A few days ago the death of the veteran Shakespeare academic Marvin Spevack was announced. For me his name is always associated with Concordances to Shakespeare’s works, both the one-volume Harvard Edition and the Complete and Systematic version in nine large volumes. There must be many people who have consulted this major work which, using the power of computing, gave a full statistical breakdown of the plays including what seemed at the time mind-boggling details not available elsewhere such as the number of lines spoken by each character. Dr Marga Munkelt has generously given me permission to reproduce her piece on his life and achievements, from which this is an extract:

A few days ago the death of the veteran Shakespeare academic Marvin Spevack was announced. For me his name is always associated with Concordances to Shakespeare’s works, both the one-volume Harvard Edition and the Complete and Systematic version in nine large volumes. There must be many people who have consulted this major work which, using the power of computing, gave a full statistical breakdown of the plays including what seemed at the time mind-boggling details not available elsewhere such as the number of lines spoken by each character. Dr Marga Munkelt has generously given me permission to reproduce her piece on his life and achievements, from which this is an extract:

Marvin Spevack was born in New York. After his undergraduate studies at the City College New York and Harvard University, he received his PhD from Harvard in 1953 with a doctoral dissertation on “The Dramatic Function of Shakespeare’s Puns.” He was a Fulbright Lecturer in Munich and Muenster (1961-63), before, in 1964, he became Professor of English Philology at the English Department of the University of Muenster.

When Professor Spevack came to Muenster, the project which made him internationally known was already on his mind: his pioneering computerized concordance to Shakespeare founded his reputation as one of the first (if not the first) scholar ever to utilize the computer for research in the humanities. Spevack’s nine-volume Complete and Systematic Concordance to the Works of Shakespeare (Hildesheim and New York, 1968-80) and soon after the one-volume Harvard Concordance to Shakespeare (Cambridge, MA, 1973) not only broke new ground for other computerized research in non-numerical disciplines but has also become, since then, a source and inspiration for electronic Shakespeare scholarship world-wide. Moreover, his Shakespeare Thesaurus (Hildesheim and New York, 1993) is the first in a row of similar attempts at classifying Shakespeare’s vocabulary.

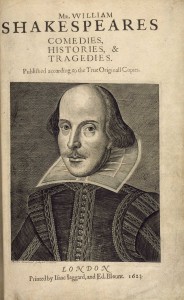

Before and after his retirement, Professor Spevack was a versatile, enthusiastic, and productive scholar. Among his substantial contributions to Shakespearean scholarship, the facsimiles of Shakespeare: The Second, Third and Fourth Folios (Cambridge, 1985), his New Variorum Edition of Antony and Cleopatra (New York, 1990), and his New Cambridge Edition of Julius Caesar (Cambridge, 1988; updated 2004) need to be singled out. Moreover, his enormous output of publications in other fields testifies to his range of interests as well as to his eloquence and beautiful prose. He wrote, for example, about communication and the new media as well as about ongoing changes in the current secondary education systems; he discussed subjects like dictionaries as well as aspects of book or library studies.

As a teacher, Marvin Spevack was a true “generalist”: in addition to teaching all fields of English literature, he also taught American drama, aspects of historical linguistics, and lexicography. Marvin Spevack was a dedicated, charismatic, and inspiring teacher who was deeply humane and outgoing; his openness for unorthodox topics—always based, however, on serious and sound research—was famous and his great sense of humor proverbial. He had the admirable ability to convey complicated matters in an understandable and accessible style. On the occasion of his sixtieth birthday he was honored by colleagues, friends, and students with a festschrift: Shakespeare–Text, Language, Criticism: Essays in Honor of Marvin Spevack, ed. Bernhard Fabian and Kurt Tetzeli von Rosador (Hildesheim, 1988).

Marvin Spevack’s last book combines his two foremost interests—Shakespeare and the Victorians—in A Shakespearean Constellation: J. O. Halliwell-Pillipps and Friends (forthcoming Muenster, 2013).

Marvin Spevack will be greatly missed and remembered for his brilliant teaching and scholarship as well as for his humanity and generosity.

If you would like to read the entire piece, go to SHAKSPER, The Global Electronic Shakespeare Conference, for many Shakespearian academics the place to go to for news on their subject. For over 20 years Professor Hardy M Cook, Professor Emeritus of Bowie State University, has run this site that brings together the Shakespeare academic community. Like Marvin Spevack, Hardy M Cook saw the potential of the Internet as a way of improving the supply of information and SHAKSPER is only one of the ways he has achieved this. Over the years it has gone through a number of different versions but is now a website open to all. Posts include requests for information, discussions, announcements of news, of upcoming conferences and of job vacancies. The site contains a searchable archive of past posts and a number of additional features including a list of scholarly resources on the internet and a page of teaching resources. Both these make the site much more than just a notice-board. Anyone may subscribe to receive regular updates by email and contributions are always welcomed.