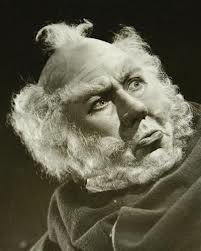

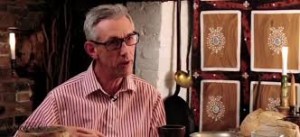

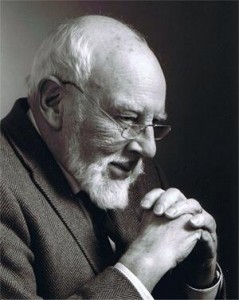

I’ve just heard the sad news that veteran Royal Shakespeare Company actor Jeffery Dench has died. He will be remembered fondly, and greatly missed, by thousands who saw him play a mind-boggling range of roles on the RSC’s stages.

I’ve just heard the sad news that veteran Royal Shakespeare Company actor Jeffery Dench has died. He will be remembered fondly, and greatly missed, by thousands who saw him play a mind-boggling range of roles on the RSC’s stages.

His career with the RSC began in the 1960s when he was in the company’s landmark Wars of the Roses, followed by the David Warner Hamlet. He quickly established himself in comedy roles such as Sir Andrew Aguecheek in Twelfth Night and Master Page in The Merry Wives of Windsor.

He had a particular talent for playing old men: one of the first things I saw him play was Adam in As You Like It in 1977/8, opening the play by getting in some wrestling practice with his Orlando (Peter McEnery/James Laurenson), despite his apparent age. Again in Merry Wives, he played Justice Shallow in both 1992 and, his last performance, in 2006. Both these have Shakespearean resonance: the faithful old servant Adam is supposed to have been a role written by Shakespeare for himself, and Shallow is involved in the discussions that might relate to the Lucy family of Charlecote. In one of the Histories, he also played a character called Thomas Lucy.

There was plenty of non-Shakespeare too: the Troll King to Derek Jacobi’s Peer Gynt in 1982, and the Water Rat in at least one of the revivals of Toad of Toad Hall.

It wasn’t all comedy: in 1974/5 he played Gloucester in Buzz Goodbody’s adaptation of King Lear, and as well as Pistol in Henry V he played a multitude of lords and soldiers in Terry Hands’ magnificent cycle of all three parts of Henry VI in 1977/8.

I came to live in Stratford in 1979 and saw all the plays repeatedly. He seemed to be in everything. As well as Brabantio in Othello and Cinna the conspirator in Julius Caesar he played Cymbeline in the play of the same name, his sister Judi playing his daughter Imogen. His most enjoyable performance of the year for me, though, was the doubling of Antiochus and the Pander in Pericles at The Other Place. In charge of the brothel where the innocent heroine Marina is held he was both frighteningly grotesque and blackly comic.

As part of the 1979 Stratford company he automatically became part of the company for what for me has been the RSC’s outstanding achievement, The Life and Adventures of Nicholas Nickleby, staged initially at the Aldwych in 1980-81, subsequently in New York, and filmed for Channel 4. Like almost everyone in the case he played many characters, though again most memorably the repellent old suitor Arthur Gride.

When not playing grotesque old men, he brought humour, warmth and integrity to his parts. As a member of the audience, seeing Jeffery Dench’s name on the cast list was a guarantee of quality. Shakespeare did write brilliant leading roles for Burbage and others, but he also wrote for a known company of talented professionals. The RSC has been fortunate to have among its regulars a number of high-quality actors, safe hands that could carry the plays along with distinction. Jeffery Dench was one of those, and if there were to be a late twentieth-century version of the page in the First Folio “The Names of the Principal Actors in all These Plays”, his name would be on the list.

Full details of his RSC career can be found by searching by name on the RSC Performance Database