On Saturday morning Stratford-upon-Avon’s Music Festival began with a Festival Fanfare entitled Lend Me Your Ears, played by the brass ensemble from King Edward VI School. Performed on the steps of the Royal Shakespeare Theatre it was a reminder of the importance of music to Shakespeare and of live music to the theatre.

Rather than sticking to obvious music halls the Festival will include one free concert in a pub and another in one of the town’s hotels. And there will be performances in venues with Shakespearean connections including Holy Trinity Church, the Shakespeare Institute, the Town Hall and The Guild Chapel.

I particularly like the sound of the concert on Wednesday entitled “The Queene’s Speech”, by Charivari Agreable, which covers events leading up to Queen Elizabeth’s Tilbury Speech, the one that goes “I know I have the body but of a weak and feeble woman…” . It will include readings of Queen Elizabeth’s letters, sonnets by Shakespeare, with songs and instrumental dances from the period by Byrd and Dowland among others. This takes place in one of the most atmospheric buildings in the town, the Guild Chapel.

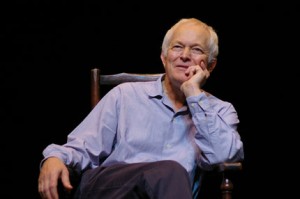

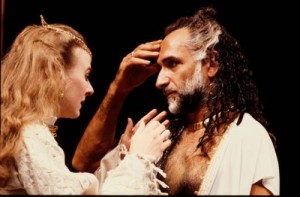

On 6 October RSC Artistic Director Greg Doran was interviewed for the Radio 3 programme Private Passions, in which he chose some of his favourite music. His love of music is apparent from his productions of Shakespeare, and not surprisingly he selected several Shakespeare-related pieces of music, including part of Duke Ellington’s music originally composed for a production of Timon of Athens at Stratford, Ontario which he used for his own production of the play.

As you might expect for a person whose life revolves around the spoken word, especially poetry, most of his choices were of songs. Paul Englishby’s setting of Sigh no more ladies from Much Ado About Nothing was one choice, and other examples included a recording of Kathleen Ferrier singing Blow the Wind Southerly, a Japanese folk song, a Bach Cantata sung by Janet Baker and a traditional South African wedding song.

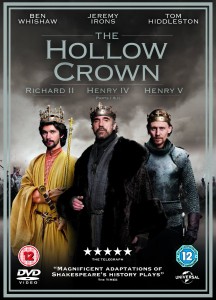

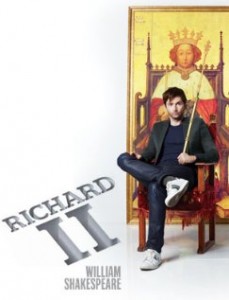

Evidence is now emerging that suggests the brain responds to poetry in very much the same way as it responds to music. New brain imaging techniques show that areas of the brain that deal with emotion and memory are more active when listening to poetry than prose. So Shakespeare may have been right when he wrote John of Gaunt’s lines in Richard II, spoken just before his death:

The setting sun, and music at the close,

As the last taste of sweets, is sweetest last,

Writ in remembrance more than things long past.

Professor Adam Zeman, quoted in the Daily Telegraph on 11 October explains “we are now seeing a growing body of evidence about how the brain responds to the experience of art”, “work that is helping us to make psychological, biological, anatomical sense of art”.

It was noted during the programme that most of Doran’s choices were of rather sad music, and typically he quoted Jessica’s comment in The Merchant of Venice “I am never merry when I hear sweet music”. Shakespeare also made the connection between music, poetry, personality and the importance of art, with Lorenzo’s speech:

The man that hath no music in himself,

Nor is not moved with concord of sweet sounds,

Is fit for treasons, stratagems and spoils;

The motions of his spirit are dull as night

And his affections dark as Erebus:

Let no such man be trusted.

The Stratford-upon-Avon Music Festival runs until 20 October and some of Paul Englishby’s music can be heard during the current production of Richard II at the Royal Shakespeare Theatre. Greg Doran’s Private Passions are available to listen again on BBC IPlayer.