On 7 April I was part of a panel on the subject of performance archives at the Shakespeare Association of America’s annual meeting in Boston. The panel was chaired by Michael Warren and the speakers were Kate Dorney from the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, Georgianna Ziegler from the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington, DC, and Tracy Davis from Northwestern University in Chicago.

My constribution was on digital developments in performance archives, and the following is the text of my presentation interspersed with the slides to which they relate. I’ve added a few links to relevant websites and online resources:

This session is entitled “The once and future performance archive” and while working with the Royal Shakespeare Company’s archives, one of the most important collections of material relating to Shakespeare in performance, I was involved in projects that involved digitising historic material, digital remastering, data projects and working with born-digital materials.

It’s worth remembering that digital projects have only been in existence for around 20 years, and many of the projects I’ve been involved with have felt experimental, sometimes having to wait for software to be developed to match the requirements of the project. Where once there seemed to be no signposts on the way, now guidelines for dealing with digital preservation are being published online by the UK’s Collections Trust.

It’s worth remembering that digital projects have only been in existence for around 20 years, and many of the projects I’ve been involved with have felt experimental, sometimes having to wait for software to be developed to match the requirements of the project. Where once there seemed to be no signposts on the way, now guidelines for dealing with digital preservation are being published online by the UK’s Collections Trust.

Many of the projects I worked on have been in partnership with other organisations, and it’s been important that information professionals who work with the collections are brought in from the start. They understand the organisation, preservation issues, and intellectual property concerns relating to the collection as well as knowing the kinds of demands made by users.

But following many years caring for a collection I’m now on the other side of the fence. Working independently and writing my own blog about Shakespeare, I’m as impatient as any of you with the restrictions imposed by collections to accessing and repurposing the material they care for. Before I look forward to where digital might be going, I’m going to briefly look back.

