The one-man play Being Shakespeare is just reaching the end of its run at the Trafalgar Studios. It’s a real tour de force by distinguished actor Simon Callow who switches effortlessly from narrative to speeches from Shakespeare’s plays, bringing characters as diverse as Juliet and Falstaff to life.

The play, written by Shakespeare academic Jonathan Bate traces Shakespeare’s life by following the Seven Ages of Man speech from As You Like It. One of the seven ages is the soldier,

Full of strange oaths, and bearded like the pard,

Jealous in honour, sudden and quick in quarrel,

Seeking the bubble reputation

Even in the canon’s mouth.

The play examines the possibility that Shakespeare spent some time as a soldier during the so-called lost years between the birth of his twins in Stratford and his appearance in London as a budding playwright around eight years later.

Shakespeare does indeed make frequent references to battles, armies, and weapons, painting vivid pictures in words of scenes of military life including the recruitment of would-be soldiers. In Henry IV Part 1 Sir John Falstaff describes the soldiers he has recruited, “discarded unjust serving-men, younger sons to younger brothers, revolted tapsters and ostlers trade-fallen, … and such have I, to fill up the rooms of them that have bought out their services”.

In the follow-up play, Henry IV Part 2, he dramatises the actual process by which men were put on the muster roll. Four men are needed, but the two likeliest ones buy their way out leaving the “scarecrows” appropriately named Shadow, Feeble and Wart.

Among the Stratford Corporation’s Miscellaneous Documents at the Shakespeare Centre Library and Archive is a single page dating from 1588, in the middle of Shakespeare’s lost years and the year when the country was in turmoil because of the threat of invasion by the Spanish Armada.

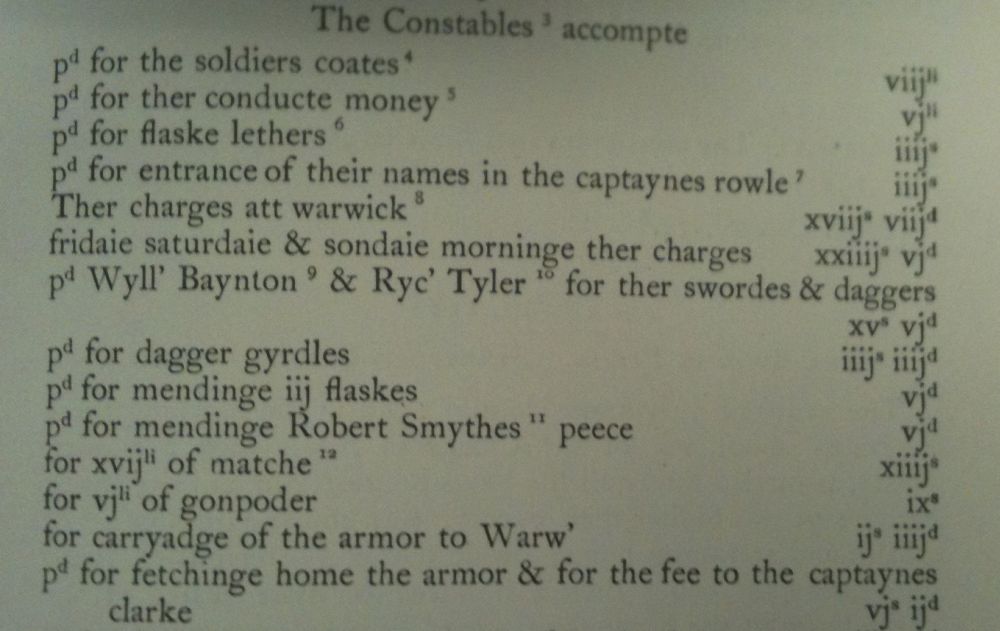

The document (BRU15/12/34) is the Constable’s Account demonstrating how much was spent in Stratford in fitting out the recruits to the militia. In it we find that the total of £23 18s 0d was spent on items like coats, dagger girdles and gunpowder. On this occasion the general muster took place in Stratford instead of the county town, Warwick. The event is described in Edgar Fripp’s posthumously published book Shakespeare, Man and Artist, as “an imposing affair, attended by leading magistrates, bailiffs of neighbouring towns, officers of various ranks, and a special preacher. Wine flowed freely, with the customary sugar (as costly as the wine) and minimum of bread”.

Was this the occasion that Shakespeare was remembering when he wrote the scenes in the two parts of Henry IV? Even if he wasn’t there on this occasion he would have been aware of how the mustering system worked. The town had provided soldiers earlier in Shakespeare’s lifetime, in both 1569 and 1577, and the town armoury was kept next to the school which Shakespeare would have been attending. In The Taming of the Shrew, Petruchio appears with “an old rusty sword ta’en out of the town armory, with a broken hilt”.

To my mind, these scenes aren’t written from the point of view of the recruits, all of whom are simple uneducated men. It’s implied that anyone bright enough would have managed to get out of being recruited, and Shakespeare was certainly smart enough to talk his way out of this tricky situation.

The argument that William of Stratford was mustered but talked his way out of service is implausible. First, as a 23-year-old male he would be a prime candidate for recruitment. Second, the Anglo-Spanish war of 1585-1604 had been gathering momentum, and the Armada posed a clear danger to England. The armies of Spain and other Continental forces threatened to come ashore and do great harm. As a result, all available men were being mustered. It would have been hard for anyone to talk his way out of service. Third, not all soldiers were uneducated. Look at the English nobility who served, e.g., Sir Thomas Lucy and Sir Thomas North. Lucy organized the Stratford muster. Would he likely give William a free pass? What reason is there to think so? Fourth, it is overlooked that William wanted to get out of Stratford, an option presented by being in the militia. Fifth, you ignore the possibility that he was brave and patriotic and wanted to defend his country. Sixth, as you know, his works teem with military terms, knowledge and data. If there ever was an exercise in conjecture, the proposal that we should reject Shakespeare’s military contribution on the grounds that he was educated and talked his way out of it is a classic. Ivor Brown, an expert on Shakespeare, said in his highly regarded treatise that Shakespeare was pulled out of the Stratford Grammar School prematurely. How much “education” are you implying he had? Look at the play King Henry V. Don’t the soldiers (Fluellen) know about the discipline and rules of war? Not all the soldiers were ignorant. Think about it.