This summer Tate Britain is mounting an exhibition entitled Fighting History, on the subject of history painting, a rather unfashionable and neglected genre. From Ancient Rome to recent political upheavals, Fighting History looks at how artists have transformed significant events into paintings and artworks that encourage us to reflect on our own place in history.

From the epic 18th century history paintings…to contemporary pieces … the exhibition explores how artists have reacted to key historic events, and how they capture and interpret the past. Often vast in scale, history paintings engage with important narratives from the past, from scripture and from current affairs. Some scenes protest against state oppression, while others move the viewer with heroic acts, tragic deaths and the plights of individuals swept up in events beyond their control.

History painting had been regarded as the most prestigious branch of painting for hundreds of years before it became really popular in England in the late eighteenth century. The interpretation of real events like Benjamin West’s The Death of General Wolfe were perhaps the most important, but painters also depicted events from the more distant past, or imaginary events. The Victorian painter William Frederick Yeames painted the famous painting set during the English Civil War And When Did You Last See your Father? as well as The Death of Amy Robsart, that questions the mysterious death of Robert Dudley’s wife during Queen Elizabeth’s reign.

Inevitably, given the need for dramatic subjects, Shakespeare’s plays have often been the inspiration for English history painters. The Boydell Shakespeare Gallery was the largest and most ambitious project in which one hundred and sixty-seven paintings were created by thirty-three artists between 1791 and 1805, from which prints and an edition of Shakespeare’s works were also made for sale. In the introduction to Pape and Burwick’s book The Boydell Shakespeare Gallery, Burwick calls theatre painting “a genre in the process of defining itself”. Artists were allowed the freedom to decide what aspect of the play they wanted to focus on. Some of the paintings depict moments only described, or that must have happened, such as Northcote’s paintings of the killing of the little princes in the tower in Richard III. Burwick notes that Henry Fuseli “was undoubtedly the most bold in his experimentation, frequently choosing to represent the mental psychodrama rather than anything that might possibly be realized on stage”. Rather than looking for off-stage moments, as Northcote had done, Fuseli “sought out scenes which would allow him visually to externalize subjective experience”.

Fuseli’s painting of Henry V, Royal Shakespeare Company Collection; Supplied by The Public Catalogue Foundation

For instance in Henry V, Fuseli chose to depict the revelation of the conspiracy of Henry’s friends at Southampton: “Hal’s growth as wise and capable monarch comes into its final maturation in this scene”, and Fuseli captures the essence of the scene and of the play with its emphasis on the monarchy’s role in the nation. The Chorus reminds us why it is significant:

O England! model to thy inward greatness,

Like little body with a mighty heart,

What mightst thou do , that honour would thee do,

Were all thy children kind and natural!

Fighting History has received a number of unfavourable reviews from the newspapers, including The Guardian and the Telegraph. Spear’s found it “disappointing and baffling”, at least partly because the exhibition refuses to define what it means by history painting. The Arts Desk impatiently tells us: “it is surely quite easy to define. Didactic and preoccupied with grand narrative, showcasing the accomplishment and learning of the artist, it expounds themes from classical history or the Bible or immortalises pivotal, historically significant moments from the more recent past”.

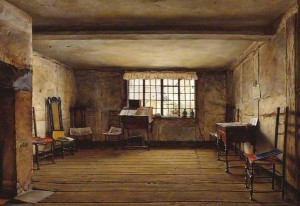

There’s not much room here for Fuseli’s psychological paintings of Shakespeare. I haven’t been to the exhibition but from the descriptions, theatre paintings seem to be have been excluded. Strangely, though, the exhibition does include one painting that has Shakespeare relevance. It’s Henry Wallis’s The Room in Which Shakespeare was Born, from 1853, that I happened to write about in May. The Arts Desk complains that with no “grand narrative” this is “miscast as history painting”. The FT disagrees, enjoying the way that history paintings can be “coded political comment”, (just as plays, especially Shakespeare’s plays, are and were), and congratulating the exhibition’s curators for including “peaceful scenes such as Henry Wallis’s serene [painting of the birthroom]” rather than solely the “pivotal, historically significant moments”.

For Culture 24 the aim of the exhibition is to “celebrate the emotional power of history painting and show its persistent place in art”. You’ve got until 13 September 2015 to see for yourself if it has succeeded.