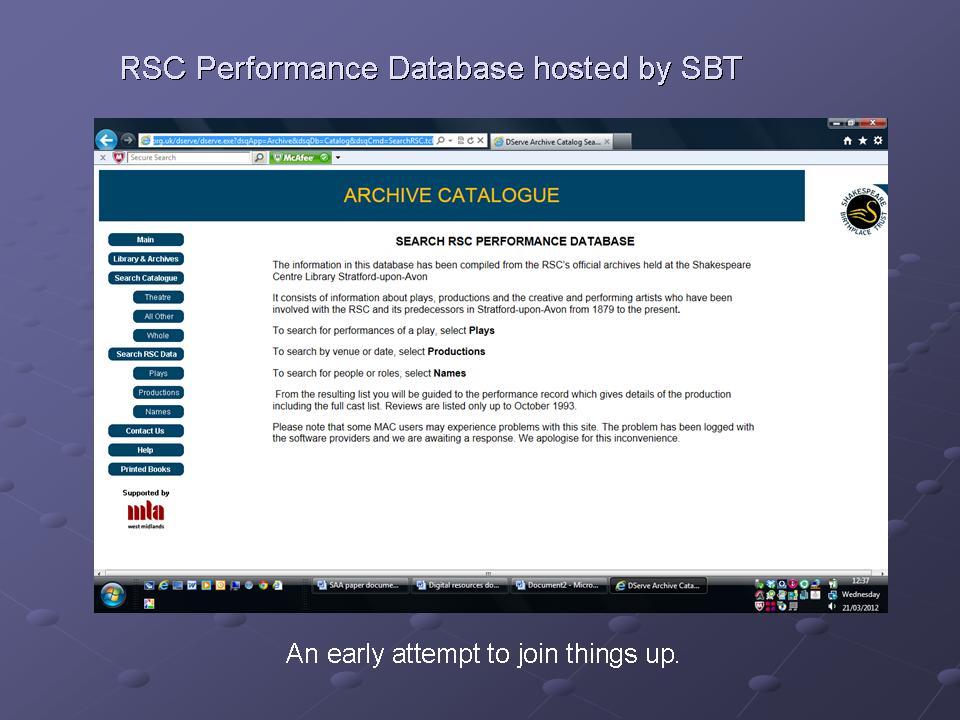

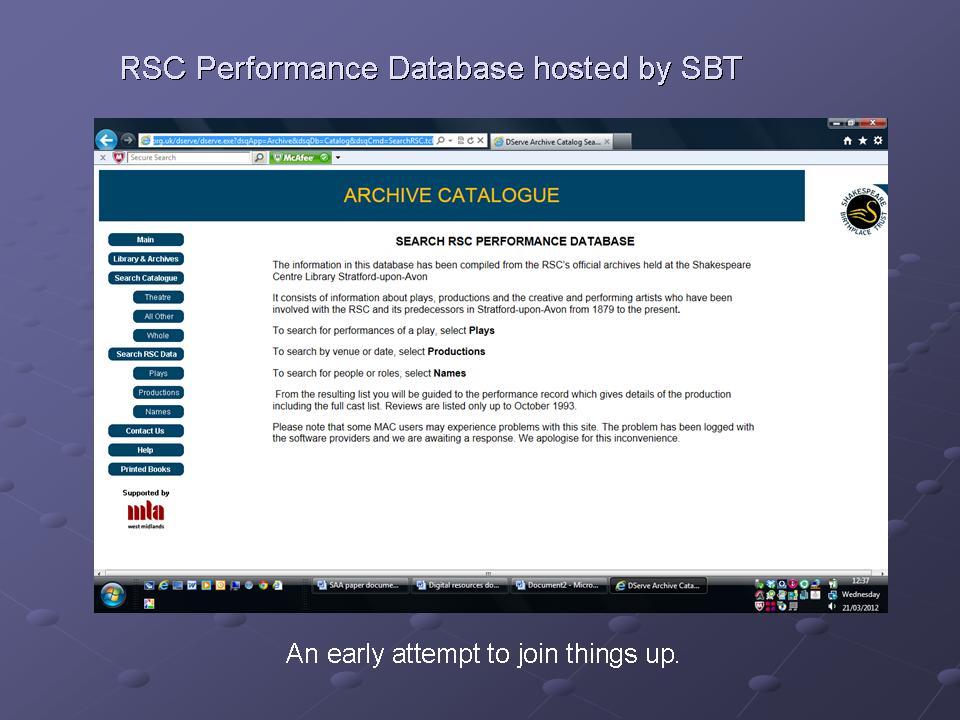

This is the RSC Performance Database, the largest digital project I was involved in. Unusually for a project hosted by a collection it doesn’t relate simply to its own holdings. It was, and remains, an attempt to convey hard factual information about over 130 years of RSC productions that can be used by anybody. It went live in 2004 after a painful 3 year gestation period during which the bespoke software was developed so that most, if not all, our requirements were met.

This is the RSC Performance Database, the largest digital project I was involved in. Unusually for a project hosted by a collection it doesn’t relate simply to its own holdings. It was, and remains, an attempt to convey hard factual information about over 130 years of RSC productions that can be used by anybody. It went live in 2004 after a painful 3 year gestation period during which the bespoke software was developed so that most, if not all, our requirements were met.

The structure of the database was developed in response to observation of how researchers worked, searching by person or play title, leading to a list of possible productions and then to a performance record that draws together all the facts relating to the production. From that record the database was designed to link through to the catalogue to display records of items. It’s a rigid structure that now seems out of date, but it remains a high-quality reference tool driven by user demand.

It has just been made public that a National Performance Data Project, using data from this and several other similar databases about UK performances, which is to be run by the Victoria and Albert Museum, is to be given funding. This database will enable people to search for information about a wide range of UK theatre productions.

