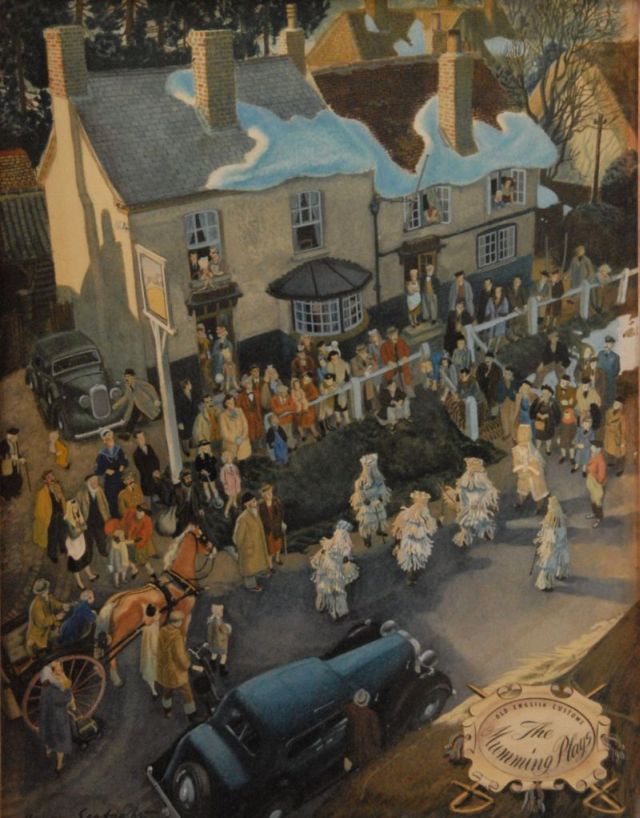

You’re at work again and everything is getting back to normal. Spare a thought then for those who are busiest at Christmas – those who entertain us. In spite of the more sophisticated offerings available today, people still enjoy pantomimes. These are often the only live theatre people ever attend and a throwback to the old tradition of live performance at Christmas, encouraged by a combination of long dark evenings and the temporary shut-down of most outdoor activities. In summer, Shakespeare suggests, “the human mortals want their winter cheer”.

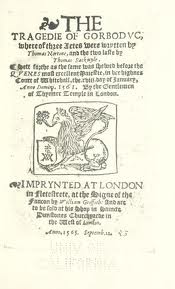

For Shakespeare and his company the Christmas season was particularly busy. I’ve just been reading Alvin Kernan’s book Shakespeare, the King’s Playwright, which brings together much of what’s known about these performances. Companies played before Queen Elizabeth on 32 occasions in the last 10 years of her reign, but in the first 10 years of James’ reign there were 138 performances, and rather than ending at Epiphany, 6 January, the period was gradually extended.

Within only a few weeks of arriving in London King James 1 issued a royal warrant setting up his own official players, The King’s Men, previously The Lord Chamberlain’s Men, “as well for the recreation of our lovinge subjectes, as for our Solace and pleasure when wee shall thingke good to see them, during our pleasure”.

The King’s Men couldn’t satisfy all the needs of the court, but they performed more than any other and as their resident playwright, Shakespeare supplied many of the plays. In any year Shakespeare probably only ever wrote two new plays, so older plays would have been brought back into the repertoire for performing at court. It’s probable that all of Shakespeare’s plays were performed before the King at least once. To celebrate the marriage of James’ daughter Elizabeth’s marriage, 20 plays were performed in the season 1612-13, including Much Ado About Nothing, The Tempest, The Winter’s Tale, Othello and Julius Caesar.

The records don’t often give the details of exactly which plays were performed, but it is known that Measure for Measure was given on St Stephen’s Day (26 December) 1604, and King Lear on the same day in 1606. St Stephen’s Day signalled the start of the playing season, and was a day dedicated to charitable giving to the poor. The revelling came later. Preparations for court performances by professional companies would have taken weeks, and new plays would have had several public performances like modern previews at the Globe before being shown to the king.

Alvin Kernan explains how this would have affected the author:

Shakespeare may have originally produced his plays on the public stage, but he would have to have been remarkably dull – which he surely was not – not to have remembered after 1603 that his new plays would at Christmastime be acted before the king and his court…Even had he wished to avoid politics, Shakespeare was forced to become a political playwright.

A courtier, Dudley Carleton, wrote to his friend John Chamberlain during January 1604:

We have had here a very merry Christmas and nothing to disquiet us save brabbles amongst our ambassadors, and one or two poor companions that died of the plague. The first holy days we had every night a public play in the great hall, at which the king was ever present and liked or disliked as he saw cause, but it seems he takes an extraordinary pleasure in them. The queen and prince were more the players’ friends, for on other nights they had them privately and have since taken them to their protection.

On New Year’s night we had a play of Robin Goodfellow and a mask brought in by a magician of China. There was a heaven built at the lower end of the hall out of which our magician came down…

The Sunday following was the great day of the Queen’s mask. The hall was much lessened by the works that were in it…and …[they] placed…loose mantles and petticoats,…embroidered satins and cloth of gold and silver, for the which they were beholden to Queen Elizabeth’s wardrobe…So ended that night’s sport with the end of our Christmas gambols.

Shakespeare dramatised performances at court in several of his plays. The raiding of the old queen’s wardrobe for fancy costumes sounds disconcertingly like the ad hoc set-up for the amateurs in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, but the courtiers themselves probably took part in this masque, the finale of the celebrations after which the day came for them, like us, to get back to our usual routine.