A few weeks ago I wrote a post about Lionel Bradley, an ordinary man who lived through the second world war in London, recording his thoughts about not the blitz but the concerts which he and other Londoners attended: a bit of normality during a chaotic time. Just recently I’ve been watching a TV series, Wartime Farm, which has demonstrated how hard and drab life was for ordinary people during the war.

By 1945 people were both exhausted by war and hoping for victory. The Shakespeare Festivals inStratford-upon-Avonhad, remarkably, continued with barely a break, and audience figures were high, but with production values poor the theatre was taking a critical battering. It was clear to everyone that after the war things would have to change.

The first indication of the sort of change that was to happen came while the war was still on, in 1945. An injection of glamour was required, and the person chosen to signpost the way was American actress and dancer Claire Luce. She had appeared in several high profile movies with actors such as Humphrey Bogart and Spencer Tracy and on stage co-starred with Fred Astaire in The Gay Divorce, missing out on the film version (The Gay Divorcee) only because Ginger Rogers was already under contract. Luce had been in England for most of the war entertaining the troops. It had long been her ambition to work in Stratford-upon-Avon.

In Stratford Luce was given an extraordinary line of parts: Viola in Twelfth Night, Mistress Ford in The Merry Wives of Windsor, Beatrice in Much Ado About Nothing and Cleopatra in Antony and Cleopatra. She was playing not just the leading female role in each play but in several cases the highest-profile part, male or female. Antony and Cleopatra was chosen as the Birthday Play, and her Cleopatra was the most hotly-anticipated thing in the season.

She acquitted herself well in all the roles. Her Beatrice was described as “glittering”, and she was “superb and enchanting” as Viola. She presented “A Cleopatra whose feminine coils want no subtlety, and whose swift caprices have a natural and serpentine sinuosity”. The reviews agreed she was less effective in the final, tragic scenes of the play, but no matter: the Observer noted “It has been years since Nile has come so near to Avon”.

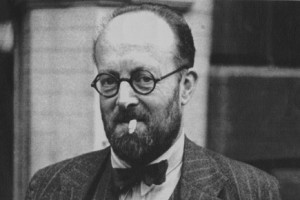

As well as recruiting a star to play leading roles, 1945 was also the year when the Memorial Theatre began to embrace the concept of image. The official photographs were usually taken by local photographers, but it was decided that they didn’t give a good enough impression of Luce’s performance. The photographer chosen for the reshoot was Angus McBean. McBean was becoming established as not just a major portrait photographer of society ladies but the photographer of choice for major theatrical stars like Laurence Olivier and Vivien Leigh. She was sent to him at his London studio, where he adapted the Cleopatra costume, wrapping her tightly in the glittering fabric in order to make it appear exotic and body-hugging, as well as echoing the figures in Egyptian tomb paintings.

The American journal LIFE published a feature on Claire Luce in Stratford, including a whole range of photos showing her in the olde worlde town. She is shown looking out of the window of the Shrieves’ House (claimed to be where she was staying), enjoying tea in a local teashop with one of her fellow-actors, visiting local landmarks and relaxing after her performance. Most of these photographs are new to me, and indicate just how special it was to have this star in town.

The American journal LIFE published a feature on Claire Luce in Stratford, including a whole range of photos showing her in the olde worlde town. She is shown looking out of the window of the Shrieves’ House (claimed to be where she was staying), enjoying tea in a local teashop with one of her fellow-actors, visiting local landmarks and relaxing after her performance. Most of these photographs are new to me, and indicate just how special it was to have this star in town.

You can see from the photograph of her as Cleopatra, taken by local photographer Tom Holte, why McBean’s portrait made such a difference.

Holte’s is undoubtedly truer to the performance, but McBean’s is a photograph of the Cleopatra the audience, starved of glamour and luxury, wanted to see. This one photograph marked the beginning of both McBean’s 17-year relationship with the Memorial Theatre and the improvement in the theatre’s national and international reputation.

These photographs were drawn to my attention by The Hamlet Weblog for 11 October 2012 in which Stuart Ian Burns mentioned these and other resources now available at the Google Cultural Institute.