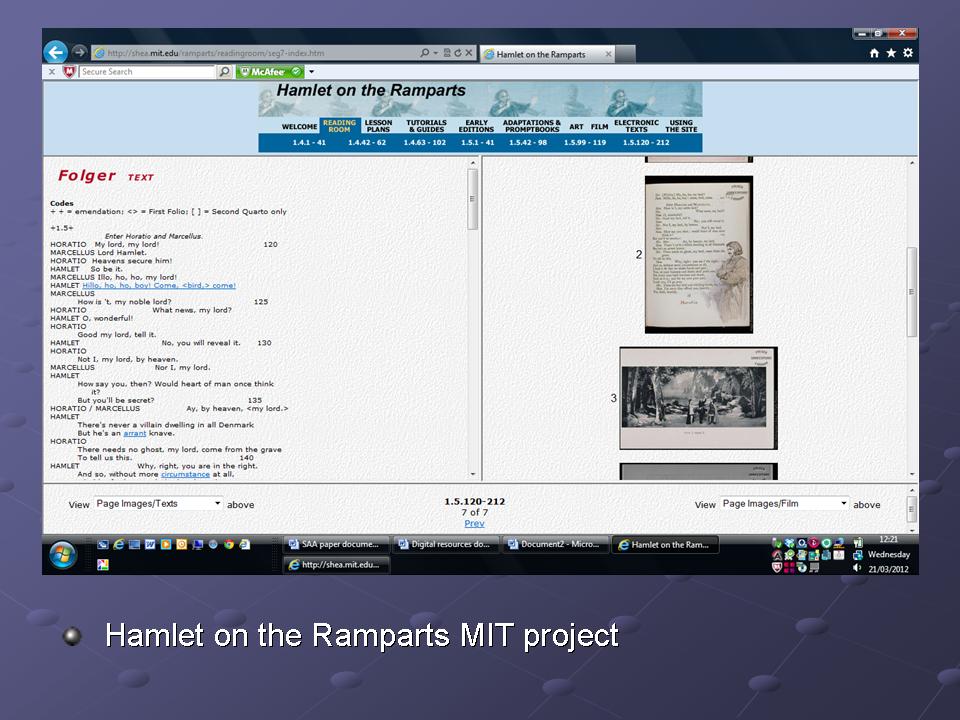

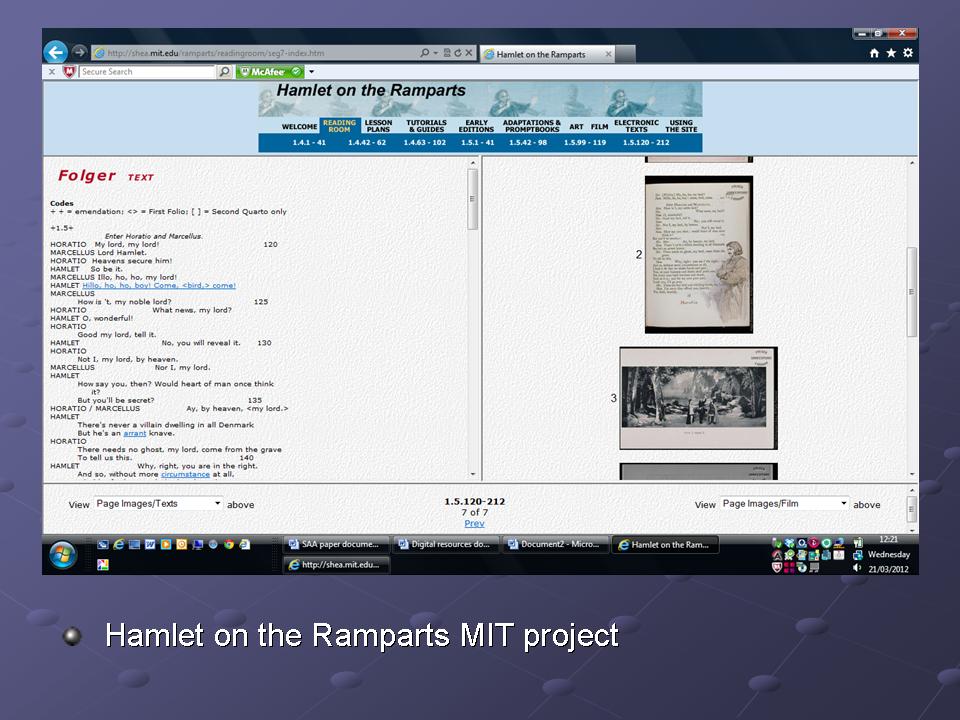

Hamlet on the Ramparts is another early digital project put together by MIT which brought together digitised material of various types from different collections, all relating to performances of Act1 Scene 4 and 5 of Hamlet. You can see that the designers struggled with the limitations of the software to deal with a variety of media, with different tabs for art and film for instance. It’s a project which tries to solve problems of finding linked data, but it doesn’t address the concerns of the curator.

Hamlet on the Ramparts is another early digital project put together by MIT which brought together digitised material of various types from different collections, all relating to performances of Act1 Scene 4 and 5 of Hamlet. You can see that the designers struggled with the limitations of the software to deal with a variety of media, with different tabs for art and film for instance. It’s a project which tries to solve problems of finding linked data, but it doesn’t address the concerns of the curator.

In her paper, Kate Dorney has already spoken about the work of the archivist. The digital world has amplified the challenges of caring for collections, with work in almost all areas of curation changing dramatically.

- Preserving and curating a collection: digital files might appear to be simpler to care for than paper or analogue ones, but long-term storage is actually more complicated and more costly.

- IPR: digital has increased demands for content and owners are aware of the potential value of their assets.

- Undigitised material: Users expect everything to be available online

- Sites like Google and Wikipedia present a challenge to professional standards and potential loss of control over content.

