Queen Elizabeth II leaving Shakespeare’s Birthplace on her first visit to Stratford as reigning monarch, 1957.

On 9 September 2015 Queen Elizabeth II becomes officially the longest-reigning British monarch in history, having survived for over 63 years, just longer than Queen Victoria. The Queen has refused to mark the day in any way, but the press are going to town printing supplements and selling commemorative knick-knacks. In what has been dubbed “the most patriotic village in England”, Ilmington, just a few miles from Stratford, a Glyndebourne-style concert Long to Reign Over Us will be staged on Saturday evening.

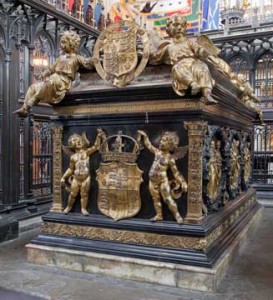

The Queen has had a long association with Stratford and Shakespeare, first visiting the town as reigning monarch in 1957, then opening the Swan Theatre in 1986 and reopening the RST after its extensive transformation in March 2011. It is the Royal Shakespeare Company after all! In between she opened the elegant Swan water Fountain on the Bancroft in 1996 to celebrate the 800th anniversary of the town of Stratford-upon-Avon being granted borough status in 1196.

Our present monarch can’t be said to be a great theatre-lover, or Shakespeare-lover, while Prince Charles is President of the RSC and a frequent attender of performances in the Stratford theatres.

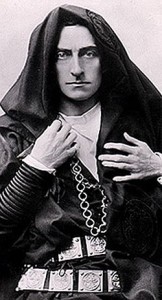

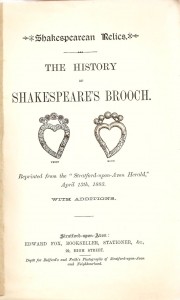

Queen Elizabeth II and Queen Victoria have between them clocked up 125 years on the throne. Victoria was a more regular theatregoer, and in her biography Helen Rappaport notes that she liked both Charles Macready and Charles Kean. She noted that she enjoyed Shakespeare’s King John and Richard III, but she really preferred the less weighty melodrama and light comedies. The Merry Wives of Windsor was too coarse for her, and it seems probable that it was really Prince Albert who was the Shakespeare fan. He was a member of the Committee formed to buy Shakespeare’s Birthplace in 1847. During the 1840s they visited the Theatre Royal Haymarket and Kean gave a number of command performances at Windsor, including The Merchant of Venice, Hamlet and Macbeth.

In 1848, a year of revolutions in many European countries, Victoria and Albert were criticised among other things for preferring foreign plays to those written by English authors. Their response was a number of high profile visits to London theatres in an attempt to show solidarity with their subjects. In the 1850s they often visited Charles Kean’s Princess’s Theatre where he staged spectacular revivals of Shakespeare. Their approval helped to make theatregoing respectable.

Before Victoria’s day King George IV associated himself with Stratford and Shakespeare, pledging money in the early 1820s to the building of a mausoleum to Shakespeare (an project that failed), then in 1830 granting the Shakspearean Club the right to call itself The Royal Shakspearean Club, a title they continued to use for some years.

Shakespeare himself wrote many of his plays knowing they would be performed before the monarch. In Shakespeare’s First Folio Ben Jonson commented that both Queen Elizabeth 1 and King James enjoyed his plays.

Sweet swan of Avon! what a sight it were

To see thee in our waters yet appeare,

And make those flights upon the bankes of Thames,

That so did take Eliza, and our James!

When James became King of England in 1603 one of his first actions was to adopt Shakespeare’s company as the King’s Men, and in A Midsummer Night’s Dream Shakespeare had already written an oblique compliment to Queen Elizabeth 1:

That very time I saw …

Cupid all arm’d: a certain aim he took

At a fair vestal throned by the west,

And loos’d his love-shaft smartly from his bow

As it should pierce a hundred-thousand hearts: B

ut I might see young Cupid’s fiery shaft

Quench’d in the chaste beams of the watery moon,

And the imperial votaress passed on,

In maiden meditation fancy free.

Shakespeare was said to have written The Merry Wives of Windsor in direct response to a request from the Queen to see Falstaff in love.

Time and again Shakespeare wrote about the failings of successive monarchs from the vanity of Richard II and the ineffectiveness of Henry VI to the evil of the king who butchered his nobles and even members of his own family, Richard III. Many of his Kings were tormented: Henry IV guiltily worried that he deposed his predecessor, and found himself in a similar situation “Uneasy lies the head that wears the crown”.

Our Queen might feel, like Shakespeare’s Henry V:

What infinite heart’s-ease

Must kings neglect, that private men enjoy!

And what have kings, that privates have not too,

Save ceremony, save general ceremony?

Nobody would suggest that hers has been an easy job. For over sixty-three years she’s welcomed heads of state, held meetings with twelve different prime ministers, and carried out endless public duties, always smiling and waving, never able to say what she really thinks. In all that time this remarkable woman has hardly put a foot wrong. She is now said to be the most famous woman on the planet, and the stability of this country is symbolised by the continuity of her reign. Nobody alive today “will look upon her like again”.