Last week I wrote about the three costumes for Prospero in The Tempest which form part of the RSC’s exhibition of historic costumes, Into the Wild. Just opposite them stand three quite different costumes, for the character Leontes in The Winter’s Tale.

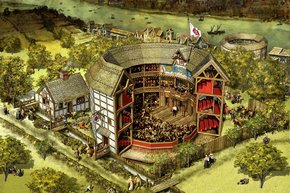

It’s a play that offers many opportunities for a costume designer. Unlike The Tempest, set on a mythical island, The Winter’s Tale has two completely different locations. The play begins in Sicilia, where Leontes rules, and ends there sixteen years later. The formality of his court is always a contrast with the Bohemian scenes of bumptious country life that make up the central scenes.

But the challenge for the costume designer isn’t just in differentiating between two very different locations. Leontes’ all-consuming jealousy and his belief in his wife’s adultery begins so suddenly and continues so unshakeably that it can be difficult for an audience to take seriously. Later on the play includes improbable coincidences and, apparently, a miracle. Costumes can help to locate Leontes’ court in time and place and to signal the progression of his state of mind on which much of the play depends. “Your actions are my dreams” he says to his accused wife.

The three costumes on display are for the 1986 Terry Hands production with Jeremy Irons, costumes designed by Alexander Reid, the 1999 production directed by Greg Doran with Tony Sher, designed by Robert Jones, and David Farr’s 2009 production designed by Jon Bausor, with Greg Hicks in the lead. The last two are directly comparable, being the costumes, or part of them, worn by Leontes for the scene in which his wife, Hermione, is tried for adultery. This great central scene includes the trial itself, the reading of the oracle, Leontes’ refusal to accept it, the offstage deaths of Hermione and their son Mamillius, and Leontes’ repentance. Beginning with the formality of the courtroom it ends with the disintegration of Leontes’ world.

For this scene Tony Sher’s costume consisted of a military uniform, highly decorated with medals, on top of which he wore a sumptuous fur cloak and crown. The costume suggested a nineteenth-century, perhaps Eastern European setting, literally a buttoned-up society. His earlier costumes had suggested he was losing control, but this one showed his determination to retain fully in power.

In the same scene Greg Hicks’ spare, troubled Leontes, wore a simple dark overcoat, the only decoration being the gold oak sprigs on the lapels and gold taping on the sleeves. His court had always been sober, but when he defied the oracle the results were spectacular. The massive bookcases set at the back of the stage collapsed, showering the stage with their contents. Sicilia’s court and its culture suffered destruction.

There is no corresponding costume in the exhibition showing how Jeremy Irons was dressed for this scene in 1986. It was a production heavy with symbolism from the beginning. The stage featured a mirrored set, a chilly background in which onstage action was reflected: ice and snow. Leontes court was Regency, elegant and romantic, all in white. Costumes were both formal and softly beautiful with scarves, full sleeves and jewels. The mirrors, indicating a society in which people observed both themselves and others, subtly suggested the key to Irons’ suspicions. By the time the trial scene was reached his costume had grown into a massive cloak and head-dress that enveloped him, making him, like Tony Sher, impregnable.

The costume that we do have worn by Irons is a crushed velvet, deep blue tailed coat, of the same style worn earlier in the play. When we first saw Irons after the sixteen-year gap he was dressed in a hospital gown, confined to a wheelchair. Revived by the discovery of his lost daughter, he wore this blue coat to visit the statue of his dead wife. What were we to make of it? In style it was an echo of the earlier costume, but the softness of the coat, the deepness of the colour of the velvet, were in contrast to the hard brightness of the white version.

It signalled a change in Leontes, and kept eyes on him while creating a link to the costume worn by Hermione’s statue. Sher and Hicks’ costumes for this scene were less eye-catching, duller in colour, and allowed the focus of the scene to be the reawakening Hermione.

It signalled a change in Leontes, and kept eyes on him while creating a link to the costume worn by Hermione’s statue. Sher and Hicks’ costumes for this scene were less eye-catching, duller in colour, and allowed the focus of the scene to be the reawakening Hermione.

Into the Wild enables us not just to admire the skills of the costume-makers but to observe the way in which designers and directors have used costume to help the audience interpret The Winter’s Tale and its complex background, characters and relationships.

For more information, see the excellent full stage history of RSC productions of The Winter’s Tale 1948-1999 by Patricia E Tatspaugh in the Shakespeare at Stratford series published by The Arden Shakespeare in 2001.