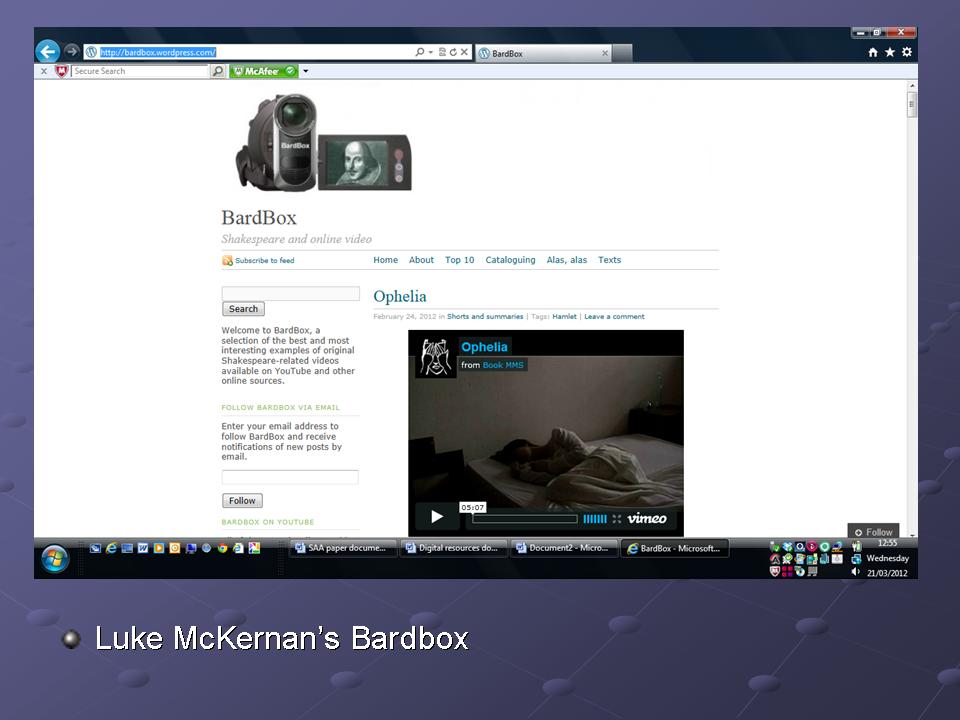

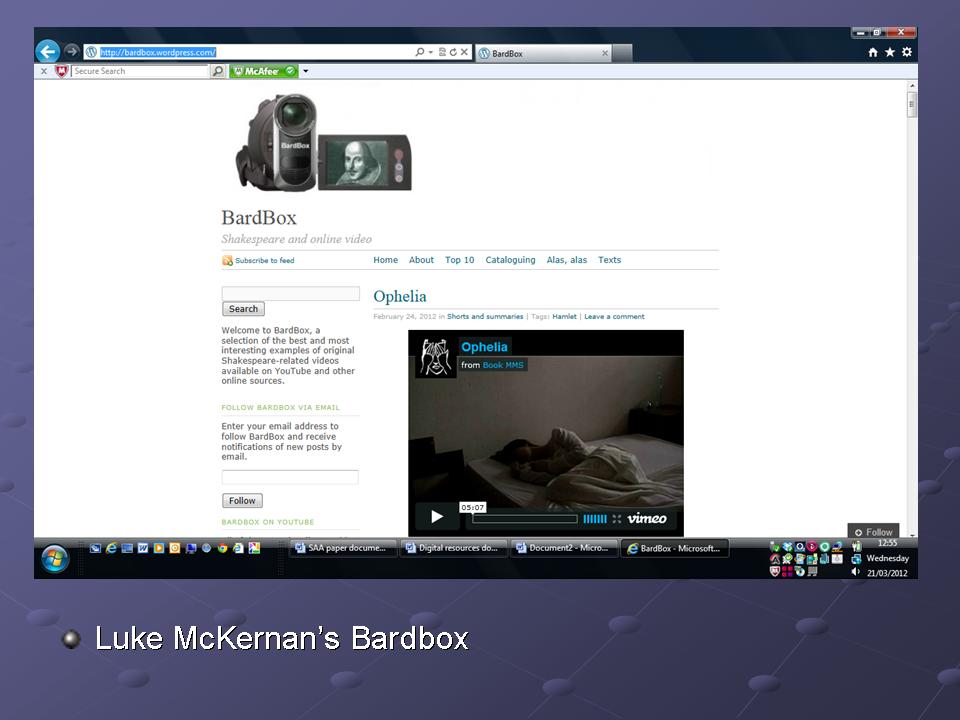

Bardbox is a personal and witty response from a professional curator at the British Library. Luke McKernan highlights the issues to Shakespeare material presented by the chaos of YouTube. He selects creative clips, helping users find the most interesting content, and catalogues them using consistent cataloguing rules. He even reminds users of the fugitive nature of digital content, documenting clips that are no longer available.

