You don’t have to look very far into Shakespeare’s works to find archaic words, or words difficult for us to understand. As well as coining new words, he made use of many that were probably already old-fashioned.

Many words have also changed their meanings, or have different associations. In 1947 Eric Partridge wrote his book Shakespeare’s Bawdy, drawing attention to many of the forgotten sexual references in the plays, and there have been many other books since: Frankie Rubinstein wrote a whole dictionary of Shakespeare’s sexual puns and their significance that included many hundreds of words. Nowadays we enjoy the fact that sexual innuendo is so widely used by the man held up for centuries as the height of respectability.

Bowdler’s expurgated Family Shakspeare was first published, in 1807,”those words and expressions omitted that cannot with propriety be read aloud in a family”, and removing “any indelicacy of expression”. It was so popular that by 1827 it had gone through five editions. Bowdler probably didn’t spot some of the bawdy puns listed by Partridge and Rubinstein, and he would have been wise to avoid cleaning up Shakespeare’s Venus and Adonis. This delightful passage, in which Venus tries to seduce Adonis, must have raised many a blush in polite circles over the years.

I’ll be a park, and thou shalt be my deer;

Feed where thou wilt, on mountain or in dale:

Graze on my lips; and if those hills be dry,

Stray lower, where the pleasant fountains lie.

Within this limit is relief enough,

Sweet bottom-grass and high delightful plain,

Round rising hillocks, brakes obscure and rough,

To shelter thee from tempest and from rain

Then be my deer, since I am such a park.

Discussions of sexual innuendo always bring to mind the Nudge, Nudge sketch from Monty Python where Eric Idle quizzes Terry Jones: “Is your wife a sport? Is she interested in photographs”. Of course, it’s all in the delivery, and the same is true in Shakespeare. It’s become quite common for Hamlet to heavily stress the first syllable of “country” when he asks Ophelia “Do you think I meant country matters?” as if to demonstrate to an ignorant audience that Shakespeare could be a bit smutty. “Nudge, nudge, wink, wink, say no more” as Eric Idle said so many times.

At the Heritage Open Day display by the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust last weekend one of the items on display was a beautifully-carved wooden knife sheath dating from 1602, probably worn by a woman, and possibly a wedding-gift. The caption referred to the fact that the word “knife” had a sexual meaning, and quoted from Romeo and Juliet, where Paris is one “that would fain lie knife aboard”.

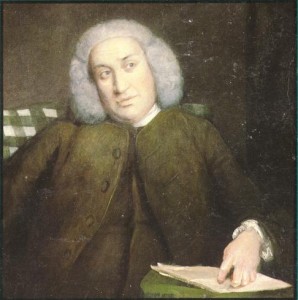

The issue of words and their associations made me think of Samuel Johnson’s essay on Macbeth for The Rambler, published in October 1751. In Walter Raleigh’s 1916 collection Johnson on Shakespeare this essay is described as “Poetry debased by mean expressions. An example from Shakespeare”. Johnson’s argument is that language needs to be appropriate for the sentiment expressed. Truth “loses much of her power over the soul, when she appears disgraced by a dress uncouth or ill-adjusted”. Johnson takes issue with the passage where Lady Macbeth calls on spirits to strengthen her resolve:

Come, thick night,

And pall thee in the dunnest smoke of hell,

That my keen knife see not the wound it makes,

Nor heaven peep through the blanket of the dark,

To cry ‘Hold, hold!

Johnson asserts ” In this passage is exerted all the force of poetry, that force which calls new powers into being, which embodies sentiment, and animates matter”, but his next statement is more difficult for us in the twenty-first century to understand: “Yet, perhaps, scarce any man now peruses it without some disturbance of his attention from the counteraction of the words to the ideas”.

There are several words in this short passage that Johnson finds offensive: The invocation of night, and the smoke of hell, is ruined by the use of the word “dun”, “an epithet now seldom heard but in the stable”. Then, “knife”. “This sentiment is weakened by the name of an instrument used by butchers and cooks in the meanest employments: we do not immediately conceive that any crime of importance is to be committed with a knife; or who does not, at last, from the long habit of connecting a knife with sordid offices, feel aversion rather than terror?” Finally, “this is so debased by two unfortunate words, that… I can scarcely check my risibility;…for who, without some relaxation of his gravity, can hear of the avengers of guilt peeping through a blanket? It’s an interesting insight into eighteenth-century sensibilities.

The charge of unsuitable language could not apply to the most famous speech in the play: Is this a dagger which I see before me,

The handle toward my hand? Come, let me clutch thee.

I have thee not, and yet I see thee still.

Art thou not, fatal vision, sensible

To feeling as to sight? or art thou but

A dagger of the mind, a false creation,

Proceeding from the heat-oppressed brain?

I see thee yet, in form as palpable

As this which now I draw.

Thou marshall’st me the way that I was going;

And such an instrument I was to use.

Mine eyes are made the fools o’ the other senses,

Or else worth all the rest: I see thee still,

And on thy blade and dudgeon gouts of blood,

Which was not so before.

Fifteen lines in which Macbeth describes his vision without once using the word “knife”. Samuel Johnson must have approved. The exhibition Shakespeare in the Eighteenth Century is on at Dr Johnson’s London house until 28 November, complemented by lots of events.