake tapestries at Haddon Hall in Derbyshire, including a set depicting The Five Senses which were woven for Charles 1. The illustration is of a tapestry held by the Victoria and Albert Museum, illustrating the mythological story of Vulcan and Venus. It’s rather reminiscent of the decorations which Shakespeare, with his usual disregard for historical accuracy, imagines in Imogen’s bedchamber in Cymbeline. The chimney piece shows “chaste Dian bathing” and “golden cherubins” decorate the ceiling while the walls are:

hang’d

With tapestry of silk and silver, the story

Proud Cleopatra, when she met her Roman,

… a piece of work

So bravely done, so rich, that it did strive

In workmanship and value…

It’s a scene unlikely to have been seen in a pre-Christian British palace, and is thought to have been inspired by the writer Boccacio’s Decamaron. I’m certainly going to look at those rather faded tapestries with a different eye from now on, and should you want to watch these programmes, if you’re quick they are still available to watch again. The tapestry section is about 22 minutes into the first programme.

This is going to be a long comment Sylvia – I hope you don’t mind!

Living less than a mile from Barcheston (as the crow flies), I’ve always been astonished that items as beautiful and sophisticated as the Sheldon tapestries could have been produced in such a tiny place – it consists of only a handful of buildings including the manor house and church. It was Ralph Sheldon’s father William who initiated the tapestry workshop at Barcheston which was then continued by Ralph. William had bought the manor of Barcheston in 1561 and his will of 1570 refers to his having placed a man called Richard Hyckes (possibly a Flemish weaver) in the manor rent-free “in respect of the maintenance of making of tapestrye, arras, moccadoes, carolles, plometts, grograynes, sayes and sarges”. (I had to quote this because the words are so fantastic! – the latter six are apparently a range of coarse to fine fabrics). Richard had been appointed the Queen’s arrasmaker, head of the tapestry repair department of the Great Wardrobe in 1569.

The house in which the county maps were hung was Weston Park built in 1588 by Ralph Sheldon about 5 miles from Barcheston. Sadly it was demolished in the early 19th century – there is an engraving of it here – http://freepages.history.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~simba/cherington/imlh-westonpark1716.htm

Richard Hyckes lived to the amazing age of 97, outliving both William and Ralph and was buried at Barcheston. There is much more information at this website – http://www.tapestriescalledsheldon.info/p34_learn_index_pdfs.htm – although Hilary Turner, the researcher who put this together, questions whether calling all the tapestries “Sheldon” is accurate.

The Sheldons were wealthy and influential and intertwined by marriage with other important Midlands families – William Sheldon’s wife was the granddaughter of a Throckmorton, his son Ralph married a Throckmorton, and his sister-in-law was the grandmother of Robert Catesby (of the Gunpowder plot). William Sheldon also had connections with Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester.

It is interesting to speculate whether Shakespeare knew the Sheldons – he certainly knew Barcheston – he makes Justice Silence refer to “goodman Puff of Barson” in Henry IV Part 2, Barson being the 16th century spelling of Barcheston (it’s on the tomb of William Sheldon’s father-in-law in the church).

A nice connection of the Sheldons to Shakespeare is a copy of the First Folio which has been in the Folger Shakespeare Library (Folger 10) since 1922. It was purchased new in 1623 by Ralph’s son, another William, and remained in the family until sold in 1781. Sidney Lee said it was the only copy of the First Folio of which he could tell the full story of its ownership. It has the arms of Ralph’s grandson (another Ralph!) on its cover – http://luna.folger.edu/luna/servlet/detail/BINDINGS~1~1~6862~101847:Front-cover,-STC-22273-fo-1-no-10-