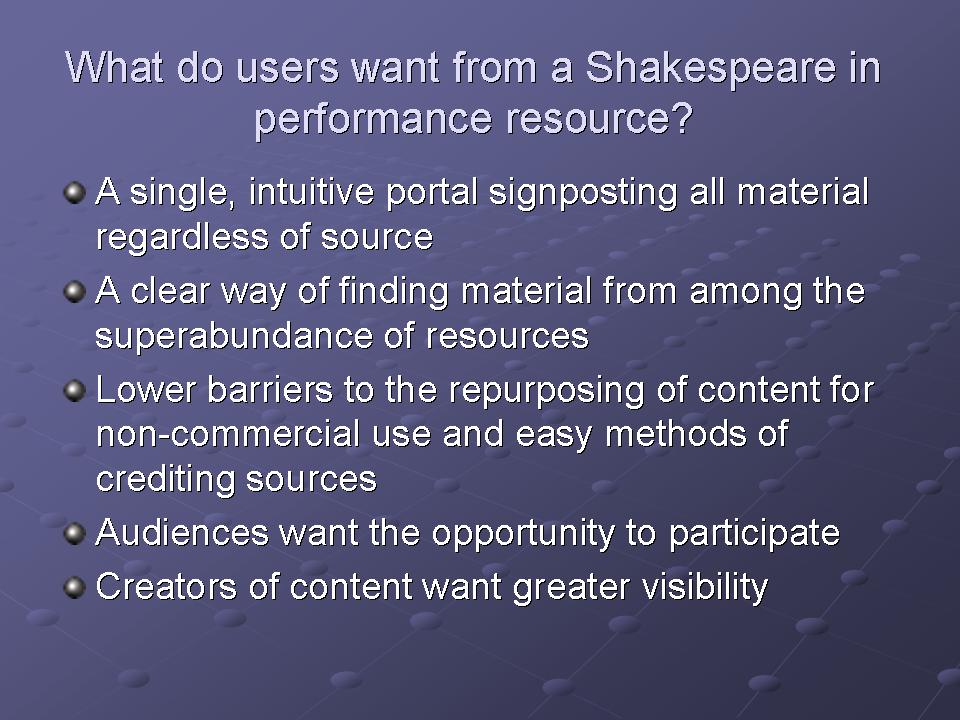

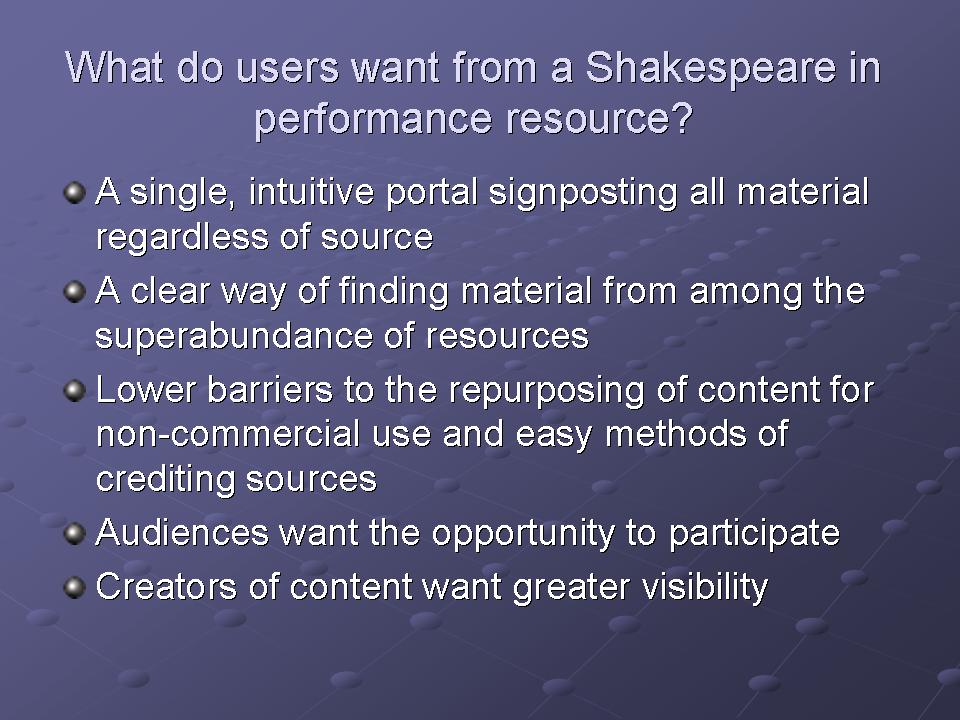

These are some of the things I think people want: a recent issue of Archives Quarterly published the results of a survey, which suggested that users of archives wanted a “more intuitive, more logical” resource, and the “consolidation of all resources into a single system”. They reported that there are “too many separate overlapping resources”.

