When I put up my list of top ten Shakespeare speeches I promised a second set of speeches which I associate with a particular performance.

My list provided a great subject for discussion during a long walk when my husband reminded me of some of the great actors I’ve missed out, including Michael Pennington, David Tennant, Tony Sher, Patrick Stewart, Harriet Walter, John Woodvine, Penny Downie, Ian McKellen. I’ve been lucky enough to see and hear many brilliant performances on stage – I might have to do a third list!

If you want to read the whole speech there’s a link to the scene, taken from MIT’s online text. Only one is available to listen to online, but see the end for advice if you would like to listen to recordings of the performances.

1. Hamlet, Act 2 Scene 2, Simon Russell Beale

What a piece of work is a man!

I mentioned this one in my earlier post. The speech is often performed out of context but Beale performed it stunningly as part of the play for the National Theatre. This is a studio recording of a different speech but gives a flavour of Beale’s performance.

2. Richard II, Act 1 Scene 3, David Suchet

O, who can hold a fire in his hand

I vividly remember this speech from the 1980 RST production in which David Suchet played Bolingbroke. It is specifically about the pain of banishment, but speaks of any kind of separation or loss.

3. Henry VIII, Act 2 Scene 4, Jane Lapotaire

Sir, I desire you do me right and justice

Jane Lapotaire’s controlled anguish as the Queen was wonderful in the RSC’s 1996 Swan Theatre production. The speech is on The Essential Shakespeare live Encore 4.

4. A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Act 2 Scene 1, John Carlisle

I know a bank whereon the wild thyme blows

One of Shakespeare’s most famous speeches, quite rightly. John Carlisle has a wonderfully rich and poetic voice perfectly suited to this sumptuous speech, performed at the Royal Shakespeare Theatre in 1989.

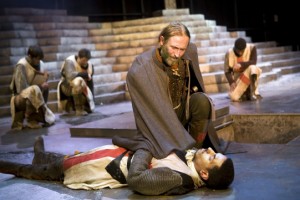

5. Coriolanus, Act 3 Scene 3, Alan Howard

Alan Howard made this part his own, playing it for the RSC in Stratford, London and on European tour in 1977-78 before recording it for the BBC’s TV production. His performance is too big for the small screen, but it’s a good recording of this definitive performance.

6. Richard II, Act 5 Scene 5, John Heffernan

I have been studying how I may compare

John Heffernan played the title role at Bristol’s Tobacco Factory in 2011. The intimate stage with the audience on all sides left the actor vulnerably alone on stage to deliver this final soliloquy.

7. The Tempest, Act 5 Scene 1, Derek Jacobi

Ye elves of hills, brooks, standing lakes and groves

The actor, playing Prospero in 1982 used nothing but the power of his voice to dominate the huge space of the RST, starting quietly and building to a crescendo. On The Essential Shakespeare live.

8. A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Act 2 Scene 1, Juliet Stevenson

These are the forgeries of jealousy

Juliet Stevenson’s wonderfully lyrical voice was perfect when she played Titania for the RSC in 1981.

9. Cymbeline, Act 2 Scene 2, Anton Lesser

The presence of Anton Lesser on any cast list is always a guarantee of quality. Here he plays the villain of the play, Iachimo, for the RSC’s production at the Swan Theatre in 2003. In this night-time scene he spies on the heroine while she sleeps. On The Essential Shakespeare live Encore

10. The Comedy of Errors, Act 2 Scene 1, Judi Dench

His company must do his minions grace

Judi Dench gave a perfectly judged performance as Adriana for the RSC in 1976. In this scene she was a figure of both comedy and tragedy as she spoke of losing the love of her husband. The scene on YouTube is from the TV recording – not the same speech but similar enough to give the idea.

Notes on availability:

RSC performances from 1982 are available to view on video at the Shakespeare Centre Library and Archive, and the National Theatre’s Hamlet should be available at the National Theatre’s archives. Three recordings are on the RSC’s CDs The Essential Shakespeare live and The Essential Shakespeare live Encore, selections made from the recordings at the British Library’s Sound Archive, where they can be listened to.

There are lots of great recordings on YouTube. I specially recommend the South Bank Special – Word of Mouth, a masterclass in speaking Shakespeare’s verse with John Barton, Trevor Nunn and Terry Hands.