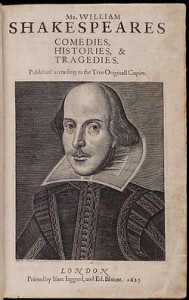

An exhibition on the subject of suicide doesn’t sound very suitable for the festive season, but George Chakravarthi’s Thirteen, currently at the Royal Shakespeare Theatre in Stratford-upon-Avon, is no ordinary exhibition.

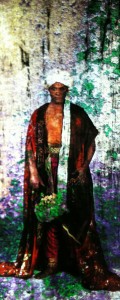

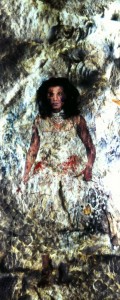

The artist became interested in how the perception of suicide has changed in our post-9/11 world, and can be motivated by a moral or ideological cause. The exhibition features photographs of Chakravarthi himself assuming the role of thirteen of Shakespeare’s most doomed characters. He often uses himself as a model for his work to explore ideas of identity, race and sexuality.

The images are strongly dramatic: he dressed himself in costumes from the RSC then added layers of detail: “I tried to avoid being too theatrical because the theatre is in the costume, the visual texture and the colour”. The photographs were printed onto a transparent material, mounted on Perspex and placed on a sheet of LED lighting. The end results are complex pictures, rich in symbolism, that seem to glow. In the old Picture Gallery, the architecture reminiscent of a church, the connection with religious imagery on stained glass is unmistakeable.

Rather than focusing on death, Chakravarthi has said that he’s interested in the immortality of Shakespeare’s characters, which is why Cleopatra, one of the most iconic of them, is the most striking and complex of the images. The booklet accompanying the exhibition states “It is the glamour attendant on these deaths, however dreadful, which transforms them into icons of beauty, terror, nobility and tragedy”.

Some of the images are disturbing, especially the androgynous Lady Macbeth and Timon, portrayed upside down, seeming to turn back into dark earth. In the plays the suicides are motivated by honour, guilt, grief, hopelessness or loss.

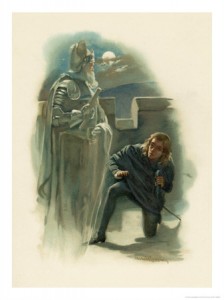

Romeo and Juliet face each other across the gallery, matching each other in colour and style. They’re the ones among the thirteen whose death seems most pointless, but who positively embrace death rather than live a life without love. This quotation from Romeo and Juliet is reproduced in the booklet that goes with the exhibition:

Here, here will I remain

With worms that are thy chamber-maids; O, here

Will I set up my everlasting rest,

And shake the yoke of inauspicious stars

From this world-wearied flesh. Eyes, look your last!

Arms, take your last embrace! and, lips, O you

The doors of breath, seal with a righteous kiss

A dateless bargain to engrossing death!

These beautiful, exotic and strange images are on display until April, and if you’re in Stratford-upon-Avon do go and visit them. Before you do, or if you’re not able to see them in person, take a look at the RSC’s website for an interview with George Chakravarthi and a guided tour by him which gives lots of detail about the portraits. They are a bewitching response, in his words “a memorial…a temple” to some of Shakespeare’s most compelling characters.

I must point out that the images on this page were taken by myself solely for this post and do not fully represent the exhibits. To see them properly illustrated use the link above to the RSC’s website – or go and see them yourself.