These findings apply across every area of study, and would add that as well as not being able to find things, it’s not clear whether resources can be repurposed, or how to credit them. A lot of people want to participate, especially regarding performances they have enjoyed, and content creators want that content to be made as visible as possible. The same survey suggested a need for resources that reveal the hidden depth of archives to enable the creation of narratives and the development of new ideas.

How can technology resolve the gap between what curators do and what users want? A number of developments are offering new opportunities. Just in the last couple of weeks I’ve received information about several new projects which all aim to provide visual interfaces to massive amounts of data which will allow for more intuitive searching and the ability to organise information from many different sources, regardless of format.

ChronoZoom aims to “imbed multimedia that will tell the history of everything”, while Histopedia seems to have slightly more modest aims. Both are examples of the new tools that are being developed all the time.

Social media has allowed many more people to comment on and use collections – there’s a real thirst for the material which collections own. Now professionals working within organisations are joining in with social media with institutional blogs, facebook pages and twitter feeds.

And both the British Museum and the John Rylands University Library in Manchester are appointing Wikipedia librarians to add content about their collections to this site which most universities have been trying to steer their students away from up to now.

Technology is allowing for greater democratisation of learning and knowledge, encouraging openness and communication. These ideals are also shared by libraries and archives: what prevents them from joining in more fully is their need to limit access for reasons usually beyond their control.

With digital technology now moving in a positive direction, I suggest that Shakespeare in performance is a perfect subject around which to create a project to link up existing digital resources and to create new ones, and it’s a subject which could and should involve archivists, academics, students and the public working together.

Shakespeare is performed around the globe and appeals at many levels. It’s a cross-disciplinary subject, and looks both backwards and forwards in time, allowing for a constantly evolving project. It would be highly participative, offer a future for all kinds of content, be visual and improve the image of archives.

This project, Shakespeare’s Global Communities, is still in the design stages. Controlled by the Shakespeare Institute it will create new resources based on academic and public responses to the 2012 World Shakespeare Festival performances. It will have a geographical visual interface, and each production will have its own page to which the responses will link. It should offer some ideas about how a more inclusive project might work.

