There’s lots going on just now with all-female and cross-gender productions of Shakespeare, so this post is a quick round-up. Following their success with an all-female Julius Caesar directed by Phyllida Lloyd, the Donmar Warehouse recently announced they will be staging another all-female Shakespeare this autumn, with Henry IV. Harriet Walter will take the role of the King. The artistic director of the Donmar, Josie Rourke, says the all-female Julius Caesar had sparked an important debate to “open up our national playwright to those who have been denied him through gender, heritage or class”. “There is a mission behind this work, which is the question: who owns Shakespeare? Yes, it’s about gender; it’s also about diversity, it’s about class and it is about how we can extend the project of these productions beyond our stage and into the lives of , particularly, young people.” Full details are on the Donmar website.

Over in New York Manhattan’s All-Female Shakespeare Company is presenting Romeo and Juliet for 2014 in their Free Shakespeare in the Parks season. “Manhattan Shakespeare Project provides an opportunity for female actors to play traditionally male roles as well as an opportunity to break into the male dominated theater industry in directing, producing, writing, and stage production.” ” This version of Romeo and Juliet is an ensemble of six women who through physicality, movement, imagination and the bard’s own words literally put the audience in the middle of a tour of Verona as the events unfold in a reverse theatre in the round.” The play is directed by Reesa Graham. Full details are on the website but the production will be staged throughout June in several different locations, all free.

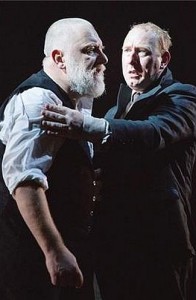

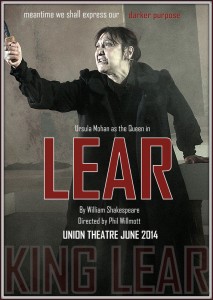

Just opening at The Union Theatre, Union St London is a new production of King Lear with a female lead. This production “puts a mother at the heart of the action supposing that it is a queen who, weary of public office, divides the kingdom amongst her daughters. But the old woman finds it impossible to retire gracefully and as her mental faculties begin to fail she’s cast out by her eldest children”. This production by Phil Wilmott runs until 28 June.

Just opening at The Union Theatre, Union St London is a new production of King Lear with a female lead. This production “puts a mother at the heart of the action supposing that it is a queen who, weary of public office, divides the kingdom amongst her daughters. But the old woman finds it impossible to retire gracefully and as her mental faculties begin to fail she’s cast out by her eldest children”. This production by Phil Wilmott runs until 28 June.

For anyone interested in female Hamlets there’s a new project called Hamlet The Series which breaks the play down into six sections all available on YouTube. The video is the first of the six: links are on the YouTube page. It’s a modern dress version with several roles played against gender. This explanation appeared on the Kickstarter campaign page: ” There are multiple reasons to have a female Hamlet. One is the fresh look it gives to the play’s exploration of gender proclivities, love, and sex. Another, related, is the new light it throws on the many professions of love for the Prince, and their questionable sincerity… But the biggest is that Hamlet is a character who, more than any other, refuses to be kept in any one category… A female Hamlet will not be exactly like a male Hamlet, but will remain fundamentally Hamlet, and help us to see what those fundamentals are”.

It was filmed at the Evanston Community Media Center near Chicago and makes use of the multimedia equipment available. I liked the idea of Hamlet delivering her soliloquies to her tablet computer. Sometimes we see her speaking to the computer, and other times we see what’s being filmed, begging the question who is she speaking to? Who is the audience?