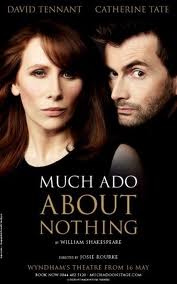

I don’t think I’ve ever seen an actor having more fun onstage than I did on Monday night when I went to Much Ado About Nothing at Wyndham’s Theatre London. From his first entrance in a ridiculous golf buggy right through to the curtain call where he bounds across the stage you know David Tennant is just loving it.

I don’t think I’ve ever seen an actor having more fun onstage than I did on Monday night when I went to Much Ado About Nothing at Wyndham’s Theatre London. From his first entrance in a ridiculous golf buggy right through to the curtain call where he bounds across the stage you know David Tennant is just loving it.

The part of Benedick is a gift to any comic actor, but that isn’t to say it’s all comedy. Tennant clearly loves all the dressing up (his costume for the ball scene is outrageous), the physical comedy of the gulling scene and those speeches directed straight at the audience, but there are serious moments too, and he and Catherine Tate manage to control that chilling moment when Beatrice demands Benedick should “Kill Claudio” without a titter from the audience.

Tennant’s theatre credentials are impressive. In his first season for the RSC, 1996, he combined one of Shakespeare’s challenging fools, Touchstone in As You Like It, with slimy Jack Lane in The Herbal Bed and a straight down the line Colonel Hamilton in The General From America. On his next visit, in 2000, he played Jack Absolute in The Rivals, Romeo in Romeo and Juliet, and Antipholus of Syracuse in The Comedy of Errors. In 2008, though, his ability to communicate with a live theatre audience was developed to the full with his Hamlet and Berowne in Love’s Labour’s Lost, which even then felt like a warm-up for Benedick. He’s performed important roles with many other theatre companies too.

In between and since, he’s managed to balance his stage career with serious dramatic roles on TV and film and the sci-fi fantasy of Dr Who. In a recent interview with Simon Hattenstone he made it clear how much he enjoys this blend of live theatre and studio work.

When Josie Rourke began directing the production she couldn’t have known how timely this exuberant production would turn out to be. In her programme essay, Emma Smith writes about the period when the play was first performed:

“For London audiences in 1598-99, conscious of ongoing conflicts in Ireland and in the Low Countries, beleaguered by high food prices, suppressing political uncertainties about the end of the ageing Elizabeth’s reign, the play must have seemed an escapist fantasy”

With 2011’s ongoing conflicts in Afghanistan and Libya, high food prices and riots in the streets of our cities, we’re all again in need of the feel-good factor.

George Bernard Shaw described Much Ado About Nothing as “romantic nonsense”, and you could certainly drive a bus through the holes in the plot of the play. It’s as if Shakespeare was so enjoying writing the scenes that sparkle with wit and repartee he couldn’t quite be bothered with the tedious business of tidying it all up. Rourke manages to give the Claudius and Hero story some weight by adding a nightmare sequence where Claudio threatens suicide in remorse for Hero’s death until prevented by a vision of Hero. Is this letting Claudio out of jail free or just filling in one of those gaps?

Beatrice can be seen as a woman whose prickliness covers her vulnerability, her gulling leaving her painfully exposed. But Catherine Tate grasps the opportunity for physical comedy with a hilarious aerial turn. Rather than worry about any dark psychological examination, the audience can just surrender to the production’s good nature. As Tom Stoppard writes in Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead, “I mean, people want to be entertained “.

Beatrice can be seen as a woman whose prickliness covers her vulnerability, her gulling leaving her painfully exposed. But Catherine Tate grasps the opportunity for physical comedy with a hilarious aerial turn. Rather than worry about any dark psychological examination, the audience can just surrender to the production’s good nature. As Tom Stoppard writes in Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead, “I mean, people want to be entertained “.

The evening, though, belongs to Tennant, energy and enthusiasm bursting from every pore. And if this play, above all others, didn’t delight, it’s would be an opportunity missed. As it is, the audience is allowed to leave having experienced what Emma Smith calls “the fleeting, soap-bubble evanescence of the theatrical moment”.

Catch it if you can before September 3.