This weekend is the most important of the year for Stratford-upon-Avon. Shakespeare’s life and works are celebrated with a whole range of events, but the most important is the parade which this year takes place on Saturday morning, 20 April, and will bring the centre of town to a standstill. I’ve taken part in it many times, usually accompanying guests from other countries or cultural organisations. It’s great fun because as you walk through the streets down to Holy Trinity Church you get the opportunity to introduce people who may not know much about the town to the story of Shakespeare in Stratford.

This weekend is the most important of the year for Stratford-upon-Avon. Shakespeare’s life and works are celebrated with a whole range of events, but the most important is the parade which this year takes place on Saturday morning, 20 April, and will bring the centre of town to a standstill. I’ve taken part in it many times, usually accompanying guests from other countries or cultural organisations. It’s great fun because as you walk through the streets down to Holy Trinity Church you get the opportunity to introduce people who may not know much about the town to the story of Shakespeare in Stratford.

Over the last couple of years I’ve taken a more practical role, and have become aware of the amount of organisation this event requires from the people of the town whether they are first-aiders, police specials, staff and boys at King Edward’s School, members of the bands, or the people who receive and arrange the flowers in Holy Trinity Church.

Over the last couple of years I’ve taken a more practical role, and have become aware of the amount of organisation this event requires from the people of the town whether they are first-aiders, police specials, staff and boys at King Edward’s School, members of the bands, or the people who receive and arrange the flowers in Holy Trinity Church.

Flowers play an important part in this ceremony. Shakespeare loved them, especially spring flowers. In this recent piece Germaine Greer comments on Shakespeare’s love of the spring. One of my favourite quotations from Shakespeare about flowers is also quoted by Greer:

daffodils,

That come before the swallow dares, and take

The winds of March with beauty; violets, dim,

But sweeter than the lids of Juno’s eyes

Or Cytherea’s breath; pale primroses,

That die unmarried, ere they can behold

Bright Phoebus in his strength

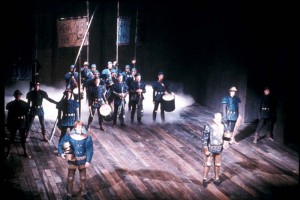

Perdita, who speaks these lines in The Winter’s Tale, is commenting regretfully that none of the most lovely flowers of the spring are blooming in the height of summer. Shakespeare is almost always an accurate observer of nature, but the winter now just passing has been so severe that the daffodils failed to come out in March, and are only now in full bloom. And the swallows have dared to come at the same time: we saw our first in Stratford just last Sunday, the 14th April. Migrating all the way from Africa each year they always really signal the arrival of spring.

For a young girl talking to her lover, Perdita has some surprising thoughts about the inevitability of winter and death. Daffodils come earlier than other signs of spring, and primroses shrivel before the sun warms the land. Florizel is to be strewn with flowers, but “not like a corpse; or if -not to be buried, but quick, and in mine arms”. The Winter’s Tale repeatedly concerns itself with death, rebirth, and the cycles of nature. Shakespeare, famously, is thought to have died on his birthday so it’s even more appropriate that the parade that marks his birthday ends with the decoration of his grave with the flowers of spring, celebrating his achievements and undying influence.

For a young girl talking to her lover, Perdita has some surprising thoughts about the inevitability of winter and death. Daffodils come earlier than other signs of spring, and primroses shrivel before the sun warms the land. Florizel is to be strewn with flowers, but “not like a corpse; or if -not to be buried, but quick, and in mine arms”. The Winter’s Tale repeatedly concerns itself with death, rebirth, and the cycles of nature. Shakespeare, famously, is thought to have died on his birthday so it’s even more appropriate that the parade that marks his birthday ends with the decoration of his grave with the flowers of spring, celebrating his achievements and undying influence.

The Birthday celebrations are an opportunity for people from around the world to pay their respects to Shakespeare, and there has been an international element to them for many decades. This year Bangladesh, New Zealand, Kenya and Brazil will be among the countries represented, along with people from many local schools, colleges and organisations. One of the joyful things about the parade is that the crowds who watch the procession can also join in.

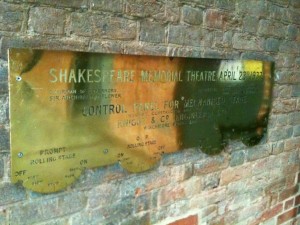

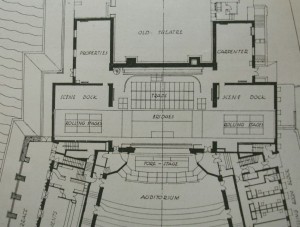

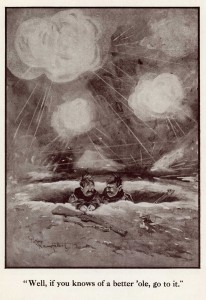

The USA is the country which above all has helped the development of Stratford, contributing to the building of the theatre, and providing the most constant of visitors to the town. The RSC’s productions of Julius Caesar and the musical Matilda have just opened in New York. Among the groups informally joining the procession will be a group from Boston, the city where on Monday, the city’s own most special day turned from jubilation to tragedy in the blink of an eye. At the end of The Winter’s Tale, wounds are healed but among the rejoicing there is a moment of “joy waded in tears” to remember the dead. While Stratford enjoys its own big day, those taking part will also acknowledge those places in the world suffering grief and devastation.