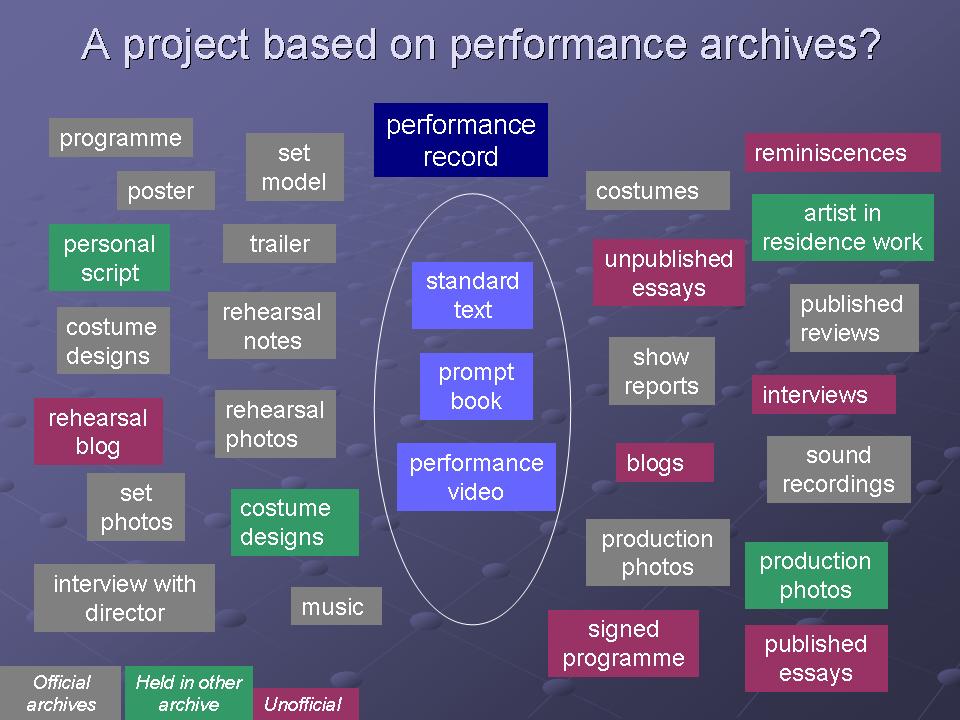

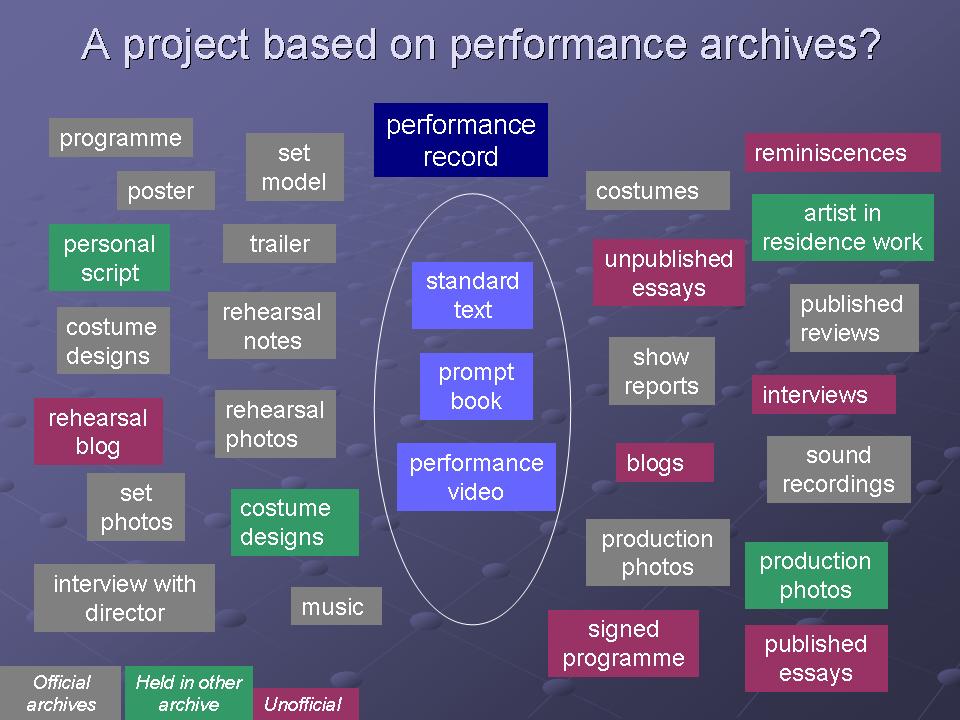

This diagram is a simple attempt to explain how a performance archive project could work. It links a performance record to the texts and video – linear versions of the production – and then to digital files in the official archive such as photographs and rehearsal notes, files from other archives such as an actor’s personal script, and unofficial files added by individual such as essays or own reminiscences. Speaking to an audience like the Shakespeare Association of America, full of people who have attended multiple productions of Shakespeare, I’m struck by the fact that as academics you already have huge amounts of data which you could contribute, with your conference papers, personal journals and memories. Curators and academics inevitably see things from different points of view, but with a university-led project like Shakespeare’s Global Communities, which has such obvious application to performance archives, there is an opportunity for them to work together to create something that is more than just another of those separate resources.

I’d be delighted to receive feedback on this presentation and look forward to hearing from you.

I’d be delighted to receive feedback on this presentation and look forward to hearing from you.

![STC 7271, fol. [Aai] verso- Aaii recto](https://theshakespeareblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/04/Christine-de-Pisan-300x230.jpg)