The 21st May is the anniversary of the murder of Henry VI, according to Shakespeare committed by Richard Duke of Gloucester, later to be Richard III. And 22nd May is the anniversary of capture of Henry VI by the Yorkists.

These two events are both dramatised in Shakespeare’s play Henry VI Part 3, although six years came between them, the king being captured in 1465 and his death in 1471. Earlier in the play, Shakespeare gives Henry an almost hypnotic speech, full of repetition, in which he speaks of his longing for a simple life:

O god! methinks it were a happy life

To be no better than a homely swain;…

So many hours must I tend my flock;

So many hours must I take my rest;

So many hours must I contemplate;

So many hours must I sport myself;

So many days my ewes have been with young;

So many weeks ere the poor fools will ean;

So many years ere I shall shear the fleece…

Ah, what a life were this! How sweet! How lovely!

Gives not the hawthorn bush a sweeter shade

To shepherds looking on their silly sheep,

Than doth a rich embroider’d canopy

To kings that fear their subjects’ treachery?

When Richard comes to the Tower of London to murder Henry, the image of the shepherd and his sheep, with all its Christian associations, is used again:

So flies the reckless shepherd from the wolf;

So first the harmless sheep doth yield his fleece;

And next his throat unto the butcher’s knife.

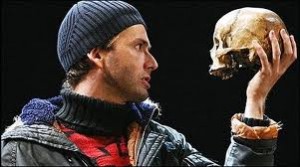

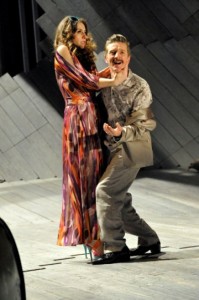

Shakespeare returned again to the death of Henry VI. There’s no gap between the end of Henry VI Part 3 and the start of Richard III, and Henry’s corpse is being accompanied by Lady Anne, the King’s daughter-in-law, to burial. Richard, who has killed not only the King but his son, Lady Anne’s husband, interrupts its journey. In an extraordinary moment, Lady Anne draws back the cloth covering the corpse, which bleeds in the presence of the murderer. This must have been seen by some in the audience as not much short of magic. Then in one of the strangest and most unlikely of scenes, Richard proceeds to woo Lady Anne while the corpse remains on stage.

The killing of Henry VI is much less well known than the murder of Richard II, depicted some years later in a masterful piece of writing. But the story of this gentle, ineffectual king and his violent death seems to have made a great impact on Shakespeare.

Henry’s lasting legacy was in the field of education: he founded Eton College and King’s College Cambridge. On the anniversary of his death an ancient ritual known as the Ceremony of the Lilies and the Roses is still observed: the Provosts of the two colleges and the Chaplain of the Tower of London lay flowers, lilies from Eton and roses from King’s, in the room where Henry was murdered.