A new play about the great man of the theatre Harley Granville Barker is now playing at the Hampstead Theatre, London. As explained on the Radio 4 Today programme on 29 February Granville Barker virtually invented the idea of the director, and is one of the most influential people in theatre from the last 150 years. He campaigned for the National Theatre, decades before it became a reality, hoping it would raise standards within the profession.

A new play about the great man of the theatre Harley Granville Barker is now playing at the Hampstead Theatre, London. As explained on the Radio 4 Today programme on 29 February Granville Barker virtually invented the idea of the director, and is one of the most influential people in theatre from the last 150 years. He campaigned for the National Theatre, decades before it became a reality, hoping it would raise standards within the profession.

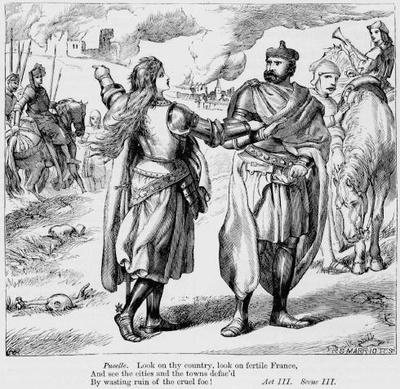

As well as being a famous director he was also an actor, author, playwright and activist. He produced three groundbreaking seasons of plays at the Royal Court from 1904-1907 and his most famous work, productions of Shakespeare’s The Winter’s Tale, Twelfth Night and A Midsummer Night’s Dream were put on at the Savoy Theatre in London from 1912-1914. These productions caused a sensation. Instead of complicated realistic sets which slowed the action of the play down every time a change was required he used simple sets, unfussy costumes, brightly-painted curtains and an apron stage. He restored fuller texts and insisted on a speedy, natural delivery of lines. Today this may not sound revolutionary, but he was reacting against the traditions of spectacular productions with an over-dependence on elaborate sets.

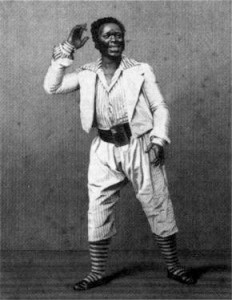

His production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream was perhaps the most influential, with a small cast, spare staging and golden, slightly sinister fairies based on Asian idols. Here we see George Burrows as Oberon and Donald Calthrop as Puck.

The current play, Farewell to the Theatre, is written by Richard Nelson, and focuses on the period after this major theatre work. He took some of the plays to the USA and there fell in love with an American authoress. He divorced his first wife, the famous actress Lillah MacCarthy, and during the 1920s he moved to Paris. For the rest of his life he turned his back on the theatre, which he had done so much to shape, and concentrated on writing.

His influence is still felt today through his series of Prefaces to Shakespeare, which examine the plays in minute detail. He wrote in the introduction “The text of a play is a score waiting performance, and the performance and its preparation are… a work of collaboration…. A producer might talk to his company…on such such lines as these Prefaces pursue, giving a considered opinion of the play, drawing a picture of it in action, providing, in fact, a hypothesis”. The plays discussed include Hamlet, Antony and Cleopatra, Cymbeline, Romeo and Juliet, Othello and Love’s Labour’s Lost among others.

Actor and writer Simon Callow comments: ‘Barker offers a learned yet deeply intuitive approach to Shakespeare as a man-of-the-theatre, an act of empathy so complete as to give the illusion that Shakespeare himself has been given the opportunity to say what he was aiming for’.

To find out more about this complex and enigmatic man, see the play which is on at the Hampstead Theatre until 7 April.